Age is a slippery thing. Most days I still feel like that tentative new PhD student, pulling 80-hour weeks at the University of Washington Health Sciences Center in Seattle. By the red glow of the safelight, I’d feed dusky rectangles of film into the developing machine and they’d emerge clear, slightly sticky and covered with a primitive pattern of dark marks that would raise another dozen questions for every answer they revealed.

It was those messages from the void, more than the cupfuls of strong espresso, that kept me alert in the dead of night: the thrill of knowing somehow not as enticing as the ongoing chase, the truths just around the corner. One more experiment, one more gel, one more blot, one more session in the darkroom: endlessly onward. Messy biology would transform to meaning in front of my eyes: flasks full of dying cells becoming dots on a growth graph; viral genomes magicked into lurid pink bands on a Polaroid film; radioactive fragments of DNA transformed into international database entries of official sequence. All of this knowledge, amassed by my own hands, scrutinized by a brain still young and agile enough to remember PIN codes and passwords – to remember my own age, without having to count up from the year I was born.

And this period – so vivid, so strange, so compelling – was more than 25 years ago.

Where has that time gone? So much water has rushed past in between – a blur of existence punctuated by scenes of astonishing clarity. My viva lecture, a comfortable triumph with my parents (mother, still alive) smiling anxiously from the back row. Stepping off the Tube at Russell Square for my first postdoc with a suitcase full of key possessions, the rest a few months behind on a slow cargo ship bound for Felixstowe. Sitting on a sunny balcony in Amsterdam, waiting for my work permit to clear: wondering what on earth I’d done, leaving academia – and as I watched, a bird falling out of the sky, one moment flying, the next dead. On the dole, pacing the Amstel with its endless houseboats, terrified of a future that had no plan, no structure, no certain destination. My first day in publishing, going up the stairs in trepidation, behind quicker young people in their designer trainers and casual confidence. My return to the lab, like a moment out of my recurring dreams but this time, wonderfully real. And even this scene, nearly a decade in the past.

What’s it like, being old in the lab?

For starters, you no longer know all the lyrics to all the songs on the radio. Heck, you’ve never even heard of most of them – though you’re the only one in the lab who can mouth all three verses verbatim to Rupert Holmes’ Escape when the DJ decides to be ‘ironic’. (For any young non-scientists wondering what a ‘radio’ is, it’s a ancient, battered metal box that plays music – because nobody wants to set up their personal MP3 player or laptop and speakers in the same room as the concentrated hydrochloric acid.) You are deeply comfortable with any old piece of equipment (centrifuges with dials instead of touch screens; Mini-Protean 3 pour-your-own gel boxes), but a bit wary of new kit (such as the real-time PCR machine that costs more than your mortgage). Some of your on-the-fly math skills are a bit rusty, though you’ve kept your hand in by coaching generations of undergraduates who don’t seem to have been taught how to dilute solutions or calculate nanomolar solutions, and freeze like terrified rabbits when you ask them to.

But a few days ago, Dear Reader, I discovered the biggest handicap of all.

I can’t see a bloody thing.

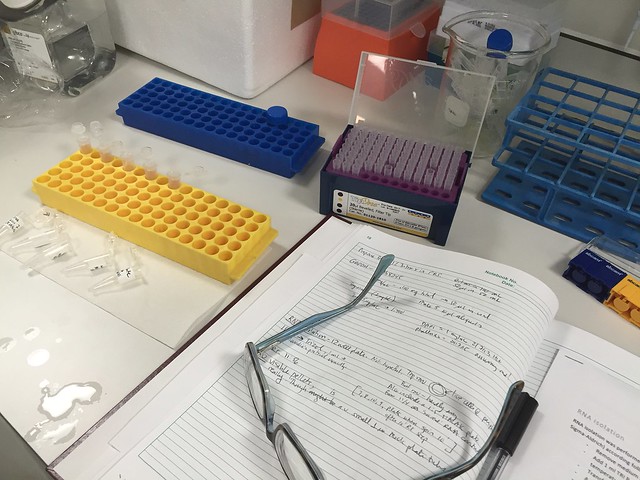

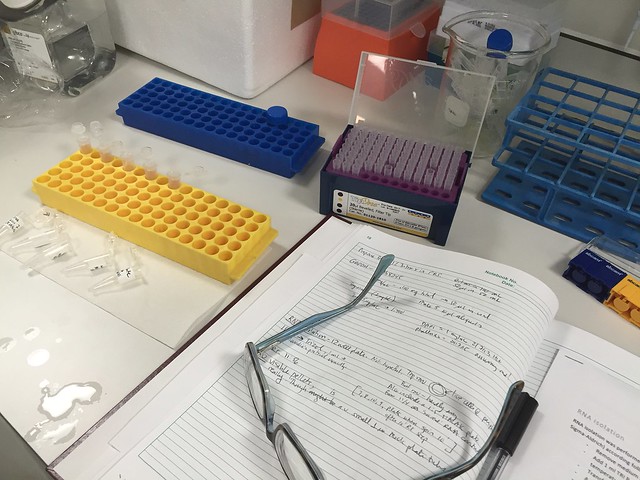

I mean, literally. I’ve just done my first RNA purification in about a decade, and I’ve got to the last step, where the precious substance – in theory – has been concentrated into a tiny, nearly transparent pellet at the bottom of my plastic tubes. I’m meant to be slowly decanting off the alcohol while being especially careful that the pellet doesn’t slide out and ruin the entire experiment.

And I can’t focus on anything closer than about three feet from my face – which is too far away to see a semi-invisible smear of transparent nucleic acid against the smoky translucence of the tube.

I can sense all the youngsters watching me in bafflement as, glasses removed, I hold the tube approximately one centimeter from my right eyeball, the smell of alcohol pungent in too-close nostrils, and then fumble around with the Gilson pipettor, thumping the barrel blindly onto the box and only managing to spear a tip on the third try.

Just then, a form materializes by my side. I put my specs back on and see one of my fellow PIs, a woman about my age. She looks with horror at the stuff strewn on my bench and says, “You’re not using TRIzol, are you? I haven’t used TRIzol in about 15 years. Why don’t you just use a Qiagen column?”

“I was trying to save money,” I say, sheepishly.

“You could have had the RNA in about half an hour, about ten times purer,” she informs me, quite unnecessarily. “Mind you, I remember when TRIzol first came out – it seemed like such a luxury at the time, not to have to prepare your own phenol.”

“I know, I know. Hey, do you remember having to treat everything with DEPC water to avoid degradation?”

“God, yes: wasn’t that a pain? And half the time it didn’t work anyway, because some stupid student would touch your stuff without gloves, and your Northern blot was just a big ugly smear of black.”

I now sense the youngsters hastily melting back into the undergrowth. For there is nothing more annoying than oldies reminiscing about the ‘bad old days’ of phenol extractions, phage cloning and isolating restriction enzymes from your own shit. Except they’re not even really sure what a restriction enzyme is, or phenol, or a Northern blot, nor how molecular biology actually works without a kit.

I don’t want to give you the impression that I’m against new tech – far from it. To wit, I was thrilled to discover that my PI friend’s lab housed not only a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, but one with eight channels. Check this beauty out:

I was even more thrilled to discover that, invisible or not, there actually was a sufficient amount of RNA in my tubes after all. These old hands? Apparently, they’ve still got it.

Victory dance time: “If you like piña colaaaaaadas…”