What a rubbish year this has been, on different fronts. We are in a far worse state than could conceivably have been imagined this time last year and, the start of vaccinations apart, there is little light visible to cheer us up over our rather solitary – given last minute Government instruction – Christmases. However, I was set off in an unexpected direction yesterday, by a tweet, which distracted me for a little while from the gloom and doom.

The tweet took me to a brief video montage (which can be found on You-tube) of passengers at London railway stations in the 1950’s and ‘60’s. The London in which I grew up; the stations I occasionally got taken to, in order to meet family or to head off to see them. These sights from the clips seemed very familiar (although I don’t think I ever went to Fenchurch Street). There were some striking observations:

- The pollution. It is easy to think ‘nostalgia’ when thinking of steam trains, but stations were filthy places. The grime of a Kings Cross or St Pancras has long been swept away by generations of modernisation, but the air must have been foul. But then, these were the days of pea-soupers, so probably it all seemed quite natural. I certainly remember regularly walking to primary school in thick fog, and also returning from one summer holiday to find the coal fires had been replaced with gas, sometime after the 1956 Clean Air Act.

- The clothes. A woman in a most peculiar hat particularly struck me, probably because I feel I can remember my mother in something very similar. However, most women I spotted with something on their heads in the videos were wearing headscarves, something else my mother certainly wore, as I did too, up till I was in my early teens, I would guess, and discarded them. No woolly ski hats common yet for men or women. I was surprised how few of the men were wearing hats, trilby’s in particular, no doubt because both my father and my grandfather always did, so that it seemed ‘normal’.

- The (lack of) health and safety. In those days many, possibly most, of the trains had carriages for 8 or perhaps 10 people, with doors that opened straight onto the outside world, although increasingly designs were changing so that they led into a corridor running along the length of a carriage. Doors that could be opened simply with a handle, no waiting for the driver to press a safety switch once the train had come to a complete stop. Consequently, the clips showed many passengers had doors open as they came into a station and people alighting while the train was still moving.

On London buses, likewise, one could hop on and off when in motion, and passengers did just that frequently. I can remember a school friend turning up at my house bruised and battered having fallen down when they timed that wrong. Even worse, I can remember opening a door of a train (when returning to Cambridge from London, so this would have been in the early ‘70’s) expecting it to be into a corridor, only to find it went straight outside. The train was going at speed. Luckily, I got myself in again safely and managed to pull the door shut, or I would not be writing this blogpost. Another passenger helpfully remarked I needed to be more careful, but otherwise I don’t remember much alarm being expressed by anyone, myself included. Health and safety gone mad is a useful derogatory phrase, but sometimes there is some point to it.

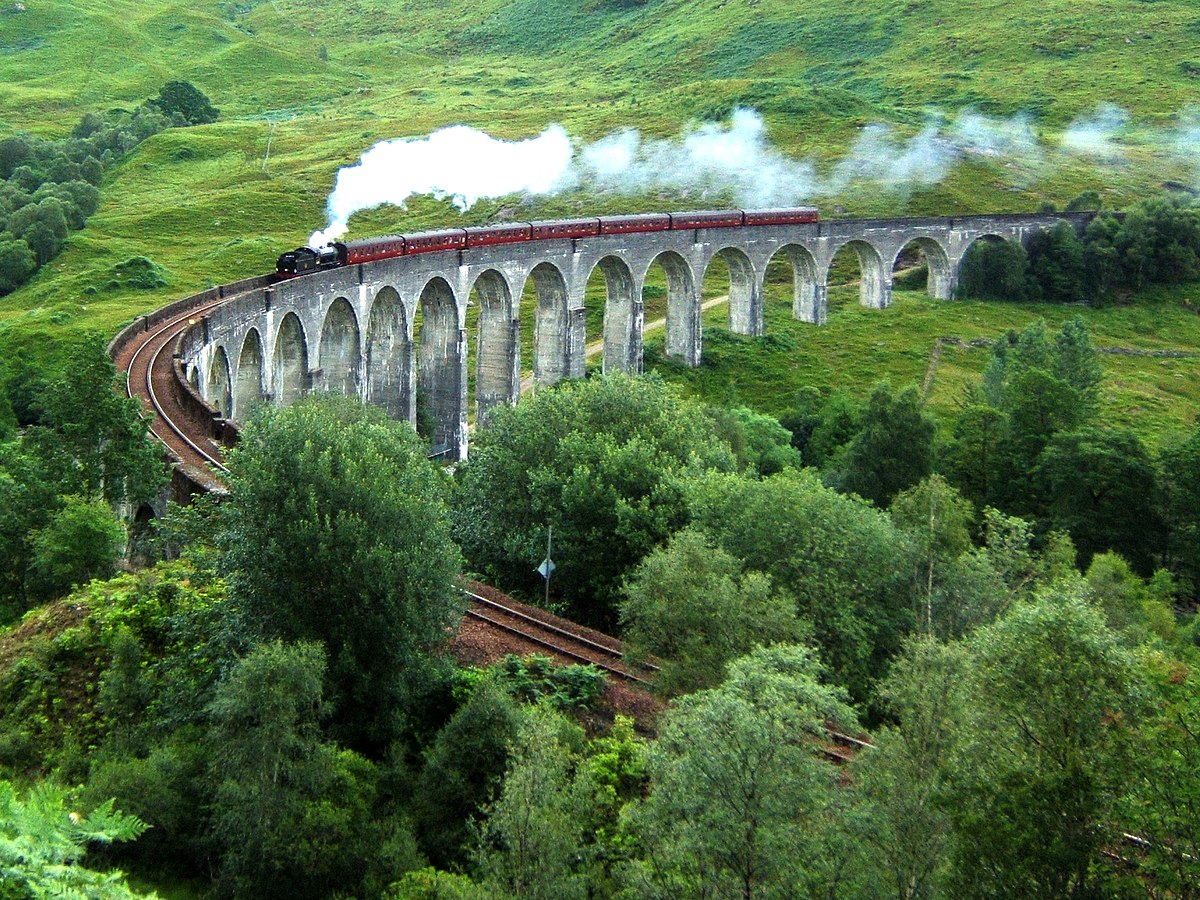

But of course, once one starts reminiscing and looking things up on Wikipedia (prompted, in this case, by that video) inevitably memories take one into strange places. Steam trains – Hogwart’s Express – Glenfinnan Viaduct, where the iconic footage was taken for the Harry Potter films, as well as the photograph shown here – and hence to memories of several holidays in Glenfinnan in the early-mid 1960’s. There I can visualise my father and grandfather, of course in their trilby’s providing little protection against the endless rain, my mother and I in headscarves (but not, I think, my sister). No steam trains on the West Highland line by then, it was diesels between Fort William and Mallaig, a trip we would make regularly. The line was single track – just as was the so-called ‘road to the isles’, with infrequent passing places making for hair-raising trips by car – and I was fascinated by the ease with which driver and station manager would exchange tokens between platform and moving train to demonstrate the line ahead was clear and safe to enter. Was I thinking with my nascent physicist’s mind about relative velocity when watching this transaction? At 10, I rather doubt it.

I have vague memories of a haunting story of a horse and cart falling into a pillar of the Glenfinnan Viaduct during construction. In my childhood memory I associated a man driving that cart as falling in too. A quick Google shows that the story in outline is true, but in fact it did not occur at Glenfinnan (but at the Loch Nan Uamh viaduct nearer Mallaig) and no man seems to have been involved. The wonders of careful scientific experiment in 2001, using radio waves to penetrate several feet of stone, managed to locate the horse’s skeleton and so corroborate the basic story.

Occasionally, returning from a day out in Mallaig, we would indulge – at the exorbitant sum of 2/6d, if I recall correctly – in sitting in the Observation Car, a great treat to give us panoramic views of the hills, perhaps the occasional deer or buzzard (however hard we tried to turn them into golden eagles). Rhododendrons had not yet taken over the hillsides. However, that is inaccurate. We took the train to Mallaig, not to spend the day there walking around smelling the kippers, a key industry at the time (sorry to mention fish at this delicate time in Brexit negotiations), but to catch boats to the Inner Hebrides. As far as I was concerned, the rougher the weather the better in these little vessels, although lashing rain could make it unpleasant and hard to focus on the birdlife we wanted to look at.

Twitter is a wonderful way to waste time, useful though it can also be, not least because of all the rabbit holes down which one can disappear, on this occasion prompted by that cliché Memory Lane. Still, we need good memories to get us through the current darkness and so I shall hold on to them while I wait for life, eventually, to return to something one might imagine one could call normal.

Observation car.

During day, counting animals, stations with an OS map and a magnetic compass (the sun is not always shining, and to a child– not always due south.)

Night. Looking at bright stars, lights in houses, and marking off (with a yawn), stations on the OS map.