Last week I went to Germany to talk to a pharmaceutical company about my work on the blood protein, human serum albumin. It set me thinking. But first I need to tell you about albumin.

Albumin is a surprisingly abundant protein in the human body; you have about 200g of the stuff coursing through your veins and more still in the fluid that lubricates your organs. Though it normally works as a transporter for fatty acids and other greasy molecules that are poorly soluble in water, albumin can also absorb many types of drug molecule. This can be problematic: if drugs bind too tightly to albumin, they get trapped in the bloodstream and are less effective. If this happens with a promising new compound, drug companies have to try to modify it to reduce the affinity for the protein. But how do you know what changes to make?

My group, with funding from the BBSRC, MRC and the Wellcome Trust, has spent many years studying the structure of the protein and shown how fatty acids and different drug molecules stick to it. We have done this using X-ray crystallography — shooting X-rays at albumin crystals — to reveal the three-dimensional structure in fine detail; we get to see exactly how the atoms are arranged.

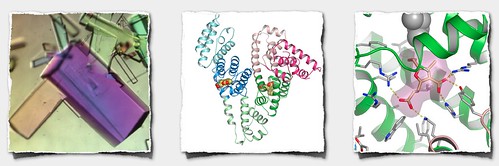

Crystals of albumin, the structure of the protein and a close-up of a drug binding site

Crystals of albumin, the structure of the protein and a close-up of a drug binding site

Though albumin has a (well-deserved) reputation for being difficult to work with, we have solved nearly 50 different structures of the protein bound to different molecules so we know quite a bit about what makes a molecule stick to it. Though I’m not very comfortable with the term, you could say that I’m a bit of an expert on the topic of drug binding to albumin. So from time to time I get asked by pharmaceutical companies to talk about our work.

I enjoy these industrial excursions. It amazes me that some people have so much confidence in the ability of science to generate products sold for profit that they will invest millions in the process. As an academic I still tend to see myself as something of an amateur, and industrial scientists as the professionals. I realise that’s a false distinction — one that does myself and my co-workers a disservice — but the industrial interest makes me feel I’m being taken seriously.

I know the pharmaceutical business is a flawed industry. I know about the dodgy marketing, the manipulation of clinical trials, the ghost author abuses, the fake journals. These things are unacceptable but, even so, there is a rigour, an exactitude to the business of making that seems to me as impressive as anything served up by pure research.

It is sometimes said or presumed that scientists look down their noses at engineers but I don’t know who these scientists are. I’ve not met any. For sure there are those who insist on the primacy of curiosity-driven research (no bad thing) or who bridle at the suggestion that they might have to contemplate the impact, economic or otherwise, of their work. But I suspect that even these ‘purists’ share my appreciation of the creative power of engineering — the conduit through which science changes the material world. For that reason I was pleased with last week’s news reports of a new £1m engineering prize.

I was also pleased to have the chance to see how our research on albumin is seeping into industry. There was strong interest in my talk in Germany and there were keen questions in the discussions that followed. For me these visits are sporadic. Other scientists will have more contact with industry but plenty of others will have less. I’m not sure how to foster increased contacts but I think this could be a good thing. It is likely to be important in bolstering knowledge transfer, which is one way to key into the economic value of science (a topic that has been treated with some interest by Jack Stilgoe and Colin Macilwain in the past day or two). I get the impression that there are big differences here between Germany and the UK.

At lunch my hosts and I compared education systems. I learned that it costs just a few hundred Euro each term to attend university in Germany and felt a pang of jealousy: next year UK students will be facing annual tuition fees of up to £9,000. The consequences for UK education have yet to be determined. Somehow, the Germans seem to have closed the virtuous circle — their education system supports a strong manufacturing base, which in turn earns enough to pay for an accessible education system. The German science budget is heading for a 10% boost, while in the UK science funding stagnates.

I know it’s a bit more complicated than that, and that better contacts with industry is only part of the solution. But how does the UK get to Germany from here?

My better half frequently advances the opinion that the Familie Elliott should take the personal route to ‘getting to Germany from here’ by re-locating there.

How you get the UK science base there is a rather more difficult question. Unless we’re all going.

So, how much room is there in your car?

Student fees in Germany are a fairly recent ‘innovation’ and are highly controversial. Although low in comparison to British fees I see them raising steeply over the next five to ten years. I hope I’m wrong but I fear that I’m not. The German universities are chronically underfunded and money from the state is certain to be reduced rather than increased.

Thanks for the comment. German students can be grateful at least that they are some way behind the curve on fees in comparison to their UK counterparts. But I suspect that’s cold comfort.

I wasn’t aware of the state of funding of German universities though I know that, on average, they don’t perform nearly as well as UK institutions in terms of research output. I gather they have recently ploughed funds into a few elite universities in an attempt to create a German ivy league but the rest seem to have to make do. I’m sure there are many other structural differences (less mobile career structure in unis?) but I have the impression that they do a better job of preparing students for high tech careers. In part I suspect that is because of a healthier attitude to engineering but I admit I don’t really know. What is apparent is that Germany has a healthier balance of trade.

“I know the pharmaceutical business is a flawed industry.”

I’m going to have to bite, here. Being about a third of the way through a four hour ethics course, because one of our clients–a big pharma company–insists that employees of its contractors complete the training, it has come home to me just how tightly regulated the pharma industry is.

That’s not to say there aren’t problems. But the companies and the regulatory bodies and governments are working to root out trouble and prevent unethical behaviour.

Academia, on the other hand…

OK, believe it or not I was trying to be balanced. I don’t mean to tarnish the entire industry, even though there are long-standing problems. After all, I have been quite prepared to work with most of the big names. Part of the reason why I am impressed by industrial set-ups is the motivation and professionalism of the people I have dealt with. For sure, there are many examples of very good practice.

And you are quite right to point out that the business of academia is also flawed – I never denied that even if I didn’t state it openly in this post.

Yeah, it just seems that it’s easy to rag on the pharmaceutical industry. Easy target, and I am very sensitive to it!

Somehow, the Germans seem to have closed the virtuous circle — their education system supports a strong manufacturing base, which in turn earns enough to pay for an accessible education system.

The key words here are manufacturing and base – for some reason, we Brits are great at inventing things but very bad at bringing them to the marketplace. I don’t know why this is, and I’m not sure anyone else does, either. I suspect it’s a combination of things such as chronic failure of public investment and high labour costs combined with a corporate attitude that’s hung-ho about starting companies, seeing them grow and flogging them (the British view) rather than staying with them for the long haul (the German model.)

Yes – it’s complicated. Your latter point overlaps with Will Hutton’s view (If I recall his book correctly — too many investors out for a fast buck.

But surely the cultural/structural differences aren’t insurmountable…?

I think that corporate attitude also goes along with a kind of enhanced sense of social responsibility in the people that both run and perhaps own German industry – who I suspect are still probably largely German – or at least, they are more German than the people that own British industries are still British. Anyway, from my talks with My Better Half I have the impression that fast buck-ery, and things like off-shoring all your production to the Far East so that you personally can be worth £ 1.5 Bn rather than £ 500 Million, are more widely disapproved of across German society than in the UK. So even other fairly wealthy people would see it as socially irresponsible and dishonourable (or at least vulgar) to do that kind of stuff – “Not what is proper’ and so forth.

Here in the UK all the other rich people would just be jealous.

I think this is also connected to the relative lack of meritocracy in the UK, where in the last 30 years wealth and privilege has become essentially hereditary again.

I think this is also connected to the relative lack of meritocracy in the UK, where in the last 30 years wealth and privilege has become essentially hereditary again.

Yes, it has long seemed to me that many company executives seem to treat their role as a sort of feudal title that allows them to enrich themselves with little thought of the merit or consequences. I see that even the Institute of Directors is now figuring out that this position is not tenable in the long run.

I guess that sense of living in a feudal state is one of the factors propelling the spread of the OWS movements…

Ben Goldacre has a nice term for these people, who seem especially prominent in the financial sector:

’till-dippers’

The Germans have this strange idea that industry should be run by experts; chemical plants are run by chemical engineers, car manufacturers by engineers etc. The British still think industrial firms should be run by somebody with a degree in classics from Oxbridge or a first class honours in history from Durham. Of course the Germans have no idea how to run a company 😉

That’s because all the chemical engineers trained in Britain go on to become merchant bankers.

Maybe the Germans and the British could get together and sort this thing out!

Apposite article by Aditta Chakraborty on the theme of the ‘politician-managed decline’ in British manufacturing in the Grauniad a couple of weeks back.