This week has seen me travelling to Vienna and Bratislava for a meeting of the European Research Council’s Scientific Council. Travelling between the two cities along the Danube by fast boat provided a rare treat of a little relaxation fitted into the normally intense work of such a committee meeting. I am still learning the ropes, getting to grips with acronyms (of course) and structures; this was only my second formal meeting of the Council and the ways of Brussels can seem a little mysterious to newcomers. I also attended my first meeting of the Gender Working Group, a group chaired by fellow Council member Isabelle Vernos, who contributed to the recent Nature Special focussing on gender. In her article there she included some ERC statistics and put the case against quotas. There is absolutely no doubt that the ERC takes the issue of gender very seriously and it worries about the statistics surrounding the success rates for women in the various rounds of awards. The figures are not good, as their 2012 Annual Report makes clear. (see data below) Yet the reasons for this are many and complex – and to some extent still unknown. The good news is that the figures are being collated and analysed. The bad news is that there is no simple fix.

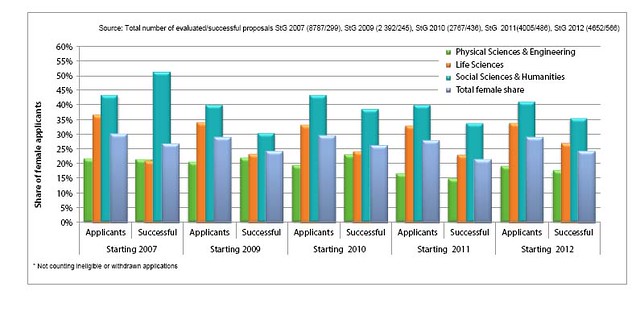

Comparative figures for total applicatons and successful applications from women across the 3 domains and for all calls of ERC Starting grants.

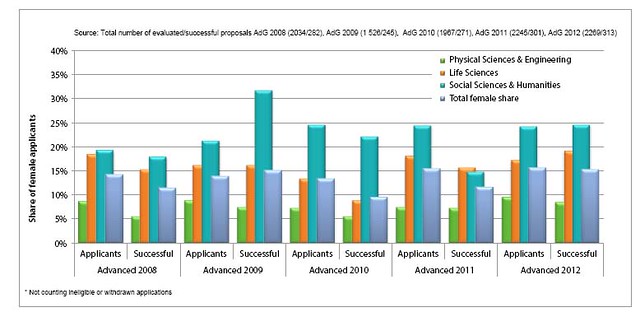

Comparative figures for total applicatons and successful applications from women across the 3 domains and for all calls of ERC Advanced grants.

If the figures above (taken from the 2012 annual report) are examined closely there are some intriguing factors. Speaking as a physicist, it is heartening to see that the PE domain (i.e. the Physical and Engineering Sciences) show success rates – particularly for Starting Grants, less so for Advanced Grants – which are pretty much the same for women and men, year on year (Social Sciences and Humanities also don’t too badly on this front). This is very much not the case for the LS (Life Sciences) domain. So are the eligible women in the life sciences weaker on average, are the panels more prejudiced or is there something in the way LS proposals are written that disadvantages women? The statistics alone are not enough to identify the problems, and there was much debate about this.

One of the figures that isn’t present in the annual report concerns the make-up of panels. The ERC is determined to get good representation of women on panels, but this should not simplistically be thought to be because having more women on panels will mean women will be treated more favourably. Indeed the statistics we were shown this week demonstrate clearly that there is no correlation between success rates for women and make-up of panel and I am glad to hear it myself: favourable judging by women of women would hardly be healthy and the broader evidence is that unconscious bias against women is as prevalent amongst women as men. But women should be at the table so that their voices are heard, judging both men and women. This, by now, should just be taken as read. Furthermore, although it is hard to find non-emotive words to describe this, if panels are seen as a power-base and if membership of panels is regarded (as it is) as a figure of merit, of course women should be participating in them. It is sad that this still needs to be discussed but, as with conference speakers, it remains the case that it is all too easy for women to be overlooked or forgotten. It is good that the ERC are very sensitive to the matter, so that oversight cannot accidentally occur.

So, to return to success rates. In the course of informal discussions the following points were made, which are purely supposition and may even be thought to include some unwelcome stereotyping. Nevertheless, they are probably thoughts worth exploring further if the causes – and solutions – of the lower success rates of women are to be appropriately dealt with.

- Maybe women do better (comparatively) in the PE domain because, those who have survived to the level of seniority that they are eligible to apply have had to fight so hard against the flow that they have no chinks in their armour when it comes to making applications. If this were true it would be expected to be the case that women assessed by physics, maths and engineering panels might be expected to be more successful than chemists, where the pool (at undergraduate level) is more even. The numbers are sufficiently small, and fluctuate sufficiently greatly, it is hard to test this hypothesis, but it is the case that PE5 (which covers much of chemistry) does seem to perform less well on this front than other PE panels over the years.

- Maybe there are differences in the style of writing between different domains and disciplines, so that there is a greater tendency to flowery prose/hyperbole/self-promotion in the LS domains and that the style that finds favour is more likely to be written by men than women. In this argument it is not the actual quality of the science that differs, but the style of presentation. The ERC has already changed the details that need to be given in the CV (e.g. by reducing the number of papers that can be cited as recent publications) to ameliorate any gender differences in the style of presentation of this part of the submission. A project is currently underway to try to examine differences in career paths (rather than actual presented CVs) between successful and unsuccessful applicants, both men and women, to see what can be learned about these aspects of the applications.

- Perhaps women are receiving less mentoring and institutional support to enable them to submit the best applications they can, based on the actual science they want to carry out. It is clear that the amount of coaching and other advice that applicants get can vary hugely by institution and department. This is a concern usually expressed when looking at the low levels of successful applicants from the EU12 group of countries.

- Maybe unconscious bias is present in the way panel decisions are reached by both male and female members of the panels. The extent of this may be affected both by group dynamics within any actual panel and the actions of the chair. This is perhaps the easiest problem to focus on. In principle simple interventions, including a quick briefing on unconscious bias at the start of every panel meeting might be thought to resolve this issue. This is an idea that is being considered further by the working group.

One of the reasons I felt particularly pleased when I was invited to join the Scientific Council was that it would expose me to disciplines very different from my own, including those in the Social Sciences and Humanities, and because it covers all of Europe and so would open my eyes to how things are done across the very different countries. As we discussed gender issues in full session, it became apparent that my experience to date has very much focussed on the English-speaking countries. On this blog I have written often about UK experiences, and a little about what I know within the US. Fellow Scientific Council member Matthias Kleiner pointed out to me that in Germany, during his tenure as President of the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), he introduced quite stringent expectations about German institutions funded by his agency. This, in 2008, was some years ahead of Dame Sally Davies’s statement about UK Clinical Schools, or the more recent statement, made earlier this year by RCUK. On the back of his actions, German institutions are already being assessed (as, I think, of this year) as one of 4 grades, thereby naming and shaming those who are doing little. There will be funding consequences.

Maybe other countries across Europe have funding agencies that have similar expectations around gender with real funding implications; if readers know of others do let me know. Naively, largely based on comments from German academic women of some years ago, I had thought the German academic culture was unfavourable for the progression of women. Clearly, there is a significant transformation underway. Let us hope that actions like these will help to improve the success rates for women in future rounds of ERC awards. It is hard to believe that the current levels, particularly in the LS domain, truly reflect the quality of the applications. In future years maybe comparable diagrams to those above will look very different.

Back in the days when I was an active scientist, there was some received wisdom that

i. The Southern European countries had higher numbers of women scientists at all levels than us in the North, and

ii. this was because being a university researcher/lecturer/professor had correspondingly less social prestige in those countries.

In your experience, have you seen evidence for any such geographical variation?

One possibility not considered above is potential bias in the reviewing process. I can’t tell you how many unbelievably talented and successful women I know have not even made it to interview and are then left with reviews that include comments like: ‘has great papers, but many are with her former PhD supervisor’, or ‘great project, but too risky/ambitious’. No doubt such comments undermine the panel’s confidence that the applicant can deliver the project.

Of course, I don’t know if men receive similar comments, but it would be interesting to know. One solution would be to withhold names and/or gender from reviewers and get an unbiased opinion of the proposal before asking the panel to judge the applicants track record.

The current situation is extremely discouraging for female academics!

In the case of ERC grants I believe the panels do the reviewing, so any advice to them on unconscious bias should ‘solve’ the problem you identify. I too have seen shocking referees’ reports which are gendered -see, for instance here.

I agree with Courtenay. I have sat on all too many interview panels where questions are raised over candidates’ ownership of joint work, their ability to deliver ‘on their own’, etc. My impression is that such comments are more common in relation to women applicants, though this is of course only an impression. But clearly, this must be a key issue in reviewers’ assessment of track record (remember the famous Nature study, 1997?). I also don’t think there is any reason to think that panels would be immune to such bias, particularly given evidence that senior women in STEM are just as susceptible to it (PNAS, 2012). Will alerting panel members and reviewers to unconscious bias help? i guess that the proof is in the pudding.

This year prior to our professorial salary round, all people involved had to participate in a half day training on unconscious bias, delivered by an external organisation that does a lot of work on equality. Will it have any measurable effect? I guess we will get some idea when the next equal pay audit is conducted. But my instinct is that a single half day training won’t have a discernible impact on the years of socialisation and stereotypes that got us here, and if universities, funding agencies, etc are really serious about equality, then it is going to take more than that. But clearly, this sort of initiative is better than nothing. It also seems that this area is ripe for some good experimental work on the effects of these kinds of interventions.

Like Courtenay, I also wonder how far gender blind reviewing of applications would go to addressing this issue.

On conference speakers, see this, about the ESEB meetings (European Society for Evolutionary Biology). The main (surprising) result is the higher proportion of women who declined invitations to speak. This is an n of 1, so it would be interesting to see similar analyses for other meetings.

Bob – yes I’ve been sent that paper and maybe will write up some thoughts in a day or two.

Courtenay and Kate The reason I mentioned refereeing was by panel, is that this means an out-of-line report of the kind you mention can be challenged in session (for instance by the chair) and if unconscious bias training does become the norm people ought to be sensitive to spotting such things. When the person writing a reference is not in the room, it is very hard to take comments at anything other than face value, and they can certainly be subtly gendered. As you say, it will take a long time for the effects of socialisation to be removed, but removing bias in references (personal or for a grant) ought to be slightly easier if people are aware of what they might be doing, all unintentionally. Interestingly, this aspect of women being more likely to be described as less independent, even at late career stages, is something that has come up in email exchanges I’ve been involved with over the weekend – in a completely different context. Clearly something that needs highlighting. All I can hope is the more these subtle differences are brought to everyone’s attention, the less prevalent they may become.

As for blind refereeing, I simply worry about the practicalities. Unlike an exam, when everyone answers more or less the same question, when you write a proposal you will be citing your own earlier work, preliminary data etc. It makes it hard to disguise who you are!

Are there any studies which show that proposals funded as a result of a peer review process are more likely to “deliver” than proposals funded as a result of being randomly awarded? I do sometimes feel that although we rightly insist on high standards of evidence for research, we do not insist on the same standards for grant funding. It would seem self-evident that well-informed scientists would make the best decisions of which research to fund, but it may well be that their pre-existing knowledge and unconcious bias could prevent them from making the best decisions. In any case, if our best scientists did not need to spend so much of their time on review committees, that in itself may result in a higher research output.