Despite my dedication to promoting the Lab Lit genre, I’ve always been an avid science fiction fan too. I admire how a good dystopian tale can transport you into a terrifying alternative future so convincingly that when you emerge from the spell, the relief of having escaped this fate (so far) can linger for days.

I felt a little bit like that after seeing the film “Don’t Look Up” (spoilers follow). It had its flaws, but the agonising run-up to the loss of our beautiful world – and then its terrifying execution – were so well portrayed that, weeks later, I’m still wandering around on my morning walks giving quiet thanks for the sky, the trees, the birds, and everything else we humans haven’t quite managed to ruin.

(As an aside, “Don’t Look Up” also had some nice lab lit qualities at the beginning. We see the world-weary astronomy PhD student clock into her telescope session, headphones on and utterly blasé – until she discovers the new comet. Then she claps her hands together and gasps with joy like a child. I think all scientists have been there.)

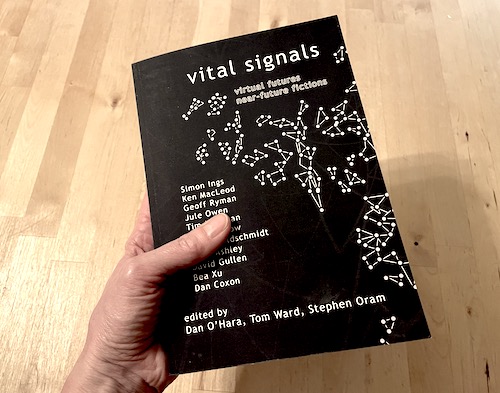

I’ve got a lot to learn about mastering the art of dystopian fiction, but I had the chance to practice when I was invited to take part in the anthology Vital Signals, from NewCon Press. Out on 25 February and available for preorder now, the collection offers visions of our potential future and draws attention to how science and technology might alter us as a species. There are lots of great authors in the collection and it’s been beautifully produced and edited.

I contributed to the “Disease” section of the anthology with a new story called “The Needs of The Few” (my early geeky childhood TV viewing showing through there). This short fiction imagines one possible extreme consequence of antibiotic stewardship, which is our current policy of not over-using the antibiotics that still work because we are running out of alternatives. The global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, predicted by Alexander Fleming back in the 1940s, is still a serious issue to this day and growing worse. The crisis was caused by flagrant abuse of these miracle drugs over many generations – taking antibiotics for non-bacterial illnesses, not finishing the full course of an antibiotic prescription, dosing livestock wholesale to prevent infection. Each inappropriate dose selects bacteria that are naturally resistant to the drug, and allows them to thrive and take over until inevitably, the drugs we have no longer work. Add to this the stalled pipeline of antibiotic discovery and the sheer difficulty of devising new ones, and you can see why stewardship is deemed necessary. This tenant means that all antibiotics, and especially any newly discovered ones, must be used sparingly and only when absolutely essential.

Stewardship is a very sensible policy in principle, and badly needed, but a rigorous, one-size-fits-all interpretation may deny people antibiotics who genuinely need them. I’m thinking in particular of people who suffer from chronic urinary tract infections that don’t register on the old-fashioned diagnostic tests, either because they are low-grade or because the tests themselves can be very insensitive. Many such people with genuine symptoms of infection are sent home from clinical consultations without a prescription, and continue to suffer, some so terribly that they cannot work, cannot leave their houses, cannot sustain a relationship – or, in some tragic extreme cases, cannot face living any longer. In this unfortunate situation, a disease with suboptimal diagnostics has collided with the idealogical force of a stewardship policy that is sometimes, in my view, too rigorously enforced.

But what, I wondered, would happen if the need for rigid stewardship suddenly became species-imperative? What if a deadly bacterial pandemic swept the world (I wrote this story before COVID19 came on the scene), and only one newly-discovered antibiotic could cure it? And what if you were a scientist who had dedicated her life to curing diseases, and had the means to break the law to help people with infections that weren’t “important enough” enough to risk treatment?

If you want to find out more, do pick up a copy.