The UK government’s new policy to reduce bureaucracy in research institutions aims at an easy target. But the bonfire of administration lit by the Prime Minister’s chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, risks burning down the foundations of much-needed efforts to value the many different people on which the health of UK R&D depends

Should an interest in bureaucracy be a protected characteristic? I think a case can be made. But Dominic Cummings thinks not and that is why his fingerprints are all over the government’s recent policy paper announcing its determination to reduce bureaucracy in research, innovation and higher education.

A direct result of this policy is that universities applying for funding to the National Institute of Health Research no longer need to hold a silver Athena SWAN award affirming their commitment to gender equality. But the policy reaches even further. Universities are entreated not to feel under pressure to participate in any other voluntary schemes that increase bureaucracy and distract unis from their ‘core activities’. The schemes are not named but will include the Race Equality Charter (REC), Stonewall’s Workplace Equality Index (which aims to support LGBTQ+ people) and the government’s own Disability Confident campaign. The message seems clear: efforts to promote equality, to value diversity, or to be inclusive are not core. They are a bureaucratic distraction and are no longer welcome.

Except that the message isn’t at all clear, a feature we have come to expect from the Johnson administration of which Cummings is such a central part. This is a surprise given Cummings’ evident prowess as a campaigner. But he has played his own prominent role – as Mr Magoo – in the confused drama of Britain’s attempts to deal with Covid-19.

Of course, Cummings isn’t against all bureaucracy – just the bad bits that get in the way of delivering desirable outcomes. In an extremely long blogpost from 2014 he recounts story after story of how dysfunctionality within the civil service frustrated his and Michael Gove’s attempts to drive through a policy on Free Schools at the Department of Education in the early years of the Cameron-Clegg coalition of 2010-2015. Cummings is a disruptor, who wants to move fast and break things; his focus is on outcomes. To get things done he wants the power to issue orders that will simply be obeyed, and to fire those who fail to deliver. He looks longingly at the executive agility enjoyed by small start-up companies and super-rich entrepreneurs like Larry Page, Peter Thiel and Elon Musk.

And he has a point. There is a tendency for large organisations to fixate on process rather than outcome, and it takes visionary leadership to overcome that. But for all its extraordinary length and numerous hyperlinks, his analysis lacks sophistication or any evident concern for people. His faith in the capacity of the decentralised processes of markets and science to solve problems has some merit, but ultimately comes across as blinkered. The market failures that led to the banking crisis of 2007 and the imbalance of power between nations and mega-corporations like Google, Facebook and Amazon are not discussed. Cummings’ scientific preoccupations are centred on physics and mathematics rather than on biology and sociology, where the diffuse complexity of the systems under study would soon snuff out the over-confidence of his pronouncements.

Tellingly, there is no mention in the piece of attempts to sell his vision for educational reform, which may have been a worthy one, or to win the hearts and minds of civil servants to the cause. Instead there is a litany of complaints about them having the temerity to want to spend time with their families, either by working flexibly or taking a holiday now and then. You get the sense of a man for whom the ends justify the means, and his means come across as pretty mean.

Cummings is right to express frustration at the civil service’s tendency to deal with incompetence by promoting the offender out of department where they have wreaked havoc. Healthy organisations demand that actions have consequences. But his argument has been torpedoed by his own refusal to acknowledge fault for breaking lockdown rules last Spring, an episode that eroded so much public trust in the government’s efforts to deal with the public health crisis. His unrepentance is all of a piece with Cummings’ messianic arrogance: rules are for less important people. He has little conception of how respect of the law can bind organisations and nations in common purpose.

The bigger picture is absent too from his attempts to staff his office. There is a nod in his blogpost to the value of cognitive diversity, but this extends only far enough to include the different professional experiences of his white, male colleagues. Cummings’ recent recruitment of ‘weirdos and misfits’ has been notable only for its success in attracting young men who have flirted with racism and eugenics.

For all his wide reading, Cummings would do well to consult the works of Margaret Heffernan, who writes with far greater insight and human understanding on how to get the best out of people in large organisations.

Which takes me back to the large organisations known as universities. No one who works in one will be unaware of the frustrating bureaucracy that grows out of their complex structures and the multitudinous demands placed upon them – by students, staff, funding agencies, regulators, and government. Increasingly, those demands have rightly included the need to show how our universities are advancing across the battlegrounds of equality, diversity and inclusion.

The goal of refashioning traditionally hierarchical institutions so that they are open to all people of talent is a noble, necessary and extraordinarily difficult one, as the slow pace of change attests. To reach it requires not just vision and leadership, but excavation of every procedural nook and cranny.

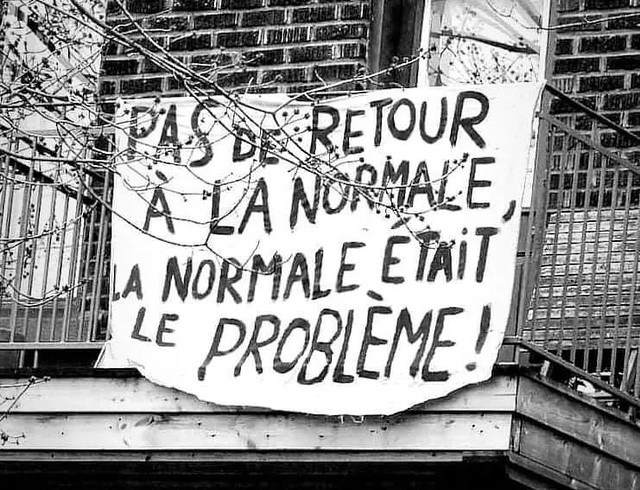

In many institutions, like my own, progress towards the goal is benchmarked and incentivised by the array of voluntary frameworks mentioned above: Athena SWAN, the REC, the Stonewall WEI and the Disability Confident scheme. Each requires a long, deep dive into data and processes. Applications for Athena SWAN and REC award are particularly onerous in this regard and have rightly come in for criticism. They are seen as overly bureaucratic tick-box exercises that can distract energy and attention away from the ultimate goals. Cummings is right to remind us to keep our eyes on the prize. The outcome that matters is real change, not the badge earned from a successful application.

My female colleagues in our medical research departments are well aware of the shortcomings of Athena SWAN. Nevertheless, they are seriously disappointed by the loss of the leverage that the link between Athena SWAN and NIHR funding brought to the university’s efforts to advance gender equality.

The drive to reduce bureaucracy would have been better framed as a drive to reduce unnecessary bureaucracy. Unfortunately, government has given the impression it believes that attention to the culture with universities should be downgraded in favour of a focus on our ‘core’ activities, which it defines as research and education. The insistence on the primacy of these core activities is repeated no fewer than four times in the government’s policy paper. In my view that is a fundamental error. The environment within which academics and support staff operate is critical to the quality of the research and education that they deliver.

It is to be hoped that university leaders will maintain support for EDI work, but in times when financial pressures are only increasing, some institutions may be tempted to drop the subscriptions needed to remain part of charter schemes. The NIHR’s commitment to equality and diversity may have dimmed, but other major UK funders such as the Wellcome Trust and UKRI have signalled their intent to move these issues to the centre of their decision-making on funding. In one of her first public statements as UKRI’s new chief executive, Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser has declared her intention “to create a system that values difference”.

Science Minister Amanda Solloway has also sent some encouraging signals. In a speech made just days after the policy paper appeared, she spoke passionately about the importance of diversity and well-being for the future of UK R&D. It would be helpful if she could clarify how her vision is to be enacted alongside the Cummings’ arson attack on bureaucracy.

Ironically, the government’s policy may actually undermine attempts by Advance HE to reduce the bureaucratic burden of Athena SWAN and the REC and to make them more effective tools for change. Advance HE’s dependence on subscriptions might tempt them to leniency in judging weak applications for fear that universities, now told they should “not feel pressured to take part” in such schemes, will then withdraw to pursue equality by their own lights.

Naturally, it is healthy always to review how we might do things better (as has happened, albeit stutteringly*, with Athena SWAN and as is now happening with the REC). Alternative and more effective ways of advancing equality, diversity and inclusion in our universities could certainly be envisaged. But it would be foolish to assume these will not involve bureaucracy or administration. Easy solutions are not available for hard problems. If you want to bring about organisational and cultural change, you cannot avoid the grunt work of rethinking every process, every training programme, every decision, every appointment. Cummings may have a point about bureaucratic bloat, but the values under-pinning his prescriptions are invisible. Beyond vague notions of devolving power – and his supremely unhelpful lessons in rule-breaking – he has little to offer in the way of workable alternatives. That bit is up to us.

*See also this analysis from my OT co-blogger, Athene Donald.