As a physicist, I may enjoy reading popular history books, but I don’t expect to get involved with history. Coming to Churchill College has given me a wonderful opportunity to learn more about the Archives here and how they are preserved. I enjoy meeting those scholars who come to spend time here. Scholars such as Graham Farmelo, who used the Archives extensively when researching his book Churchill’s Bomb, as well as more formal academics, whose research may not be seen by the general reader. However, the College’s Archives, set up to house the papers of Sir Winston himself, are a treasury of twentieth century papers and, to a lesser extent, objects. The most recent of these acquired is the late Tony Hewish’s Nobel medal, but they also include more mundane items, such as a Maggie Thatcher handbag to go with her archives. (As the photo shows, I wasn’t allowed to touch the bag, which is kept carefully sealed.)

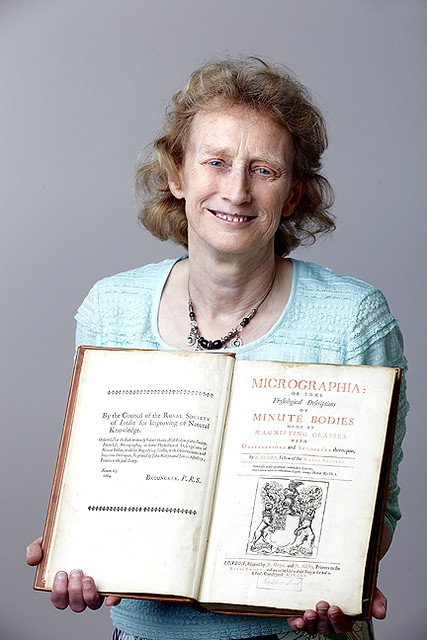

However, having been born in the middle of the twentieth century, much of the collections held at Churchill don’t really feel like history. After all, I remember Maggie Thatcher’s premiership well; I could even tell you where I was when I heard she’d resigned – announced over the tannoy system in Boots in Cambridge. So getting close to history, to me, means going further past. In the past, when previously a member of the Royal Society’s Council, I had an opportunity to get my hands, literally, on Robert Hooke’s magnificent book, Micrographia, as shown, but no chance to examine it in any detail. As a microscopist by training, I’d have loved to look closely at his drawings, which (reproductions show) are mind-blowingly detailed and beautiful. I’m sure I’d never have made the grade as a microscopist if I’d had to draw everything, as opposed to being able to photograph it, be it via the light or electron microscope.

However, last week I had a fantastic opportunity to get my hands on some roughly contemporary books, and really to look at one in particular in detail. This opportunity arose to allow me to follow up on the information I’d been sent, during the pandemic and via photographs only, about Mary Astell, about which I wrote previously. Mary Astell (1666-1731) was a natural philosopher, mainly known as an early feminist, who wrote a book advocating a college for women (A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, for the Advancement of Their True and Greatest Interest, published anonymously in 1694). She believed that women should be encouraged to look beyond mother and nun as ‘career’ alternatives, but her plans for a college came to nought because it was viewed as potentially papist.

However, it turns out that she had a penchant for the study of science. She was brought to my attention by Catherine Sutherland, deputy librarian at Magdalene College in Cambridge, who has discovered in the college’s collections, a number of her books. The one I got to examine in detail was Les Principes de la Philosophie de Rene Descartes, a French edition of the original Latin text. Astell has made numerous, and at times extensive, annotations across the text and on the end-notes, where there were additional copies of the plates in the book. Many of the annotations were in pencil, and often hard to read, but these seemed frequently to be aids to her own translation or, at times, her objections to the words Descartes used (she seemed particularly to object to the word subtile to refer to astronomical objects, replacing the word with celeste, probably relating to her own religious beliefs). At other times she was writing out her own thoughts on the text, as a student today might do. Sometimes these were written in pencil and then clearly over-written subsequently in ink, presumably once she’d got confidence in her arguments. In other places it seemed she’d gone straight in with her quill. Her writing was small and, even with a magnifying glass to suit my elderly eyes, I had trouble always deciphering what she’d written.

Since my ability to read Descartes in French, published with the ‘long s’ (i.e the one that looks like an f without the crossbar, used in English printing as well at the time) is distinctly limited, and it is not a book I have ever studied even in English, it was hard for me always to follow her arguments and check she had mastered what Descartes was saying. But it was absolutely clear how much effort she had devoted to getting to grips with the books. The notes at the end were extensive and thoughtful and, at times, she indicated that she felt there were errors in what was said.

Spending an hour looking through the book was a treat, even if also frustrating. Frustrating, because it clearly needs someone much more familiar with the history of science, the science as it was understood at that time, to examine the annotations and to put them in context. How much could she have learned from the circle in London in which she moved as a distressed gentlewoman (she seems to have relied largely on financial support from richer women who she had got to know)? It is known she spent some time working as an assistant with John Flamsteed at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, but it isn’t obvious whether the annotations in this book pre- or post- date that period. Did she know any, or indeed many, other natural philosophers who would have engaged in their discussions largely at the Royal Society, a place she could not enter? It strikes me the books held at Magdalene and recently discovered would potentially provide the basis of a fascinating PhD in some interesting interdisciplinary way. Maybe someone will follow up on this.

I am deeply grateful to Catherin Sutherland to have enabled me to have this morning of exploration, opening my eyes to topics so far from those I usually tangle with.