In mid-November, a journalist from BBC Southeast contacted me about a perplexing rise in COVID-positive cases in the nearby borough of Swale, a mainly rural part of Kent known for its fruit orchards, beer hops and vast areas of marshland within the Kent Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The borough is dominated by windswept fields and open land dotted with the occasional factory or wind turbine – isolated and underpopulated. As the journalist remarked, it seemed an unlikely place to be incubating a mass of new infections compared with its mighty neighbour, London.

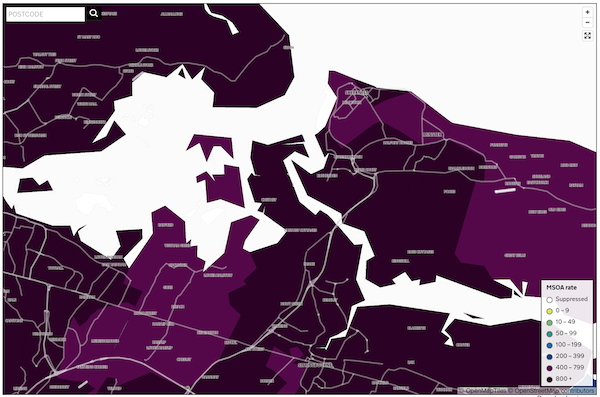

But incubating it certainly seemed to be. He quoted a concerning figure: at the beginning of September, the rate was just 6.7 cases per 100,000 people, yet it now stood at 531. The epicentre seemed to be the Isle of Sheppey, which protrudes out into the North Sea, separated only by the swathe of water that bears the borough’s name.

Later on, after pouring over the most recent maps, I speculated to the presenter on air that perhaps the surge was connected with the commuter belt, as it did seem to hug the High Speed 1 rail line all the way down to Ashford. But that didn’t entirely make sense – if the source were London, then why wasn’t London also as badly afflicted? The presenter wondered if it could all be down to risky behaviour – but it seemed unlikely to me that one small, relatively sparsely populated part of the UK could be breaking the rules enough to explain those numbers.

Of course we all know now what was happening: a new virus variant, B.1.1.7, had arisen, after evolving mutations that increased its ability to transmit from one person to the next. Being much more contagious, it resisted the second lockdown and the Tier 3 restrictions that followed, rapidly replacing the previous circulating strain. Just a handful of mutations, some of them in the Spike gene, was all it took – fast-forward to just before Christmas, when the variant had begun to dominate in London, the rest of the Southeast and East England as well, and over forty other nations slammed their borders to UK travellers, causing chaos at ports and leaving hundreds of lorry drivers stranded for days. Now the new strain has been identified in other countries and is probably unstoppable, the only saving grace being that it seems neither to cause worse disease nor to render the current vaccines useless. Yet.

Decades before all of this, when I started thinking about the plot of my third novel, Cat Zero, I wanted to discuss virus evolution in an entertaining context that did not diminish the science needed to track and understand it. Of course I knew a lot about virus evolution from my PhD work on feline leukemia virus, which involved six years painstakingly identifying and characterizing point mutations, insertions and deletions accrued in Envelope (the virus outer protein analogous to the COVID Spike) during the course of infection in live safari cats. Less familiar with epidemiology, I had a few chats with my friend Bill Hanage, now a famous scientist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School, who advised me on some terminology and methods that I could adapt for my narrative. (This included using R0 as impenetrable jargon – which thanks to the pandemic is now, unhelpfully, a household term.)

When I was deciding on the epicentre for my fictional cat epidemic, I looked at a map of Southeast England and chose the most remote and unlikely place I could find: a small island called Sheppey, separated from the mainland by a wash of sea known as the Swale and connected by only one road bridge. It was a perfect place for a fictional epidemic to be initially “containable”. I pinpointed the first case, my “cat zero”, to a small bungalow on Seaside Drive in the town of Minster. When my protagonist, a troubled but talented scientist, took on the case following alarming reports from local veterinarians, she was soon hot on the trail of a series of mutations that seemed to be propelling the workaday feline virus into an increasingly worrisome direction.

Every time I look at a case map of England and see the dark purple stain spreading outward from Sheppey, I think about life imitating art. One day, after the story has reached its denouement and we re-surface into real life, we will look back on this strange chapter of history, a selective narrative fractured through the prism of a million different perspectives. What I will take away is the sheer heroism of all the scientists who raced against time to save us, even in the face of public misunderstanding and sometimes even abuse. My hope is that we will remember the lessons of this pandemic well enough to apply them swiftly and decisively against whatever plague comes next – and that instead of slashing research funding and pandemic readiness systems as before, we will increase the scientific resources and infrastructure necessary to craft a happier ending.

Well said Jenny!

Swale might seem remote, but is positively metropolitan by comparison with Shetland, which has also seen a surge in cases: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-55474128

In my view (and it’s just my view) the country should scrap the next school/university term and go into full lockdown until Easter at least. But nobody cares what I think.

Thanks Dom!

Interesting. I assume it is also B.1.1.7 getting into every crack and crevice of the UK now. You are probably right about the need for further lockdown – but I have no idea whether it will actually happen!

I’m amazed that the new variant appears to have originated on the very place you chose for the origin of Cat-Zero! A remarkable inadvertent prediction, and great writing. BTW, it’s made it to Seattle. Let’s all hope for a better 2021.