The end of this month marks my retirement from my professorial position at Cambridge, something that I still find rather surprising. My career on that front has just faded out, yet another victim of the pandemic; the conference planned for the week just past to celebrate my career, bit the dust a long time ago. There is absolutely no rite of passage, other than (mistakenly) being sent an ‘exit questionnaire’ asking me why I was leaving. When I pointed out that this was pretty inappropriate, I then found myself having to negotiate the status of my university card to enable me to get – eventually – back into the department. Pandemic past, I will need to sort out my office. This all feels a sad end to 35 odd years working for the Cavendish.

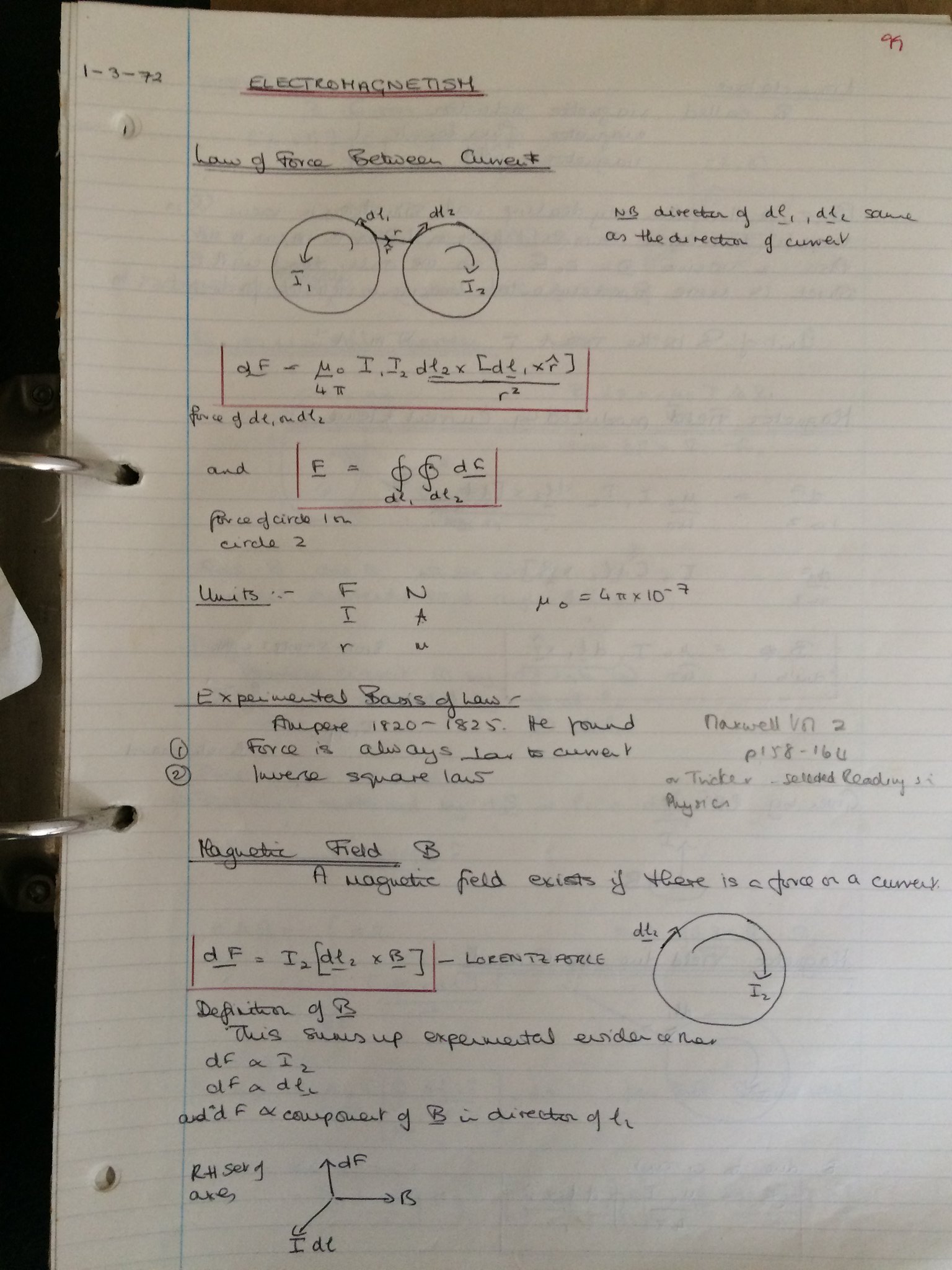

Of course, my life won’t change radically. I continue as Master of Churchill College, with a somewhat increased notional time allocated; I will continue on the various committees I serve on for different bodies, writing my blog and so on. My research group had slowly been winding down anyhow, with my last PhD student being awarded their degree in February. This year’s bizarre examination season – a mixture of virtually-conducted vivas and online papers to mark was my portion – will be the last I ever have to wade through. What should I do with all my own (hard copy) notes on exam setting and lecture notes? The latter include both those I personally took all those years ago, and those I have given, or at least those I gave up until the advent of everything being done via Powerpoint. I cannot believe the beauty and neatness of my own lecture notes, as evidenced by the photo; my handwriting has deteriorated a long way since those heady teenage years. I chose that image because Electromagnetism was the first course I myself taught some dozen years later, and with an identical syllabus. Those lecture notes of mine came in handy….

It is strange to look back on what has changed and what really has hardly budged at all. The proportion of women taking physics in their final year in Cambridge has perhaps doubled, from around 10% to a little over 20%. The number of women on the Physics staff has, however, mushroomed. From my appointment in 1985 as the first lecturer (imperceptibly pregnant) formally on the staff, to now, the change is remarkable: after I retire there will be four female professors, two readers and six lecturers, plus two other women who hold joint lectureships between physics and another department. There has yet to be a female head of the department (not for want of trying on my part). The department currently holds a Gold Athena Swan Award although, given the bonfire of bureaucracy I wrote about previously, will they bother to continue? I hope so, but I am deeply concerned about Athena Swan’s future.

Looking back from a position of undeniable seniority, it is sobering to realise that at one point I was so miserable, over a number of years, that leaving Cambridge seemed the only sensible thing to do. As an interdisciplinary scientist surrounded by purists, as a woman leading a burgeoning group yet whose voice never seemed to cut it, my mid-career years had some really dark moments. This, note, was when I was already a professor and an FRS. As I discussed this week with Anne Glover – former Chief Scientific Advisor to the President of the European Commission – in advance of our (recorded and soon to be available) public Conversation, mid-career can be every bit as hard as the early years for women and even, at least in both our cases, worse. That moment when you become a player but equally an alien threat, clearly bothers some men.

When during my unhappy years, I described my interactions with one particular colleague to a friend, he shrewdly remarked that the professor in question probably didn’t know whether he should interact with me as if I were his mother or his girlfriend. That felt about right, after I’d had to chair a committee (I was deputy head at the time) and this guy had publicly berated me but then privately asked me afterwards if what he had done, in another part of the meeting, was OK. I suspect I just grunted at him at the time. Now I would have the luxury of greater confidence enabling me to be a bit more explicit about my view of how he had behaved.

I was fortunate in the support I received from other colleagues, both senior – such as Sir Sam Edwards and Archie Howie (who also happens to be a founding Fellow here at Churchill and very much still active) – and more junior. To keep going when it feels like your head is continuously hitting a brick wall, is hard. My research was always rewarding (if often frustrating), and I loved moving from topic to topic. Maybe I did this too much, but for me that was how I got my kicks, something I described in a relatively early blogpost. It is something of a cliché to say that it is the people who make your job worth doing but, just as there are those who make life miserable, those students and postdocs who challenge and stretch you are immensely satisfying and mind-expanding. But, equally, the students who start off slowly but blossom as their research progresses – ideally, but not always, because of your own input – are a pleasure to watch and to interact with.

Even those students who are most difficult to deal with, for whatever personal or scientific reason, bring their own reward as they finally sail through their vivas: I have never had a student who failed their PhD, although I have had a handful none of whose work ever saw the public light of day in a publication. And, in at least one of these cases, it was because every experiment they tried – and there were many, this was not in any sense a lazy student – came up with a null result. These days one could have posted such negative results on a preprint server to demonstrate that, despite differences in production of the particular material (chocolate!), none of the physico-chemical tests we attempted showed an iota of difference; back then it was formal publication or nothing.

People ask me what got me through the difficult years. Obviously I owe much to my supportive colleagues (not to mention my husband) who listened to my moans and gave me advice. Often the advice was to leave and go elsewhere. To a large extent the reason I did not go was my sense that if I went – and some encouraged me to go citing constructive dismissal, although I’m not sure how well that would have worked out in practice – I was letting down all the women who would come after me. If I couldn’t stick it out, who could, was my fairly conscious thought. It felt important to weather the storm in which I felt engulfed. Ultimately, I am sure that was the right thing to do. But I did get angry and, in due course, this anger led to me getting involved in the issues facing women much more explicitly. That deviation from the purely scientific in due course gave me a voice that was taken seriously within the University when, as a scientist, it seemed I frequently was not. Accidentally, I found an alternative path to being able to make a difference.

Others said, even at the time, “it doesn’t look as if you’ve done so badly”. Fair enough. As I say, I was both a professor (at a time when this was still a Cambridge rarity) and an FRS. But the frustrations were real. I found it bizarre that I was taken much more seriously outside Cambridge, including at the Royal Society even as a newbie FRS. That gave me confidence that it was something peculiar to the Cambridge of the time. As I head off into (semi-) retirement, I hope the current generation of mid-career women find a much more supportive environment in which they can thrive, whether in their science or in their wider contributions to the community. That their voices are heard, without the need to raise them, and that obstacles are not put in their way because people find them different from the male-by-default attitudes I suspect I faced in my day.

Comprehensive and inspirational but succinct, as always. Thank you.

I am from your generation, and I couldn’t take the hostile environment in the professional field in which I was interested. Which of course is OK as I waged ‘good trouble’ (per John Lewis) in other ways. And I will continue until I drop. The potency of women’s anger has been and still is grossly underestimated by those in power.

Wishing you a long and happy retirement. One that is productive and busy, because I doubt you’d enjoy it so much if it wasn’t. I have followed your career with great interest, and in many ways little surprise, because of your brilliance as a small child. There are many people, specially women who can’t live up to their early promise. You did, and did your best to make it easier for women following your footsteps. I hope you do not give up the blog, I have apprectiated your witty, ,thoughtful, honest voice.

Thanks Jane. You must have known me longer than any other reader of my blog, even if we haven’t met for 50+ years! Certainly we were friends in junior school, though I’m not sure about infants. I’ll keep going with my blog, as long as I think I have new insights to offer. Did I ever tell you I met your mother at New Hall (as was) once – but she only remembered my sister, probably for all the wrong reasons from school.

Echos my experiences to an extent!

Wishing you a Happy and Productive Retirement

I hope you enjoy every moment of your retirement. I was fortunate enough to be lectured by you (Part IB Physics I think…) and you remain one of the outstanding lecturers of my time at Cambridge (in the mid-nineties). I’m not sure if we ever actually spoke directly (I think not) but even from the front of the lecture theatre you gave me confidence that aspiring to be a physicist was not unreasonable for a woman. And here I am, FInstP, knowing that that confidence was justified. Thank you.

We have never met, and I am not a scientist (though my published work rests solidly on scientific literature). We have Cambridge in common, as I was a student there from 1975 to 1984 and completed my PhD successfully in January, 1985. I loved Cambridge (to which I repaired following a successful career at Oxford), but also found it enormously intimidating. I retired from academic life six years ago and find retirement satisfactory: plenty of time to do research and publish, and no committee meetings to go to, no papers to grade, and no campus politics to fight. I saw a lot of horrible things done to people during my academic career, including abuse of several female faculty members. I am wondering how much the academy suffers from really deep systemic dysfunctions of various kinds, and whether the problems you had to overcome as a woman in science might owe something to those deeper pathologies. Something perhaps to think on and write about in future.

Best wishes from Canada.

I’m sure part of the problem is the competitive nature of academia. Too many people see it as a zero sum gain, so one person’s gain can only be another’s loss. They lose all sight of the person themselves and inbuilt incentives reward that behaviour. Changing academic values – so that bigger does not mean better for instance; I’m sure I’ve written about that before – would be needed for real systemic change. I’m not holding my breath for this to happen any time soon.

This is the first of your blogs that I have read but as a senior female academic who felt “unheard” during the middle years, your post resonates. Thank you so much for detailing it as I think it still impacts on female academics in their middle years. I do hope you have a productive and happy retirement (and I am sure you will not miss that administrative part of academia that comes with an extra layer of competition that is surprising when amongst it but represented well in fiction and part of human nature – humans are very competitive).

Just noticed you are retiring and I hope it goes well.

Although I was not in the Cambridge bubble you should know that I heard and appreciated your contributions throughout part of my (lesser) career and I know that you worked hard trying to help at that time – so thank you.

Thanks Gary. Those were interesting times in Norwich. I hope all is well with you.

It is truly unfortunately that the circumstances of the last 6 months have resulted in your quiet departure from the Cavendish after all the years of wonderful service. I am sure the department would have liked to do much better than that if it had been possible. You don’t know me, but I have observed you from the distance since I arrived in the department 21 year ago. Just know that you have been an inspiring example for women in physics and that you have made a difference. My best wishes on your ‘semi’ retirement and your continuing endeavors as Master of Churchill College

Thanks Patricia. It is fantastic that the number of women at the Cavendish has grown so substantially. I know how much role models matter and I am sure you will be fulfilling that both in Physics and at Lucy Cavendish.