Even though I initially trained as a virologist, it’s a little known factoid that I did my PhD in an old-fashioned Microbiology department – back in the days when “microbiology” really meant “bacteria”. We virologists populated a small unfashionable pocket in an otherwise seriously old-school establishment. From the array of teams working on microbes as diverse as Agrobacterium and Salmonella to the annual Christmas pudding steamed in a 50-liter container in the main autoclave, it was an all-singing, all-dancing floor of no-nonsense bug work.

To earn my upkeep for the first year, I had to teach large labs of medical students the rudiments of sterile three-zone streaking, Gram stains, blood agar and the IMViC coliform test. (For some inexplicable reason that none of the professors could explain, the E. coli residing in my gut were reproducibly indole-negative, so I couldn’t use my own commensals as a classroom control. Considering how these are traditionally isolated, I considered it a bit of a blessing.) Although my heart belonged to the Retroviridae, I took great pleasure in the rituals and manipulations of classical microbiology and passing these on to my students. Even today, I still use the three-zone streak method and a flamed platinum loop to isolate colonies for cloning, even though most of my colleagues just scribble bugs with a dirty yellow tip and do just fine that way. It may not matter for molecular biology, but it’s more about taking pride in the proper way of doing things.

So, two decades on, it’s good to be back in a Microbiology lab with a capital M. Although I’ll be working on the cell biological aspects of urinary tract infections, there is a significant component of pathogen investigation that we need to do in parallel. Things have definitely moved on since the IMViC test: we now have fancy test strips to assay for indole production and the other metabolic readouts used to distinguish similar bugs from one another – and the most amazing chromogenic agar, onto which you can streak an unknown mix of bugs and separate out strains in a rainbow of different possible colored colonies.

But amongst the high-tech kits, relics of our deep microbiological past lurk high on dusty shelves. I’m sure they’ve never been thrown away simply because they’re too beautiful. And I’m certainly not going to break that tradition. So we’ll keep working in the shadow of a more genteel past, harking back to an era when things were made of glass and tooled to precision specifications by craftspeople who took pride in the aesthetics of their products.

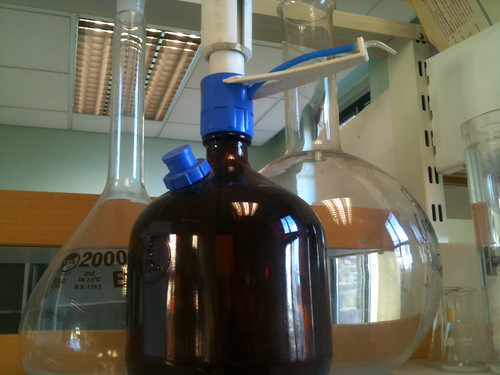

But I’ll close on a mystery: what the heck is this?

It looks like a weird pint glass, but its curvature suggests that the opening is meant to be facing downward. It rather harkens back to the days of Joseph Priestley, who put glass jars over mice to see if they required something in the ether to survive. But I suppose it might also just be an over-engineered Bunsen burner snuffer.

All ideas welcome!

It’s a Kwak glass, innit?

Ooh that takes me back. Mine was in lipid chemistry and I lived in glassware and solvents really 😉

I’m trying to remember what it was I used the brown glass bottle with the pump bit for… I think it was to add something noxious to something else… possibly to do with a scintillation counter.

No idea what the glass lid or possibly mixing bowl thingy is at the end though. I’ve used enough round bottomed flasks in cork stabilisers to appreciate that it could go either way 😉

Is it for creating a microaerophilic (or anaerobic) environment? (you cover petri plates with it?)

I’m not convinced you’d really block all the oxygen without a seal (although if it was good enough for Priestly…).

“The shadow of a more gentile past…” made me laugh. I imagine you meant “genteel”, unless I’m missing something very clever indeed.

Apart from a snuffer, the only thing I can think of is that your mystery glass is supposed to sit in a retort stand (like a round-bottomed flask), but I can’t imagine what it would be for. Boiling up hot chocolate, perhaps?

Oops, thanks for the correction, Winty.

Hot chocolate….on the chromogenic agar, E. coli is very nicely hot cocoa-colored.

“Hot cocoa-colored” sounds like a euphemism for “sh*t brown”, which would be about right for E. coli I think. 😉

I took a microbiology class… a long time ago. I remember doing some color tests, and using blood agar plates. It seemed like a fun kind of magic.

I too did my time as a microbiologist in my first postdoc; investigating virulence determinant regulation in Staph aureus. I too maintained my platinum looped streaking habits later on even when doing routine molecular biology. There’s a right way and a wrong way you know! Thankfully we never had “rainbow agar” as I’m not sure my colourblind vision would have coped with it. I have enough trouble with red/green fluoresence, let alone teh subtelties of pH strips or chromogenic agar.

As regards your mystery glassware, isn’t it just a fancy bell jar with a handle? Or it could be a cunning pint glass to make you drink quicker as you can’t put it down on the table?

Looks like an anaerobic jar. You put the culture in with a candle. We had similar ones but they also had a tight fitting base.

As an undergrad working in a B. subtilis lab, I always liked those sidearm “Klett” flasks – though washing them was a pain in the rear. My father, a biochemist, keeps a collection of tiny lab glassware (adorable Erlenmeyers! baby beakers! pixie pipettes!) as a display in one of those glass-topped coffee tables, in the living room. Science geek family is geeky.

I still use a flamed platinum loop and the three-zone streak method; official policy is that we’re not supposed to have open flames in the lab, but I keep a couple of small alcohol lamps around nevertheless. Some things require an open flame: the aforementioned platinum loop, the tungsten wire that I sharpen for microdissection instruments, and fire-polishing glass pipette tips of various dimensions (to pick up microdissected pieces, or to triturate ganglia into single-cell suspensions). I also pull flame-softened glass pipettes apart and burnish the tips, to make tiny scrapers to remove the epithelial component of pharyngeal arch or neural crest/neural tube cultures. Fire is a necessary part of humankind’s tool-making efforts, and I refuse to give it up! 🙂

I like the sound of your tools, Kristi!

Also, an oft forgotten fact is that a lit burner on the bench keeps the air moving upwards, which helps prevent contamination of open plates when environmental bugs drift downward. Also, if you religiously flame the mouths of your broth bottles, they can keep forever without being contaminated.

Ah, an anaerobic jar with a candle – very clever. Without a seal, will the oxygen leach back in eventually? I can’t remember if the edge is flat or curved.

Those are separation flasks (funnels), glass stoppers and glass appartus to run columns with – think inorganic and organic chemistry! I’ll take waht you don’t want! lovely!

and the most amazing chromogenic agar, onto which you can streak an unknown mix of bugs and separate out strains in a rainbow of different possible colored colonies.

oooOOOoooh. Photos please!

You’re beginning to make me wonder if my undergrad training was old-fashioned – we learnt the flamed loop and the three-zone streak stuff. This from a computational biologist who hasn’t done ‘wet’ work at Ph.D. level 😉 (My undergraduate was split between the microbiology and computer science departments.) The middle photograph definitely reminds me of chemistry lab classes!

“an oft forgotten fact is that a lit burner on the bench keeps the air moving upwards, which helps prevent contamination of open plates when environmental bugs drift downward.”

My lab still did this when I left in 2008. I don’t think it’s forgotten. Not in biochem departments anyway.

Photos of chromogenic agar will be furnished in the next blog post…not for the faint at heart. Meanwhile, apologies to Ian and color-blind folk everywhere. Ian, you’d be happy to know that one aspect of old-fashioned bug identification we still use involves sniffing the plates!

Pretty sure my streaking technique is the “three-zone” method, although I don’t remember it ever being called that, just “the way to streak to single colonies” or some such gibberish.

Sniffing the plates – eurgh. I remember this too, as a good way to tell if something was contaminating good old coli plates. I can’t remember what it usually was though – larger white colonies that were sort of wet and shiny looking, and distinctly stinky. Some kind of Streptococcus maybe?

Jennifer, as far as I know the slight vacuum created by the candle is enough to seal the jar onto a smooth surface – I think they used a piece of glass and maybe some grease around the edge. The ones I used had a glass plug with a rubber seal – like an upside down kitchen jar. After those we used plastic jars with palladium catalysts and now we use full anaerobic incubators with constant atmosphere, humidity and temp. Ah progress!

“Also, if you religiously flame the mouths of your broth bottles, they can keep forever without being contaminated.”

In my old lab we obviously routinely flamed the neck of most bottles. after all, if you work in a microbiology lab, you shouldn’t be surprised at the amount of microbes floating around. One time a postdoc was making up his antibiotic agar plates and flaming away as he did it. He was making plates containing chloramphenicol, the stock solution of which is made up in ethanol. He flamed the neck of the falcon tube containing his chloramphenicol a bit too enthusiastically/carelessly and set fire to his stock solution! A moment of surprise and panic, probably as he snapped out of the daydream you sometimes get into in such a routine task, meant that he dropped/threw the tube out of his hand onto the bench. Of course this just meant that the flaming solution poured out over his bench melting polystyrene tube racks etc as it went. The postdoc then grabbed his lab coat (thankfully he wasn’t wearing it or he’d never have been able to swing it properly) and beat the flames out with it, proving that a lab coat really is a useful peice of safety equipment. The safety inspectors did a double take on their next inspection when he walked past in a lab coat with big scorch marks on it though! True story.

Obviously a rank amateur.

My supervisor managed to knock over a bottle of 70% in a flow hood and burn down the cell culture room.

On Christmas Day.

I love you guys.

Those are excellent stories. Much better than my attempt, which was boiling over a solution of 20% SDS onto a hotplate, filling the lab with evil-smelling smoke and necessitating a prolonged lunch break while it aired out. Thank goodness there were no smoke detectors.

P.S. Jenny, I’m sure* your future techs and students will be much more reliable.

*mostly

My lab partner during undergrad once set fire to our little beaker of ethanol too, and had to put it out with a lab coat. Our prof told us that made us real scientists.

My own moment of glory came due to some residual nerve damage in the arm I broke as a kid. I was holding an open 2L bottle of conc HCl in my left hand, and had one of the weird spasms I used to get occasionally (like, once or twice a year) when all the muscles in that arm would just suddenly go floppy, causing me to drop whatever I was holding. I jumped back as the acid splashed up over me, pulling off my lab coat and gloves in one fluid movement and throwing them across the room. Not a single drop touched me… but when we got the all clear to go back into the evacuated lab about an hour later, there was a HUGE acid scar on the floor that’s probably still there to this day, and holes all over the left arm of my lab coat. The material in the elasticated cuff had somehow fused with the glove into a big plastic blob… hooray for strict safety regulations in that department, which I’ve continued to observe even when in somewhat laxer environments!

Cath’s story reminds me of a fellow PhD student in our lab in Edinburgh (many years ago) who poured water into a measuring cylinder of conc H2SO4. The resulting minor explosion doused him waist down with a liberal quantity of acid which within seconds began to eat holes in his jeans. I can still remember him walking home that day wearing his lab coat, bare legs, and a bin bag containing a few fragments of denim.

Yikes. How did he get to PhD level without learning that one?

Now you mention it, I don’t think he ever wrote up his PhD, and he certainly gave up lab work a long time ago.

Well, a lucky escape there, I think.

I’ve got a couple of phenol stories, but they actually scare me so maybe I’ll save them for the campfire.

can you stop scaring Jenny ! (and me for that matter)