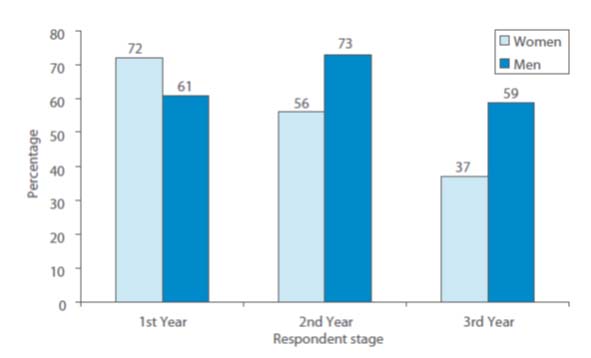

If you answered yes to the question in the title, a recent report suggests you may be a chemist, and more specifically a female chemist. A study carried out by the UKRC for the RSC about the PhD experience for chemists reveals some fairly unattractive facts that should give heads of chemistry departments serious pause for thought. In particular it can be seen from the figure reproduced here just how precipitous is the fall off in women who intend to continue in research during the 3 years of their PhD, with the figure approximately halving. In contrast, the number of men who agreed they wanted to continue in research, whilst it started off at a lower initial figure, was almost unchanged between years 1 and 3 and actually peaked in the second year. Here is food for thought for people who care about the loss of talent from the pool, and who look at the leaky pipeline in dismay. What makes the chemistry PhD experience such a particular turn-off for women?

- Proportion of respondents intending to pursue research on completing doctoral study by year and gender

This report builds on earlier work, dating back to 1999 (a report entitled Factors affecting the career choices of graduate chemists), and a later report (which I cannot find on the web) in 2008 explicitly looking at career choices by gender. The leaky pipeline seems worse in chemistry than other subjects, something that was reinforced by last year’s study about postdoctoral experiences in physics and chemistry which I wrote about here where, once again, female chemists were much less happy and much less sure they wanted to continue in research/academia than their male counterparts. A 2008 report comparing chemistry and biochemistry PHd student experiences likewise demonstrated that chemistry students (female) were less satisfied overall. The discipline of chemistry seems out of line with other subjects when it comes to how women experience it.

The current report is based on interviews with men and women during their (chemistry) PhD’s, both as individuals and in small groups, and the results are pretty dispiriting. Even though the numbers involved in these interviews are quite small, the results amply back up prevous findings involving much larger numbers. I will only highlight a few points here, but I would urge the concerned reader to read the report in full – it is fairly short, at least if you don’t read the annex which has many of the actual quotes included. Broadly speaking it is clear that the women were much more likely to be got down by poor supervision, by feelings of isolation and by the slow progress of their research than their male colleagues. But they also seem to have been more likely to feel uncomfortable with the culture ‘especially where the culture was particularly macho’ and not infrequently to feel poorly integrated or even excluded and bullied within their research group.

Now, the more macho supervisors out there may immediately feel that this is due to weakness in the women, that they lack something that makes them suitable for a research career and the sooner they are weeded out the better. That would be to approach the problem via the so-called deficit model which implies that the failing is in women who can’t manage to fit in, integrate and be like the boys. However, perhaps the macho culture weeds out a certain kind of person – who may be male as well as female – and that as a result a reinforcing pattern of unpleasant behaviour, rather than an optimised way of doing research, ensues. It seems to me that a culture within research is deeply flawed which leads to the following statement:

During doctoral study, a larger proportion of female than male participants had formed the impression that the doctoral research process is an ordeal filled with frustration, pressure and stress, which a career in research would only prolong; rather than short-term pain for long-term gain.

Of course this macho culture is not the only thing that women find discouraging. It is inevitable that, for many of them as they look ahead to the uncertainties of short–term contracts if they opt to stay in academic research, they worry about the implications for family life. As a result they

Come to believe they would need to make sacrifices (about femininity and motherhood ) in order to succeed in academia;

and

Been advised in negative terms of the challenge they would face (by virtue of their gender).

On the former front there should be far more effort put into highlighting those women chemists who have succeeded in combining motherhood (and even femininity) with successful careers. This is something we try to do in Cambridge in various ways, but notably this past week we had a wonderful talk by Carol Robinson, who has undoubtedly succeeded on all these fronts. Here is a woman, an FRS, winner of many prizes, who not only had 3 children (now adult) but took 8 years out of research when they were small. She came to give Cambridge’s Annual WiSETI lecture last week, to a packed audience. This is the sort of life-history that should give hope to all those wavering female chemists who simply believe ‘it can’t be done’. It can.

There are many recommendations made in the report. I single out just a few here:

Training supervisors better, particularly about equality issues but more generally about providing support and encouragement to those starting out on their research careers;

Setting up networks to prevent feelings of isolation and discouragement, and better mentoring perhaps via a buddy system;

Acknowledging the role postdocs may play in PhD student supervision, but also ensuring they too receive training and also recognition of this important role;

Assessing departments on the basis of the quality of their students’ training and the quality of their experience, for instance through Athena Swan awards.

Which brings me full circle. This report was originally coordinated by Sean McWhinnie and Sarah Dickinson, when they were employed at the RSC. They both left several years ago. Sarah at that point joined us in Cambridge as the WiSETI project officer, a role she fulfilled admirably and with her last main task being the WiSETI lecture I mentioned above. She has now moved on again and will be heading up the Athena Swan team at ECU and so, in principle, could move to include the PhD experience in assessment criteria. However, it is very clear that Athena Swan is going to have its work cut out for the foreseeable future, with a flood of new departmental applications anticipated in the months ahead. This is a direct result of Dame Sally Davies’ requirement of Clinical Schools that they have Athena Swan Silver awards in order to be likely to receive further funding (as I described here), accompanied by other funders making noises that they may follow suit in some shape or form. Consequently, I suspect that Athena Swan may not make such changes fast.

However, let us hope that chemistry department heads read this report and reflect about what they can locally do.This and previous reports suggest there is something peculiar about chemistry as a discipline that makes things seem so particularly tough for women. Indeed, as some of the comments in the annex to the report make clear, synthetic chemistry seems even worse than other sub-disciplines. If asked to speculate, I would suggest this may be because groups in synthetic chemistry tend to be very large, with PhD students being seen simply as a useful pair of hands. It is all too easy for the individual’s needs to get lost in such a synthesis factory. Nevertheless, for the good of future research I hope that something will be done to improve the working atmosphere for everyone, and not just perpetuate a certain type of machismo.

Given the number of research jobs in chemistry, both in industry and academia, another reading of these statistics might be that female students are much more realisitic and practical regarding their future, than their male colleagues. There are no guaranteed jobs in science to match the large number of gradaute students in chemistry. The reasons for the large numbers of Chemistry PhDs, are complex, the ‘tradition’ in synthetic chemistry of having large groups in order to be productive is one of them. It is of interest that the only subject that requested phd numbers to be included as an addional returnable fact in REF is chemistry.

So the comments by female students are of concern, but when people decide to leave a profession, it is usual to be negative about it. It is of equal concern that so many male students think they will have a job in research afterwards. I would suggest that they are equally misguided.

Of course we want the best people to stay in science, regardless of gender, but would contend that there are more disapointed postdoctoral males than females, and further that females probably realise earlier that a phd in chemistry leads to many career options.

I think I always assumed (as always, looking in from the outside) that a PhD was supposed to be a bit of a trial!

Most of the chemists and biochemists I know are women and they seem to enjoy their work. Obviously that doesn’t prove anything about the larger numbers, but it gives me hope. Some women have succeeded in this field. Others can too.

Perdita

I agree that that may be a reasonable alternative explanation. When I discussed, in my previous post, the report on chemistry and physics postdocs, I said something very similar:

The former may be explained by women jumping ship because they aren’t happy, but it may also be they are more realistic about career options.

But althought they may be more realistic on average, that doesn’t mean some women aren’t leaving for bad reasons, and some of these women may be ones who could indeed have succeeded if they had been in a more conducive atmosphere. Statistics can never reveal things like that.

Owen

I think what you say is equivalent to saying everyone should just grin and bear a system that instead maybe we ought to be confronting. No one ever said research was easy, or that things will always go right, but good supervision is separate from easy research, and encouragement when things go wrong, slowly or even incompetently might be better all round. I know when I kept breaking things during my own PhD I was lucky enough to have a supervisor who said to me he would only worry when I broke this particular piece of apparatus 10 times out of 10 (at the time I had only reached 3/3 – and I think after that I didn’t break it again).

It would be interesting to know what the breakdown of the leaky pipeline is by topic within chemistry.

There is particularly nasty attitude problem amongst the organic synthetic chemists (100% in my sample of 3 chemistry departments) that says that if you aren’t chained to the fume hood 8am to 8pm then you aren’t serious about your work.

I know someone (with 3 kids himself) who recently removed almost all of the computing equipment from his groups office on the basis that any writing up, graph plotting etc. should be done at the weekends/ in the evening as 8 till 8 time was just for lab work.

Now it is my strongly held opinion that synthetic chemists would actually make progress faster if they stopped and actually thought about what they were doing once in a while.

But this attitude is self-perpetuating, as only the people who like to work all day (sometimes without bothering to switch their brains on) will survive the regime to become postdocs or PIs. The reason that women leave this particular area is because they are too sensible not to.

I have found the difference between physics departments and chemistry departments to be enormous on this front. I spend most of my time in physics and hear/ know nothing about my colleagues work habits or work life balance. Everyone just does what they want/need to without passing judgement on anyone else.

I cannot spend 30 mins in the chemistry department before someone tells me they were in all weekend working on x, y, or z and incidentally that they think all their students need a kick up the backside as they have been seen (shock-horror) in the tea room!

BB

I don’t think I have ever seen a breakdown by chemistry sub-discipline of what the leaky pipeline looks like. I think your comments about the difference between chemistry and physics is telling, but you don’t actually say synthetic chemists are even more likely to spend a minimum of 12 hours at the bench than, say, a physical chemist, although you rather imply that. I think there may be brief periods when insane hours seem the right thing to do, but personally I have never felt it necessary (nor do I know many other PIs who have) to tell my group what hours I expect them to be around. What I do expect is progress and professionalism (eg being well prepared for conference talks and visitors). It seems that the RSC might be wise to look further behind the statistics, but that in itself won’t change the culture.

My other half did a PhD in the chemistry department – he used to have to go in at night and weekends to top up the dewer – cheaper than automating…. he bought a mini telly…. definitely a weird chained to the instrument mentality…. I have to say the cav. was far more sane, always remember MP a prof in TCM working at home to look after his youngest perfectly openly, same guy used to funnel his IP profits into paying for a nice coffee machine for his lab, free IoP membership and we adored him… in chem. they bragged a lot about their performance sports cars… in lectures!!!! Chem@cam is hilariously boasty….

Athene,

Yes I was definitely meaning to imply that synthetic chemists do this more than other chemists! The actual groups I have been in have not been of this nature at all, but you only have to share the corridors with the others to know all about their commitment to their work…

I don’t think that it should be very hard to break this cycle….all it would take is for department heads to impose maximum working hours on students and postdocs – and to actually follow up that there recommendations are being adhered too. You could do worse than shutting the department for all non-essential experiments outside of office hours….I remember the Cavendish doing this during the fire service strikes…I doubt it impacted productivity one jot (although I did know a nocturnal PhD student that it seriously inconvenienced).

I will also never forget visiting industry contacts in the Netherlands and witnessing the mass exodus at 1pm on a Friday. Not just shop floor people but management too. ‘We have done our hours so now we all go home’ was the prevailing attitude.

I wonder if they have better female retention? I am sure we could learn from them!

I agree that false expectations among male participants would be as big an issue as women who could of have succeeded leaving (or vice versa) and be equally as deserving of action. Could some indicators of participants suitability to do research or research in academia e.g. numbers of papers published from the PhD, numbers of patents, numbers of oral/poster presentations given, short questionnaires to supervisor one and two and external examiner for opinion (anonymous) be useful in a study like this? If someone is not suitable for research then should the money have been spent on this PhD when there are limited funds for science? I know this person will still have learned a lot which they can take elsewhere but the money could be spent on someone who could learn a lot AND produce useful research outcomes (benefitting society) and communicate them during the PhD. Wouldn’t it be better to fund fewer PhDs in chemistry and to have stricter requirements to start a PhD e.g. compulsory minimum of 1 years postgraduate work experience in a relevant area, a compulsory MSc, ability to map work for the first 6 months of the PhD. The money saved could be spent funding those who do have the required qualities to do research (and want to stay in academia) to carry it out as Fellows or more/longer post docs instead of them leaving. Those of us lacking all of the required qualities to do academic research would possibly be forced to this realisation sooner and have more time to find some other way of making a useful contribution to society!