A PhD should comprise both education and training. It should not be slave labour or done in blindness about where it might be leading. But I fear these statements don’t always apply. In the research grouping in which I sit at the Cavendish, which now has quite a large number of attached staff and research fellows, we try to provide a programme both of locally relevant pedagogy and more general talks about research skills: topics students might find helpful, regardless of what they end up doing next. So, when it came to my turn to give the week’s lectures to the 1st years I chose to include material concerned with preparing for life beyond the PhD. In other words, I used the well-known Figure 1.6 from the Royal Society’s 2010 Report, The Scientific Century, to provoke thought.

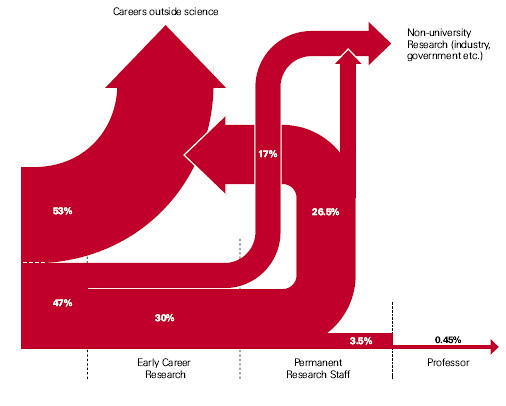

Just in case you don’t know which figure I mean, I reproduce it here.

It is the final number on the right hand side that tends to focus the mind of even the most confident student. Of the pipeline that starts off in science a mere 0.45% ends up making the grade as professor. Clearly a large number of STEM graduates never intend to stick around in science per se, though they may well use many of the skills they acquire during their degree in subsequent employment in management, banking, primary school teaching or retail – to name a few common graduate destinations. As a result there is a large drop in numbers very early on. But what about those who stay on and do a PhD. What does this cohort think about their futures?

For some I fear the answer may be they don’t think about their futures. Period. Not at all. Nor do their supervisors encourage them to do so. Once upon a time it may have been adequate to start contemplating one’s future as the ink metaphorically dried on the thesis-writing, but those were the days when a large millstone of debt was not likely to be hanging around the neck of the student and maybe they felt they had time to ‘find themselves’. Certainly I have had at least two students who were quite sure what they wanted to do upon completion was to head off to Australia and tread grapes by way of sunny relaxation whilst still earning enough to fund a subsequent trip around the Pacific. Indeed one of these students thereafter settled in Australia. But such easy-going times are probably past.

The time to start thinking about what next is very early on in the PhD, in order to give oneself time to explore one’s skills, strengths and weaknesses. Time to ask awkward questions of anyone and everyone (but most particularly the careers’ folk who are likely to know far more about life beyond the university walls than most supervisors) and time to try out a few things on the side as your research slowly gets going. Maybe you can find an opportunity to teach, to write for some local science magazine or get involved with Skeptics-in-the-Pub or more conventional outreach activities. Time to explore if there are options to get a placement in industry or in policy (various funders provide funding for 3 month placements with POST, the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology). Time, in short, to think whether or not academia is for you and if not whether you might get more satisfaction elsewhere.

The trouble is that too often the message is conveyed and received that anything outside academia is Failure, writ large. Wrong. Staying in academia when it isn’t right for you, staying simply because you can’t think what else to do, or staying because you feel frightened to try out something new is the failure. As a supervisor it is never pleasant to say to a student you’d be better off elsewhere but that is quite often bound to be the case. Not everyone is cut out for research and it would be very boring if they were; it would also leave great holes elsewhere in our economy! But, as one blogger implied recently maybe the system is failing when it doesn’t kick people out fast, not when it does.

Students need to have realistic expectations about what opportunities there may be. Supervisors have a duty to try to instil this and facilitate exploration of opportunities outside the lab. I fear neither party always does a good job of adhering to these statements and that is when things go wrong. Doing a PhD may teach you all kinds of useful things but it should never be seen as an automatic passport to a permanent position. By default, by both parties burying their head in the sand, too often this unspoken assumption can go unchallenged and that’s when things can end in tears.

Maybe one of these days someone will sit down and work out how many students we actually should be training and for what purposes. There are many and diverse jobs that benefit from the skills of a PhD-trained individual, so consequently that would be a hideously complicated sum to attempt to do. There is no sign that the Research Councils (or other funders) think deeply about this as they assign money to this or that new fashionable field, Doctoral Training Centre or whatever, let alone looking across the STEM landscape and checking that the terrain is the right shape and doesn’t have pathological bulges or deep pits of absence. Without such horizon scanning, students and supervisors will continue to muddle along. But at the very least they should muddle along with some awareness that life outside academia should be scrutinised very carefully from an early point and that skills beyond the merely technical could usefully be acquired.

Some years ago the Athena Forum, which I was then chairing, produced a template for a bookmark with a set of ten questions designed to help postdocs think about their futures but it seems to me these questions are equally appropriate for students contemplating the great unknown. I reproduce them here:

- Are you on the right career path?

- Are you ready for the next step?

- How’s your life/work balance?

- Why do you enjoy what you do?

- What are your strengths?

- What motivates you?

- What is your next step?

- What skills and experience do you need?

- How can you gain these?

- Where can you go for objective guidance?

For students not to start seeking answers to these and related questions at an early stage is a recipe for subsequent disillusionment and job worries. These questions should be answered whether one is dead set on staying in academia or quickly realises that research is not one’s forte. Either way recognizing one’s strengths and weaknesses and the skills that could usefully be acquired on the side can only be beneficial.

As always, timely. I’ll be passing it on. Thank you. It is timely because anyone further along in the pipeline has a moral duty to think about these questions regularly on behalf of the people coming up behind, and this echoes a conversation I was having but yesterday, as we have some new talent in the lab. It also came up after a rather depressing meeting among supervisors on Thursday.

You wrote: “Supervisors have a duty to try to instil this and facilitate exploration of opportunities outside the lab.” We had been lamenting the apparent lack of interest and follow-up on behalf of those people for whom some of us had been making active efforts in this direction, despite such efforts being well outside of our personal comfort zones. Our desire is not to repress all blitheness and optimism, but to encourage even our best trainees to consider alternatives while still pursuing their goals.

We also discussed how disparate work ethics can destroy the solidarity in a laboratory, or even a department. Hiring decisions are nearly entirely out of permanent researchers’ hands in France, aside from student recruitment (and even then, it is restricted to a right of refusal). Thus, a few people regularly slip through whose apparent motivation and goal is to minimize the work they provide in exchange for a mediocre salary, but often generous benefits and maximum vacation plus sick days. Hardly a recipe for planning out a career path, and it redistributes an additional burden of work on the more conscientious. Of course, this must afflict all professions. But it’s also our duty to remind aspiring future scientists that ours are jobs that are most rewarding when it is a pleasure, rather than a duty, to come to work.

I feel that I ought to comment on this.

Academia isn’t for everyone, and there’s an enormous amount that a PhD gives you beyond knowledge in a specific area. I’ve had the good fortune to work for a couple of companies who realise what that means and actively try to recruit recent PhDs and post-docs. Don’t expect lots of companies to understand this (there are of course a relatively small number of PhDs), but they do exist.

So come and join us: we want you!

Oh, and I’m not sure I agree with the “kicking people out earlier” idea.

I agree with all the sentiments in the post, but want to point out that the figure (much reproduced) from the Royal Society report is inaccurate. I wrote the report (What Do PhDs Do?) from which the first split of the arrow is taken. Rather than 53% leaving science, it should report that 53% leave the academic sector. Many of this 53% stay in science, at least initially, as they go onto roles with industrial and health sector employers ( the % varied with discipline). When you look at the figure again, this probably makes sense as it seems to suggest that no PhDs go into non-academic scientific roles.

In the years since I wrote WDPD data collection has improved and there is a lot of information on the Vitae website about initial destinations of PhDs and reports into postdoctoral career paths:

http://www.vitae.ac.uk/policy-practice/513201/What-do-researchers-do.html

With this slight edit, I also use this diagram in my workshops with PhDs and postdocs to make the same points as you – that if you intend to follow the academic path, you need to be focusing on research outputs, visibility and reputation. I also make the point that if you intend to leave, that you are not one of the “let downs” but in fact in the majority and that a PhD is a path into a huge range of career options – start exploring these early and you’ll have time to develop the skills needed for your prefered career.

This doesn’t mean that academics have to become experts in non-academic career paths. Encourage students to use the University Careers Services they have free access to – the more researchers engage, the more careers advisers will understand and be able to help them. However, I agree that supervisors need to accept that their researchers will need a broader range of skills than they will develop “at the bench”.

Thanks, Sara, for the clarification. I admit I was a bit baffled when I first studied the figure but in this case I wasn’t interested in the LHS of the figure.

Owen – hi! You were, I recall, one of the Australian grape-treaders (was that the literal case?). I should make it clear I wasn’t suggesting chucking out students half-way through their PhDs, just not encouraging people to hang around doing postdocs when they really weren’t suited to it. A postdoc position can seem like the next logical thing when really it is only the easy choice which requires little thought. For many it can be quite demotivating and/or disillusioning. Thanks for stressing the lure of industry.

Athene – hi! No it was just the grape picking I’m afraid. No treading.

I realise you didn’t mean kicking people out part-way through a PhD.

There is, of course, a difference between encouraging someone to leave because you think they can’t do it, compared with pointing out to them that there are alternatives (even fruit-based).

Great and wise post Athene and one I will be sharing with my PhD student friends. I certainly recognised the ‘everything else is a failure’ feeling, and also the experience that my supervisor was not the place to go for objective careers advice!

One note of qualification though. While I agree it is possible in many cases for both students and their mentors alike to tell they’re not suited for the academic career path by the end of their PhD, there is also a significant cohort of excellent students who both want a shot at an academic career and whose mentors believe they have a realistic chance at achieving their goal. This cohort is however significantly larger than the one that actually WILL end up in tenured positions and their mentors predictions of their probability of success may not always be spot on. So I feel as if they are the ones that need perhaps need your advice the most.

We rightly want to encourage this group to commit fully to pursuing their ambition (and produce some super science along the way), but we are failing them if we do not also push the message that they really really need to plan and train for the quite significant possibility that they will not be one of the chosen few.

Great post, and I too will be passing it on! One niggle though – I may be alone in this, but I think language like “a mere 0.45% ends up making the grade as professor” may contribute to the feeling that leaving academia means you have failed.

If we view academia more as another normal job (which I really believe it is), and use language less associated with school, then maybe these views might fade – and the taboo of wanting to leave academia might fade.

Out the world beyond academia, not everybody wants to be senior management/CEO – and it’s no different in within academia – the pressure we put on eachother is nuts.

Amber – Interesting how you read my sentence. It was meant to indicate not a sense of failure, but a recognition of the fact that it’s always going to be a tough challenge if academia is all you have in mind. I think one thing students don’t appreciate is that being good in the lab (or at the computer or with theory as appropriate) is far from all it takes. Being brilliant at the bench is not enough without the ability to dream up your own experiments, write – grant applications or papers – teach and much more. Perhaps most importantly of all is the ability to multitask and still keep going while all the balls are guggled. These additional skills only become apparent as one progresses; at the outset doing excellent research is the only thing that may appear to count.

Hi Athene,

Another wonderful blogpost. It has inspired me to write about my own pipeline experience and the benefits of thinking sideways as postgrads move on in their academic careers. So many issues here to pick up on – but space is limited and so is full reflection time. Link to my post.

Best wishes,

Hilary Geoghegan,

Lecturer in Human Geography, University of Reading

I think you’re flogging a dead horse at this point and PhDs know the score better than you think, as evidenced by the figure form 4 years ago showing the majority of PhDs don’t even spring for a post-doc. Talking to students who do fancy that route, some see it as two years in a different country or to gain a bit more training or as a stop-gap—I’ve not met one who sees themselves as a shoo-in professor, give them some credit.

Also keep in mind that conversations between students and staff may not bely their true ambitions. Many a grad student will butter up their superiors with academic aspirations while discussing the best way into “management consulting” or some such with their friends.

A final point (I know academia is well-distanced from the real world), but what do you think an ambitious young intern at Goldman Sachs enters thinking? Oh, only <1% make partner, better think about working elsewhere? Of course not, everyone has aspirations against the odds and has to come to terms with that in their own time.

The NSF pegs the number of US-based STEM PhDs who get permanent academic positions within 3-5 years of graduating at 22%: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind12/c3/tt03-20.htm

22% is a low number, for sure, but it’s not 0.45%. Is the academic job market in the UK really that much worse than in the US? Or is there something wrong with the Royal Society’s figure …

Thanks for that Rob, that’s very interesting but I’m not sure I read that table you link to as you seem to be doing. Without having seen the text around it it’s hard to be sure but it could imply that those numbers refer to the percentage of those who are still in academia rather than the total percentage of all doctorates. Because, to be honest, 22% (where do you get that headline figure from by the way, as it seems to vary massively between fields) seems quite high given the needs of industry etc for skilled workers. Nevertheless, the 0.45% referred to in the Royal Society report is very different because ‘professor’ in the UK would be the equivalent of a Full Professor in your parlance, not a tenure track position. The UK may be very different in other ways too, because the PhD tends to be shorter here, which may encourage more people to start off. Many of those probably never do intend to stay in academia. It is those that do and then find the jobs aren’t there that this post is really addressed to.

If other people can comment on the different apparent structures in the USA it would be very interesting to hear.

Athene:

From the footnote to the table: “Proportions calculated on basis of all doctorates working in all sectors of economy”

The surrounding text is here: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind12/pdf/c03.pdf

Hi Athene, the statistic is legit. Two things: there’s wide variation between fields. And there are hundreds of small private universities in the US that employ PhDs in tenure or tenure-track positions. Even so, I think 0.45% seems way too low for the UK. I’m a postdoc in the UK at the moment in a STEM field. I would peg the percentage of UK-based postdocs who eventually get a permanent academic post somewhere in the world at about 20%. But I’m also at a great school, so there could be some selection bias going on.

We have a friend in the UK who is a professor, but she is American with an American PhD. Are British uni just not hiring British PhDs? Or is she an anomaly?

Rob, I think there may be a difference in terminology here. In the UK, people aren’t called ‘professor’ until they have reached the pinnacle of their career. It’s not an entry-level or even mid-level position and indeed only a tiny percentage of graduates ever reach it. In the US, as you of course know, people are called professor when they have an academic job of any kind.

Perhaps an overly simplistic calculation, but doesn’t this figure imply that each professor would have to graduate, on average, 222 PhDs during their career? That is, assuming that one replaces them when they retire with the other 221, or 99.55%, going off to other careers. Even if one assumes that permanent research staff are able to graduate PhDs, they’d still have to average nearly 29 each to maintain a steady state based on that graph. Those figures seem unlikely (I know some individuals might achieve that sort of number, but I can’t see it being a universal average). Either the number of permanent positions is falling rapidly, or someone’s calculations (mine perhaps?) are very misleading.

The graph represents a variety of reports that don’t really fit together in the elegant way the image suggests. I wrote one of them and the data is mis-represented (see my other comment) so you might find a more accurate picture from the source material (linked to from the RS report). A look at jobs.ac.uk gives anotherview of the current academic job market in the UK and it would be interesting to see an analysis from them about recruitment patterns (I’ve asked!).

Hi, I’m a current PhD student in the UK. At the moment I am leaning towards trying to go into academia, but I’m not sure yet. I think you’ve put me off a bit actually. This comment has turned into an essay, so my apologies!

Firstly I think you underestimate the amount that we consider our future. The majority of my peers are aware that they can go into academia or industry or teaching or something else entirely. It’s just that they have no idea which they want to do, which they would be best at, which would be the best for them, and they don’t know and are not confident in whether they actually have the ability and skills to pursue some of them. That doesn’t mean they aren’t trying to work it out. “I don’t know” is not necessarily equivalent to “I haven’t thought about it” or “I don’t want to think about it”.

I also think you underestimate quite how terrifying this stage of life is. I have no idea how my future will turn out, and if I make the wrong decision then that will have a very big impact. The question is so big and the answer is so important that it really is very scary, and I somehow feel far too young and ignorant to be responsible for making the decision, let alone implementing it.

Secondly I agree very much with Amber above that it comes across in your language that academia is success. You talk of kicking people out of academia, of a mere 0.45% making the grade, how not everyone is cut out for it. To me this does imply that you think academia is the ultimate peak, the goal that unfortunately not everyone is capable of reaching. If my supervisor told me that I need to have realistic expectations about what other opportunities there may be, this would set me up for a massive spike of Imposter Syndrome. “I need to be realisitic? They don’t think I can do academia. They don’t think my work is any good. They don’t think I should be doing a PhD. Why am I doing a PhD? Can I do it? What if I can’t? I’m going to fail everything. Why did I try to do this? I’m not smart enough for this”. Your previous posts would suggest it’s relatively common for people to be underconfident, and believe me that is the coherent sensible version of what my train of thought would be!

Finally, there is a vast difference between somebody trying to go into a career outside of academia and doing so (success!) and somebody trying to go into academia, not achieving this, and going into something else instead. The latter may make a complete success of their life in numerous ways, but if you try to go into academia and don’t manage it, then you have failed to become an academic. I honestly don’t know how else you would describe it. I think the point you are making is that failure at academia is not failure at life overall, and actively deciding to do something else isn’t failure of any sort… but failure at academia is still failure at academia, and to not acknowledge this seems, well, not great, especially coming from an academic.

I still don’t know what I will decide. People tell me I have potential, but I don’t know whether I believe them. Academia has few jobs, no job security, no stability, too much misogyny, and frankly might cause me a nervous breakdown. It also has teaching, and those amazing moments where research is the best thing in the world, and I genuinely love the intellectual bashing my head against some obscure problem just because I don’t know what the solution is. Industry has more money, more stability, but I would never use the knowledge (skills yes, knowledge not a chance) from my field again and I’m worried I would have to sell my soul to a company doing immoral things. Going by friends’ experiences it might be very boring and I don’t know how to test that before jumping in completely. It seems very all or nothing, and I’m running out of time to pick. Which should I choose?

At least I am thinking about it 🙂

Sara – thanks for the additional clarification.

I reproduce here the caption for the original figure in the original Royal Society report and the references so that people can go back and check the data (though it’s now quite outdated).

This diagram illustrates the transition points in typical academic scientific careers following a PhD and shows the flow of scientifically-trained people into other sectors. It is a simplified snapshot based on recent data from HEFCE (33), the Research Base Funders Forum (34) and from the Higher Education Statistics Agency’s (HESA) annual Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education’ (DLHE) survey. It also draws on Vitae’s analysis of the DLHE survey (35). It does not show career breaks or moves back into academic science from other sectors.

(33) HEFCE (2005). Staff employed at HEFCE funded HEIs. Trends, profiles and projections. Higher Education Funding Council for England:Swindon, UK.

(34) Research Base Funders Forum (2008). First Annual Report on Research Staff Covering the Period 2003/04 to 2006/07. Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills: London, UK.

(35) Vitae (2009). What Do Researchers Do? First Destinations of Doctoral Graduates by Subject. Vitae:Cambridge, UK.

I think people shouldn’t get too hung up on whether the figure is 0.49% or 4.9% or whatever because it’s clearly not that precise. What matters is it’s small. I first read the figure as the percentage of those who embarked on a STEM degree rather than on a STEM PhD – the percentage seems more plausible then. But it is bound to be flawed. There has been an expansion in student numbers (PhDs anyhow) recently, funded by multiple routes and of many nationalities. The number of professors reflects those who progressed from PhDs 20+ years ago so it’s bound to be a very imperfect match.

Me – I can only say again my intention was absolutely not to convey leaving academia is failure, which I strongly don’t believe. I was merely commenting on the figure. It is excellent if you and your peers are thinking hard about the issues I raise. However it may well be that you are in a favourable enclave, as it were, led by a PI who themselves understands the issues. Possibly one who even facilitates the discussion. Many other places may feel very different from that. My experience of chatting to students is that what you describe is far from common. The comments about this post (and indeed phenomenal interest in it) suggests not everyone is as fortunate as you.

One of the things I find very disappointing is hearing stories of students who are in essence forbidden from spending time on anything away from the bench; or of groups where 2 students are set up in direct competition so that one is bound to fail. All students should be able to explore options and all of them should be encouraged to do so.

NicoleandMaggie – the number of UK students staying on to do PhDs has fallen as a proportion of the graduate population. And hiring of professors will comprise many nationalities. The UK nationals are neither favoured nor disfavoured I would say – as is correct in a meritocracy. I think one thing that is evident is that UK universities are seen as favourable places to work so people are attracted to work here from around the world.

The following was something I was writing earlier today that was going to be a blog post, but having just read Professor Donald’s eloquent comments it actually fits better here. Getting the tone right can be difficult and in this case the writing sounds a little like “oh poor me, denied my rightful place in academia”. This is not the case, I am happy with my job in industrial research and have never considered anyone owed me a job anywhere. The issues Professor Donald addresses are emotive ones, and this is not an objective view but rather how it felt for me to leave academia. To my surprise, for one used to providing logical reasoned explanations, I think this actually provides some insight into the problem as a whole.

I love my current job in industrial research, however I still feel guilty at having left academia. The main reason is that I see science not just as a job, but as a true vocation – what I have always wanted to do for the rest of my life. Universities are for many the pinnacle of this vocation, and the only place they see science being done. Some who have done a Ph.D. and postdoc have this badly, and apparently that includes me.

Getting a faculty position is deliberately difficult to weed out those who don’t make the grade in Professor Donald’s unintentionally apt phrase. Even with the positive feedback of being shortlisted and interviewed at multiple prestigious universities, if it doesn’t pan out the doubts begin. Continue to pursue the dream and you are putting off life (settling down, having a family, actually purchasing a house), but if you accept a ‘regular job’ you have given up your dreams of many decades. At this point the guilt begins to set in, you are about to give up your dream for a few pieces of silver you need to put a roof over your head and food on the table. Given that it took considerable hardship to train for what you believed in it seems a particularly harsh pill to swallow. What a fake you really are. This may seem a surprisingly narrow view of life, there are many other things you can do as a Ph.D. science graduate, but the point here is that this is what it feels like. There are many parallels with the acting profession I see here in Los Angeles.

The situation is not helped by some vocal faculty members (an indeed some postdocs) that reinforces this: they are good enough and the unsuccessful are merely failed scientists who need to go away. This view is surprisingly common, and in my experience more so in the smaller university departments – the larger ones have a belief that there are lesser institutions that will take the remainder who want faculty positions.

In searching for a job we look to others for positive feedback to determine whether we are on the right track. In this case there is ample fodder to support the view you should continue: we are constantly being told that the country needs more scientists by sources as diverse as the government and the universities we work in. A large number of us have also been told by people with permanent positions that there would be academic jobs in the future with some plausible explanation – in the 90s in the UK there was the argument that the large cohort of faculty members hired during the expansion of universities in the 1960s were getting close to retirement and there would be jobs for those who hung in there. The surprise was discovering that this argument was pervasive and widely believed by most postdocs of that generation I know. There are equivalents in other countries (e.g. I now live in the US and hear similar stories), and clearly modern day versions of these stories from well-meaning individuals.

The point is that you get yourself into a real mess because you don’t see any way of pursuing what you want and have trained to do. There was no obvious way to discover what else might be a really good fit. Having previous students and postdocs visit academic labs and talk about their jobs would have been incredibly useful.

“Maybe one of these days someone will sit down and work out how many students we actually should be training and for what purposes. There are many and diverse jobs that benefit from the skills of a PhD-trained individual, so consequently that would be a hideously complicated sum to attempt to do. There is no sign that the Research Councils (or other funders) think deeply about this as they assign money to this or that new fashionable field, Doctoral Training Centre or whatever, let alone looking across the STEM landscape and checking that the terrain is the right shape and doesn’t have pathological bulges or deep pits of absence. Without such horizon scanning, students and supervisors will continue to muddle along. But at the very least they should muddle along with some awareness that life outside academia should be scrutinised very carefully from an early point and that skills beyond the merely technical could usefully be acquired.”

I wonder if this is akin to the challenge researchers have in publishing negative results?

In the last few years the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) has commissioned three pieces of research to consider the questions you’ve raised. All three have essentially come back with the result ‘too difficult’. So the information wasn’t published on the NERC website but it has been discussed by colleagues and NERC advisory boards, and the ideas continue to be discussed when we consider what to fund – see the NERC success criteria for Postgraduate Training. The ‘too difficult’ answer also resulted in the instigation of the NERC-led Skills Review which undertook horizon scanning to look at the ‘what’ skills gaps there are rather than ‘how many people are needed to fill the gaps’.

As the manager of that review I acknowledge the many methodological issues it presents. But it did give NERC (and other funders) something to work with, and I know it has been welcomed by students considering a PhD – and it highlights the high-level skills needed by a wide-range of employers.

The review can be found here: http://www.nerc.ac.uk/funding/available/postgrad/skillsreview/review2012.asp

NERC Success Criteria for Postgraduate training can be found here:

http://www.nerc.ac.uk/funding/available/postgrad/documents/success-criteria.pdf

@kirstygrainger

The issue of who goes where in the education pipeline and the problems stemming from the small number of academic jobs compared to the supply seems to be much lower in engineering compared with the sciences.

Engineering, like computer science, has the considerable advantage that the majority of the real action is clearly happening in industry rather than universities. Think Google, or Scaled Composites or Apple: the boundaries are being pushed there – the ideas may have been spawned on campus but it is only in the big world outside that they get to be really exciting areas to work in and maybe change the world. Biology is saved by the medical connection, which is where much of the excitement in the current revolution is focused. The point is that with this mindset there is a natural outlet for talent that does not imply the best are only to be found at universities, and it is a much bigger pond out there.

Physics and to a smaller extent pure biology have a real problem here as the companies that use these people do not call those jobs ‘physicist’ or ‘biologist’, they are all something else which makes it hard for people to understand that those who trained in these disciplines are making a real difference in these positions. We need a way of relating the jobs in industry to the scientific content that is just not there at the moment. Physics in particular seems to define itself by what is left after everything else has been put in a different category. This preference for ivory tower obscurity in physics and inclusiveness in engineering is even found in the professional societies – compare Physics World’s “Once a Physicist” column about someone who has moved on from physics to the IEEE’s spread on “Coolest jobs 2014” about what is happening in engineering. It isn’t fair for me to pick on Physics World – it is by far the best publication on physics there is and has done remarkable work in creating an interest in the subject, but it picks up on the zeitgeist of the community it serves.

We are quite happy to consider chemical engineering, computer engineering and electrical engineering as thriving disciplines that feed into an industrial research and development engine. Maybe it is time to consider physical engineering and biological engineering as their counterparts in the other sciences that seem to define themselves only in terms of what they see in the mirror.

Great post, and certainly one that I wish I’d read at the start of my PhD!

I just wanted to point out that the academic track is not the only one that can be found within academia. There are a lot of roles that require a deep understanding of a domain and of research methods, but aren’t classified as research roles because the people involved don’t tend to write papers. I’m thinking about research technologists here – and especially research software engineers, many of whom are qualified to PhD level.

It’s not currently known whether there are enough research software engineers and other research technologists to skew the figure in your blog, but it appears that the numbers are rising with the ever increasing importance of skills in software, data, visualisation, etc. in research, so it may well need to be considered in the future.

The statistic stating “Of the pipeline that starts off in science a mere 0.45% ends up making the grade as professor”. Where is the data for this? Does this include individuals who started majoring in science during college who make it to a position as professor (after tenure)? If you can provide a reference for some of these statements that would be helpful. Thanks.

There is a link to the report from which this figure is taken in the main text. Each individual report used in producing the figure is individually mentioned in a comment from Athene above (February 10, 2014 at 5:53 pm). The report is for UK academic researchers – the term professor is used differently in the UK to the US (again as discussed in comments above), so the figures may look very different from your experience if you are considering this from outside the UK. Our (UK) understanding of what a “professor” is, is different.

However, the key point of the article is universal – as you start on the academic track, be aware that there are fewer opportunities to be a permanent member of academic staff than you might believe; start exploring career options early (as Plan B or Plan A) and take opportunities to develop a broad skill set. Whatever the precise numbers affixed to each arrow in the diagram (and you’ll see above I know at least one is wrongly labelled), the diagram is a powerful tool for getting researchers at any career stage to “wake up and smell the coffee”. When I use it, I encourage people to react by finding out what the reality is in their own field or institution and to start asking questions to determine if they are on the career path they think they are.

I’m grateful to Athene for posting her views on this – I’m going to use this blog post in future workshops with researchers, particularly the ten very powerful questions.

Perhaps it depends on the department and the sub-discipline.

I recall going for interview for a PhD studentship in fundamental theoretical physics at a good-ish university in 1989: the group of applicants was told by a senior scientist that very few of us would make it to permanent academic positions, and we really should not embark on a PhD in the expectation of doing so. It was rather dispiriting.

So I went to Durham instead. There, if I have recalled correctly, six out of seven of the students in my and the two preceding years are now academics.

It is interesting to see the different perspectives here, but one point that I think is important is the notion that supervisors should do more to help students consider their future career options. Of course they should, but we should not entrust it solely to them.

At Sheffield we require a second supervisor to monitor their training and wider skills in the context of not just getting a PhD, but also for the implications in a broader range of career paths.

Students need to be encouraged to think about their future. I note one comment above stating that students do think about the future, but in reality not enough do to the fullest extent required. In 2014 a student should have a portfolio – a document – of skills and the ability to articulate those skills. Many universities have the software required to complete a portfolio. The ability to understand the wider benefits to what might be perceived as a very narrow training is particularly useful. You might be the only person in the world to be using a certain piece of kit, but that’s because you created it!

Secondly, making a decision about what you want to do and then deciding about how you would go about achieving that goal is crucial. Therefore being part of networks, student societies, and the like are all very helpful for understanding how to get there. If the goal is a certain industrial sector, and you have had several years of finding out about the sector and making contacts, then you are more than half way there. If you don’t know, start at your careers service! They won’t tell you what you want to be, but they will tell you how to find out about the options. This might seem like an inconvenient drain on your time, but it will pay for itself.

I don’t think terrifying is the word that I should use to describe this part of life. The uncertainty is exciting. I decided I wanted to be an academic in year #3 of my PhD and from then on, I was very careful about what I chose to do. Each person has their own way to achieve their goals, and their circumstances are different. My view of overseas postdocs as having been right for me is fairly standard, but we need to improve in how we view those whose career development is less mobile, for example, for family reasons.

Anyway, the variety of your posts remains to give pleasure. You are not the only one to eschew travelling light, although I feel slightly less neurotic on reading your post on the matter!

The sentiment of your post – that early career researchers and post-docs need to reject the notion that “anything outside academia is Failure, writ large” contrasts with the language used to describe the process of weeding out the presumed non-failures. The unsavoury fact is that part of the permanent academic job is to kick people out because only a mere 0.45% ends up making the grade – but those people weren’t failures.

Science is only tenuously economic. There are too many people chasing too few financial resources to carry out research. The economic reality is that ‘the system’ needs most people to ‘fail’ or at least leave. That reality needs to be spelled out very clearly to incoming PhD students.

Why do people at the early and middle stages of the pipeline view things outside academia as failure with the capital F? I suggest it is because the timescales over which permanent appointments take place mean that almost unavoidably, anyone who is destined to be kicked out is subjected to six months to a year of being treated like garbage before being unceremoniously let go – why waste scarce resources on people whom senior management have already decided to discard?

If only academics were brave enough to tell someone to their face that it would be better to look elsewhere for their future. In reality, I’ve witnessed that such discussions are normally held down the far end of a dinner table at a group meal, to much merriment amongst the permanent staff, whilst the post-doc or PhD concerned is located at a vantage point from where (s)he can overhear the snippets but is not involved in the discussion. Senior academics then brief their PhD students against their pre-kicked post-docs, encouraging them to steal their time; and to treat them as exploitable resources to the greatest extent possible. The post-doc is typically put on a totally meaningless project with no research value (witness the DPhil who moved to a London University for a post-doc, to be asked to solder together a laser safety interlock system – a GCSE electronics project – which was completed and handed over to a new PhD, then, oops, a month later, goodbye post-doc)

Athene Donald may well be the exception that proves the rule – she recognises that she deals with people and therefore she decides to treat them with a modicum of civility – if so it’s commendable but it’s far from common practice.

The reason that academia enjoys government subsidy relative to other industries is because it claims to be able to to generate and synthesise valuable new knowledge, whilst providing valuable skills to even the temporary workers passing through the pipeline. Yet, when I asked my university about the destination of post-docs leaving academia at one of our skills sessions (incidentally given by a former post-doc who then got a role as an careers advisor discussing how to leave academia) I was told that no record is kept about the career trajectories of the kicked following the kicking; presumably because it does not matter to the University where the rocket comes down – I think it should matter.

My own admittedly anecdotal sample of watching the fates of post-doc colleagues suggests that those kicked out spend typically six months unemployed, and that the terminal stage in the academic pipeline is rather demoralising – my Chemistry friend took to absenteeism on any day her direct report was out of the building, because she hated her direct reports predilection to humiliate her in front of the PhD students – meanwhile of two theorists who were also contemporary, one took 6 months to find other work, and the second is still unemployed. Essentially the impression most of the kicked receive is that they’re contemptible individuals; The sense of failure that comes with being made unemployed is not solely the result of unrealistic academic aspirations and a stubborn refusal to go quietly. Being kicked out (made unemployed) is a real frustration that strains family and any romantic relationships.

A six month spell of unemployment for a kicked-out post-doc could easily cost £15K of income to the affected individual and ~ £4K to the government in lost tax revenue. For economic reasons alone it would be worthwhile to invest coherently in outplacement, and to measure outcomes for the (26.5) / (26.5 + 3.5 + 0.45) = 87% of PhD graduates and post-docs whom we already know will be eventually deemed to have missed the grade. Financial penalties are already imposed on departments whose PhDs take too long to graduate – the same should be true of departments whose kicked remain unemployed following their firing.