Since the beginning of the argument with Elsevier over their support of the Research Works Act (RWA) in the US and the announcement of the boycott of the publisher, I have been keen to stimulate dialogue. Elsevier seems to be interested in the same thing and their response to the research community, hesitant at first, is now being relayed by open letters from the organisation and comments (e.g. here, here and here) from various employees on blogposts and on Twitter.

This is good.

To continue the dialogue I’d like to pick up on a couple of points in the recent open letter from the publisher.

“Being criticized by even one researcher, let alone all the signatories of the petition, is difficult for a company whose reason for being is to serve the research community.”

This rather skips over the fact that Elsevier has a duty to make profits for its shareholders, which is another important reason for its being.

Then there is the question of their service to the research community. The publisher likes to see itself as working ‘for’ the researchers. They go on, in describing their activities:

“It’s work that is both complex and investment-intensive, performed by Elsevier employees working for a vast global community of more than 7,000 journal editors, 70,000 editorial board members, 300,000 reviewers and 600,000 authors. We are proud of the way we have been able to work in partnership with the research community to make real and sustainable contributions to science.”

That’s a touching reference to ‘partnership’ but it is important to be clear about the nature of that relationship. Most successful partnerships are either equal or agreed by mutual consent to be fair. Where does the balance of equality or fairness lie in our partnership with Elsevier?

There seem to be problems — witness the flare-up over the RWA. Even in a response that is supposed to address the concerns of their research partners, Elsevier cannot quite help making a slip of the pen:

“We have invested heavily in making our content more discoverable and more accessible to end-users and to enable the research community to develop innovative research applications.”

“Our content”? There they go again. How easily the publisher seems to forget where that content comes from. On Twitter Elsevier employee Liz Smith explained to me “‘Our’ content means the article we’ve invested in. It’s not our work and we know that.” I’d like to suggest that our partner tries harder to find a form of words that more clearly acknowledges the shared nature of the content. To be fair to them, however, perhaps the publisher is simply relying on the fact that most authors sign over to them the copyright of their journal articles.

The letter ends with an undertaking:

(to redouble) “our substantial efforts to make our contributions to that community better, more transparent, and more valuable to all our partners and friends in the research community.”

Partners and friends? There is truth in that. I am sure that many who work for Elsevier have come from scientific backgrounds (to focus on my own area) and are committed to the industry because they see it as a valuable contribution to the research enterprise. This was expressed to me by Liz Smith on Twitter, “I can honestly say we feel privileged to help get the awesome work scientists do out to as many people as possible.” I believe her.

But this is not the whole story. There seems to be a disconnect between many who work for the publisher and the ultimate aims of the business. The open letter is at least in part a PR exercise and so glosses over some of the more uncomfortable aspects of our friendship with the multi-billion dollar publisher.

Elsevier might like to think of itself as the friend of the research community but it doesn’t always treat it that way, as shown by the recently concluded negotiations on journal subscriptions with JISC Collections, the body that deals with publishers on behalf of UK Higher Education institutions. Having had to swallow above-inflation subscription prices rises for several years (in part driven by the demands of researchers who are largely ignorant of the cost implications), the UK HE sector now spends nearly £200m per year on access to journals and databases. That is about 10% of the QR budget paid to universities by HEFCE.

However, since the credit crunch, shrinking university budgets have obliged Research Libraries UK (RLUK), the organisation that speaks for the major research intensive universities and played a leading part in the negotiations, to take a firmer stand. Indeed they felt compelled late in 2010 to threaten the cancellation of the big deals (bundled subscriptions of numerous titles) with publishers like Elsevier and Wiley-Blackwell as part of their negotiating strategy.

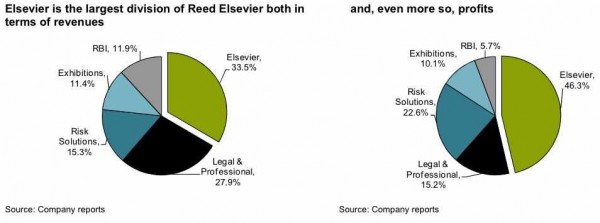

Perhaps such tactics should not seem surprising — they are part of the rough and tumble of commercial deal-making. But it’s not the sort of stance you expect to have to take with partners and friends. Especially when the customer ultimately seeking to negotiate prices is also the author who provides journal content for free, the editorial board member, also working without payment, and the peer-reviewer, again working at no charge to the publisher whose journals, in the case of Elsevier, are the most profitable arm of its business.

Reed Elsevier revenues and profits (2010). Elsevier is the STM publishing arm. Source: Bernstein Research (1)

Moreover, if Elsevier truly desires to encourage greater transparency with its partners in the academic community, they could start by releasing RLUK from the confidentiality clauses that they imposed on the deal that was reached at the end of last year. Debby Shorley, the head librarian at Imperial College who was active in the negotiation process, cannot tell me how much she pays for Elsevier journals. We therefore cannot have an informed conversation about decisions on journal subscriptions. That’s not helpful.

I’m afraid it is difficult at times to remember that many who work for the publisher are on the side of science.

But let’s continue to talk. Discussion, even if it is argument, is good. It brings things out into the open. Before all this business over the RWA and the Elsevier boycott I had not given sufficient attention to the interplay between the scientist and the publisher. I am now. And I’m not happy with what I see. I want better value for money and more open access.

Elsevier is correct to claim that it offers a range of open access options to authors but I think publishers are increasingly aware that the scientific community wants more. According to a briefing note I obtained from Bernstein Research (2), a publisher’s-only workshop was held in the spring of 2011 to address the questions, “Can we learn not just to live with open access, but to love it as well? Has the time come to turn the threat into an opportunity?”. That’s certainly a telling title and the invitation to that workshop outlined publisher thinking in more detail (with my emphases in bold):

“Open access is here to stay, and has the support of our key partners. Funders see it as the way to maximise access and impact for the research they fund, policy makers are under pressure to make it happen. Publishers know it is much more complicated and threatening to make it work than is apparent to the advocates and the fund holders. But we would benefit from having a compelling, coherent and above all positive story to tell about the role we can play in achieving these objectives“.

I say to my friends in the scientific community, let’s help our friends in the publishing industry to realise that opportunity.

(1) Reed Elsevier: The inevitable crunch point – downgrading to under perform because of growing concerns on Elsevier, Bernstein Research, 10 March 2011

(2) Reed Elsevier, Bringing down the house – Why Elsevier is vulnerable in its upcoming Big Deal negotiations, Bernstein Research, 29 March 2011

My thanks to Claudio Aspesi for making these documents available. A more recent briefing note that analyses the possible impact of the publicity surrounding the boycott is also an interesting read.

Update – 13-02-2012: Thanks to Debby Shorley for correcting me on the roles of the JISC collections and RLUK in dealing with publisher negotiations. Text amended accordingly.

It’s important to note that Elsevier’s “OA” is really sponsored access, as it does not, for many journals where the option exists, change any copyright arrangements.

Thanks for the clarification Benoit.

It’s actually impossible to determine what licence Elsevier’s “open access” articles are provided under — see What actually is Elsevier’s open-access licence?.

The closest thing I’ve got to an answer is this rather gnomic comment from Alicia Wise: “If memory serves I tweeted this info to you a few days ago. [If my memory serves, she did not — Mike.] Elsevier is experimenting with various licenses for our OA content. There are some bespoke licenses which permit non-commercial reuse, and some CC options including BY and NC-ND. This information also appears in different places on different articles/screens. We’re in a test-and-learn phase.”

Thanks Mike. I agree it would be good to have clarity on this from the publisher. I’d encourage them to comment here.

Perhaps it would be an idea for funders to lay down more explicit instructions as to what types of open access licences were to be followed by authors?

“Perhaps it would be an idea for funders to lay down more explicit instructions as to what types of open access licences were to be followed by authors?”

+1

Indeed, greater emphasis on BOAI-compliant Open Access licences e.g. CC-BY & CC0. So that amongst other dangers, we don’t unwittingly give text-mining rights control to commercial publishers to abuse for profit making purposes [4]

1. http://www.soros.org/openaccess/read

2. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

3. http://creativecommons.org/about/cc0

4. http://blogs.ch.cam.ac.uk/pmr/2012/02/10/elsevier-nature-and-content-mining-%E2%80%93-yet-another-digital-land-grab-%E2%80%93-wake-up-academia-and-fight-or-surrender-for-ever/

Thanks for the comment and links Ross.

“But we would benefit from having a compelling, coherent and above all positive story to tell about the role we can play in achieving these objectives“.

Too late. Automobiles don’t need farriers. Science is a “story” about the generation and dissemination of contributions to the “intellectual commons”. The publishing business is a “story” about profit facilitated by ownership and control of “intellectual property”. Chalk and cheese.

I suspect you may be right, phayes and there may be big changes afoot. However, some have been predicting big changes for the past decade and the scientific community has shown itself to be rather sluggish in embracing the opportunities posed by new publishing models (for some of the reasons outlined on drug monkey’s blog) .

A props nothing, your mention of farriers reminded me of one of my favourite poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins…

Since I got a name check in the post, and you kindly invited me via Twitter to expand on my comment on your blog, I’d like to offer a few thoughts on a couple of point in your post. I should say that although I work in the communications function (internal, employee comms) I’m not an official spokesperson for Elsevier. Like the vast majority of my colleagues I am just a passionate supporter of what we do

Every organisation, whether for profit or not for profit, needs to generate a surplus. Elsevier is a for-profit company, and we have to deliver value to our shareholders. But I would argue that shareholders, who provide us with our operating capital, would not be willing to continue investing in a business that did not also deliver value to authors, editors, reviewers, end-users, purchasers, etc.

A good part of that value comes directly from the research community, and I can see why researchers would object when we say ‘our content’. It’s a perhaps sloppy shorthand for the article that we have invested in: to get the work ‘in the system’, to help facilitate quicker peer review, to make it ready for reading in print and online, to make it discoverable, to make it immediately usable by your peers so that they can build on it; to maintain and upgrade the systems needed to do all of that. And the value we add doesn’t end with the content. We invest in the creation and marketing of new journals where there is a demand for them. We develop new technologies and platforms to access journal content and improve researcher productivity (e.g., ScienceDirect, Scopus, Scirus, CrossRef, Cross Check, Article of the future, text-mining tools, measurement tools). We invest in new processes and technology to help speed up the publication process so that your work can be accessed and cited earlier. And we take a financial risk on those things that governments and universities might not be able to take.

There is a strength that comes from our market discipline: we are scrutinised by investors, so we try to become ever more effective in what we do and to increase the value for money that we provide customers.

A word, too, on pricing. I have colleagues who are more knowledgeable than I on this topic. but I know them to be people of integrity, and they tell me this: print title prices no longer reflect either the effective price or real value of a journal in an electronic world. Electronic subscription agreements are the preferred option for most institutions, because of the value of the combination of content, form and function. Pricing in an e-environment is evolving, and we are listening to feedback and making changes gradually over time to ensure stability.

For the past decade, Elsevier’s average price increase for journals has been single digit, and within the lowest quartile of average price increases across all STM publishers. (Bear in mind that growth in the number of articles delivered has been running at 3-4% each year.) As the effective price paid per journal accessed has decreased, the number of journals accessed has increased, and the usage of those journals has grown by over 20% per year. Consequently, the average price paid per article downloaded has fallen by 80% since the late 1990s. And for those who argue that the price per article is artificially diluted by the inclusion of additional, bundled titles, we’ve found that 40% of usage is of journal titles that the library previously had not subscribed to.

It’s interesting that you quote the workshop invitation that said ” we would benefit from having a compelling, coherent and above all positive story to tell”. I think most publishers would agree that we need to do a better job of articulating what we do and why we do it. I personally appreciate the opportunity to have the conversation. I think by having it, we can indeed have friends in the research community.

Many thanks for taking the time to comment Liz. I’d like to try to address some of the points that you raise, most of which are about pricing and achieving value for money.

For sure Elsevier, like many other companies, is required to deliver value to its shareholders and will only to do so if it operates successfully within its chosen market. In part, companies achieve that by providing good products and services to their customers. But investor scrutiny is not a sufficient driver of value for money, since investors are primarily interested in the value they get from their investments.

Moreover, investor scrutiny won’t result in optimum value of money for customers if the market doesn’t operate effectively. And unfortunately the market in academic publishing doesn’t seem to work effectively in the interests of customers. In a paper published last year (warning: paywall), David Prosser, head of RLUK, described it as “dysfunctional’. The trouble is that, for example, a scientist looking for a paper in Cell cannot easily turn for an equivalent paper in Nature. Journals and their articles are ‘non-substitutable’ which gives publishers a kind of monopolistic power in the marketplace. That is accentuated, I would argue, when publishers grow to the size of Elsevier with thousands of titles in their hands. Prosser cites a European Commission study (PDF) into scientific publishing which concluded that:

The power of publishers (and relative weaknesses of institutional libraries — beholden to academics who did not care about the price of access) seems to account for the large price rises exacted in the past decade. You describe them as single digit but they were nevertheless running at twice the rate of inflation according to Prosser. Arguably, there is more content and more access but it’s far from clear that the savings realised from the move away from printing on paper have been passed on to customers. This is an area where more transparency would be helpful. With library budgets under a squeeze as never before, double-inflation increases were unsustainable and resulted in the hardening of the negotiating position in 2010-11.

Those budgetary pressures are not going to go away any time soon. With more scientists than ever before aware of the squeeze on funding (e.g. via Science if Vital) from the public purse and the consequent increase in incentives to justify our expenditure to the taxpayer, the demand for value for money (and open access, so the public can more easily see what they are getting for their investment) is only going to intensify.

Against that backdrop, it is little wonder that Elsevier’s support for the RWA has caused such an outcry. You rightly acknowledge, in referring to the value in published journals that “A good part of that value comes directly from the research community.” It would be interesting to try to quantify ‘a good part’. My guess is it’s well over 50% and this is another factor that makes the scientific publishing market different from standard models of ‘manufacturers makes widget; customer buys widget’ since there is large overlap between the manufacturer and the customer in scientific publishing.

My guess is that the scientific community is poised to scrutinise as never before the value that it gets from publishers.

“My guess is that the scientific community is poised to scrutinise as never before the value that it gets from publishers.”

I think you’re right! And we truly welcome it. We need to do a much better job of talking about the value we add.

I agree that shareholders are interested in their returns. But every business seeks return on investment, whether that investment comes from private capital, membership fees or other revenues. Being interested in your return on investment by definition requires being interested in the value the business is creating.

David Prosser of course will have his own reasons for describing the academic publishing market as “dysfunctional”, but I don’t disagree that it is a different animal. The fact is that funding, tenure, etc., are in part predicated on publication in high impact journals. We’re working hard to increase the quality of the journals we publish, because we want to attract the best authors and publish the best work. But as the boycott shows, there is still a choice. By the way, there may be an “ideal perfectively competitive private market” in theory, but is there one anywhere in practice?

Re pricing, we’re moving away from a ‘one size fits all’ approach, and most customers have a subscription agreement linked to their specific circumstances and content needs. A print percentage price increase doesn’t reflect the impact of price changes on these institutions. Our prices reflect the value of the content that we provide. That value is a combination of the quantity and usage of articles and the rate of inflation. In conjunction with customer-specific requirements – individual holdings, agreements etc. – this will translate into customised prices. Do we need to clarify our models? Yes, and I have colleagues who are working on that on a one-to-one basis with our customers.

We know that libraries are under financial pressure, and we are working with them to find solutions that work for them. We also know that library investment brings benefits to the institution. For example, in 2008, Elsevier worked with Dr Carol Tenopir and the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana to look at the ROI of academic libraries. This single case study demonstrated a $4.38 grant income for each $1.00 invested by the university in the library. Phase 2 looked at eight institutions from around the globe and found that six demonstrated a greater than 1:1 return in grant funding alone.

On the print cost savings, we’re basically talking about paper and postage; papers still have to be processed after submission and typeset. It’s not a huge savings compared to the massive ongoing investment that has to be made in keeping technology up to date and operational, and in finding better ways of making information discoverable. Incidentally, print hasn’t entirely disappeared; there will be some print costs so long as customers still want a print option.

Finally, I’m not sure how we would quantify “a good part”. I simply want to challenge the notion that publishers want to appropriate or take credit for the work of scientists. We don’t. The need for registration, validation and dissemination of research drives publishing, and we try to meet that need and make it easier and faster for authors to achieve those ends while also making it easier for others to find and build on your work. We are listening closely while the research community tells us what value for money means to them so we can keep doing that.

Thanks for the opportunity to respond.

Liz, many thanks for engaging in such detail. I am sure I’m not alone in saying that I truly appreciate it. There is a lot in your response that is worth of discussion, but to keep things reasonably brief I will focus on a single point.

You ask “By the way, there may be an “ideal perfectively competitive private market” in theory, but is there one anywhere in practice?” We all know that in reality no market is perfect. But that should not obscure the important distinction between markets which at least approach the free condition (e.g. car-repair services, where different garages compete on price and quality of service) and those which are not even close (such as Monsanto’s monopolistic control of the seed market).

A lot of people would see the current academic publishing very much towards the imperfect end of that spectrum for two reasons.

First — which at the moment Elsevier can’t do much about — each journal has a monopoly on its specific content. If I need a particular Cell paper, I have to get it from Elsevier. It doesn’t suffice to get an “equivalent” paper from a different journal in the way that I could for example have my car repaired by an equivalent garage.

Second — and here is where there is a real opportunity for change — there is currently a disconnect between the people who make the purchasing choices and those who have to pay. What I mean is, researchers choose which journals to submit to; and libraries have to cough up the subscriptions. We all know that when people are spending Other People’s Money, they are much less careful about how much is spent, and researchers will often (understandably) submit to a prestigious journal with a very high subscription price — to the detriment of their university’s library — rather than one that is cheaper. Because it doesn’t directly affect them financially.

This second disconnect is where Gold OA is a much better model than subscription: it reinstates the link between the person making the choice and the financial outlay. Researchers who want the cachet of publishing in an expensive journal have a real decision to make, rather than being able to shunt the costs off elsewhere. And this can only lead to a more efficient market.

And now we come to the point. An efficient market is good for consumers but ipso facto bad for vendors, who no longer get to exploit the inefficiency. No matter how much Elsevier, Springer and Wiley talk about wanting to partner with authors (and I am sure that most of the individuals who say these things sincerely mean them) the brutal truth is that if research institutions are able to reduce what they pay, then publishers will lose revenue — and I don’t see how corporate officers can be in favour of that. Isn’t there a fiduciary duty to increase shareholder value?

So with the best will in the world, I don’t see how it can be in Elsevier’s interests to fix the broken market that is scholarly publishing today. And sure enough, when I look beyond Elsevier’s public statements to its actual actions (the PRISM Alliance, support for the RWA, etc.), what I see is a company that is going out of its way to keep the market broken.

Do you disagree?

Let me answer first by telling you what I see within my company. I see individuals who, as you kindly concur, are genuinely committed to serving the scientific community. Whatever else might change, that won’t. Perhaps I’m an idealist, but I believe we can find a way forward that works.

What the future looks like, I don’t know. But in any industry, if the playing field changes, the players have to adapt. And I go back to my earlier comment that the value we add doesn’t end with content. I believe we can continue to find ways to be part of advancing science.

Liz – Let me echo Mike’s appreciation of your contribution to the conversation here. I think there’s still quite a gulf between our respective positions but at least I understand yours a bit better now (though I would like to know what lies behind the confidentially clause on the latest subscriptions deal and suspect Mike is still looking for clarification on the OA licences question raised at the top of this thread).

Your comment that “The fact is that funding, tenure, etc., are in part predicated on publication in high impact journals.” is true for now and one of the complicating factors in all this discussion. To my mind that is a problem of the scientific community’s own choosing (one also acknowledged by drug monkey). I know that Michael Eisen sees things very differently and am sympathetic to the need to break out of the glamour-mag mindset. This is one of the reasons why I favour the move to OA publishing models and moves to undermine the impact of impact factors. To that end I was interested to read the following in the Wellcome Trusts OA policy earlier today:

Now, if only we could get scientists to take that on board…

Just a note that this problem seems to be gradually fixing itself in at least some fields. For example, in the field of biology (I am a palaeobiologist), the 2010 JCR report listed PLoS Biology, an all-OA journal, in first place, with an IF of 12.916. Similarly, PLoS Medicine has a 2009 IF of 13.050, which compares pretty well with the BMJ’s 13.660.

Now I think that Impact Factor is a truly stupid number that measures all the wrong things, and is an appallingly poor proxy for article quality. Still and all: for those who do measure contributions by IF, Open Access journals are doing pretty darned well. Really unless someone is aiming for Science or Nature, saying “I can’t use an OA journal, I need to aim for higher impact” is pretty much nonsense now.

P.S. Yes, Liz, I am still looking for clarification on the OA licence used for Elsevier’s “sponsored articles”!

One of the areas of pricing where Elsevier and other publishers can be criticised is ‘double dipping’ – intentionally or unintentionally multiple charging for the same item. The risk is significant where a publisher is dealing with a large organisation. I’ve written about the risk of double dipping the NHS here – http://nelh.blogspot.com/2012/02/elsevier-double-dipping-and-nhs.html . If Elsevier are serious in their concern to avoid double dipping they could drop charges for converting papers to Open Access. Elsevier argue that paying a subscription and paying an OA fee are different – but both charges relate to the same cost – in effect the cost is being paid twice over.

I’m curious to know why your head librarian cannot tell you how much IC pays for Elsevier journals. Is it that she just doesn’t know – though presumably someone must – or is it that she is not at liberty to divulge the information. Since these costs come at least in part from Universities HEFC allocations, which is tax payers money, surely transparency demands that the sums are made public?

Whatever, £200M is a vast sum for UK Universities to spend on journal subscriptions, especially at a time when budgets are being frozen or cut. I wonder what would happen if HEFC, in conducting the next REF, were to actually reward investigators/institutions that chose to publish in free open access journals. What if a paper in Cell actually incurred a financial penalty?

She knows but can’t tell me because she is bound by the confidentiality clause (see last paragraph) that Elsevier has insisted on (if I have understood correctly). I gather that no other publisher imposes such a clause. It doesn’t make for transparency in the ‘partnership’.

Your suggestion about using the REF as a driver mechanism is an interesting one. In principle, it may already be happening since reviewers are being asked to consider citations rather than impact factors and there is evidence that OA publications are more highly cited (I’m sure I’ve seen the link somewhere but the length of this day is getting the better of me…). However, in practice, I can’t believe that the reviewers will be able to properly discount impact factors — one more reason for trying to tear ourselves away from their tyranny.

Replying here as nesting is out of room above. I have colleagues who are far more knowledgeable about such things, so my answer may not enlighten.

Confidentiality clauses are not uncommon. I’d be interested if your librarian is able to tell you what she paid for, e.g., Nature. I suspect you’ll say that it being common doesn’t make it right; I’m just pointing out that it’s not an Elsevier-only construct. I think it’s important to say again that we negotiate with each customer individually. The price one library pays has no bearing on what another one might pay, for the reasons I outlined in one of my earlier comments. Therefore comparing one against another wouldn’t tell you much and looking at the price without taking into account the many factors leading to it wouldn’t tell you much either. A number in a vaccuum isn’t helpful.

I honestly don’t know about our OA licenses. My understanding from Alicia Wise is that we are trying different approaches. But I will try to find out more.

I gather that, in fact, confidentiality clauses are relatively uncommon. You’re right that Elsevier and Nature (NPG) impose them but most other publishers that we deal with (e.g. Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, CUP, OUP, American Chem Soc., RSC, IOP) do not. If these agreements prevent me from knowing how much my institution pays for subscriptions, that loss of information is one of the things that leads to market inefficiency. I don’t need to compare with other institutions but I have an interest in knowing that the university is getting value for money from the deals that it makes. The publisher presumably demands confidentiality as being in their interest — I don’t see how it is in mine. This brings us back to the question of Elsevier’s declared intention of being more transparent with its partners. I very much appreciate your candour here, Liz, but as you say, you are not an official spokesperson for the organisation. So I’d be interested to know how far along the road to transparency the higher ups are prepared to travel.

I honestly don’t know about our OA licenses. My understanding from Alicia Wise is that we are trying different approaches. But I will try to find out more.

Thanks for pursuing this. I’ve found Alicia surprisingly difficult to get hold of — the only response I have managed so far is this comment (on another article on Occam’s Typewriter) which says basically the same thing you just said.

But, you know, it really won’t do at all. Elsevier’s Sponsored Articles page invites authors to pay a specific amount of money ($3000) but doesn’t say what specific benefits you get in exchange for that. It’s as though you said you’d sell me chocolate for $10, but couldn’t tell me how much chocolate or what brand or flavour, and when I asked for clarification you replied “we’re experimenting with various quantites and flavours for our chocolate”.

(Apologies if you feel I am shooting the messenger!)

I actually really appreciate the feedback. I will try to elucidate at some point.