Viburnum x bodnantense, a winter-flowering shrub

I’m happy, and I don’t know why.

Usually I dread this time of year, the period between demobbing the Christmas tree and the daffodil-studded benevolence of mid-March. It stretches on endlessly, the dreary coldness, the frosts interspersed with rain that pools on pavements and hardly ever coalesces into snow, and above all the afternoon darkness, which on overcast days might as well be twilight.

Last year, my diary reminds me that I was resorting to ordering from flower catalogues to take the edge off – huddled in a chair with candles lit on a mid-winter evening, daydreaming about dahlias whose future blooms felt almost mythical. During this period, probably in late January, I was walking Joshua to school when I registered a deep, hyacinth-like spring scent. Looking up, I discovered a shrub I had never noticed before, spilling over the garden fence of one of the grand Georgian listed houses, its woody branches lush with pink bunches.

What seasonal misfiring could have coaxed such delicate flowers out into a world encased in a hard frost? This singular oddness made it easy to identify online: Viburnum x bodnantense, which blooms from November until March on purpose, not as an accidental aberration of climate change. (Apparently bees and other pollinators can over-winter in gardens, at least in this climate.) Of course I had to order one for my own garden in the hopes that it might cheer me up during midwinters to come, but that just added something more to the long list of things I was waiting for.

Well, that ‘mental health viburnum’ has been flowering for weeks out back this year, but for some reason, I don’t need it. I have been happy, more or less non-stop, since I hoovered up the brittle fir needles from the carpet on New Year’s Day.

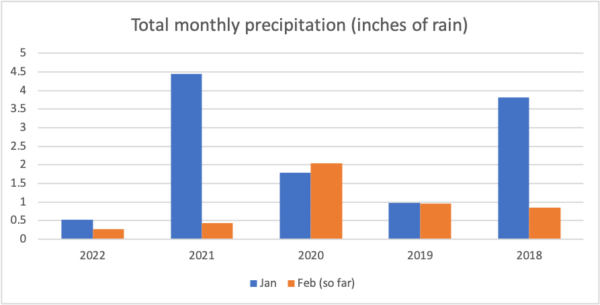

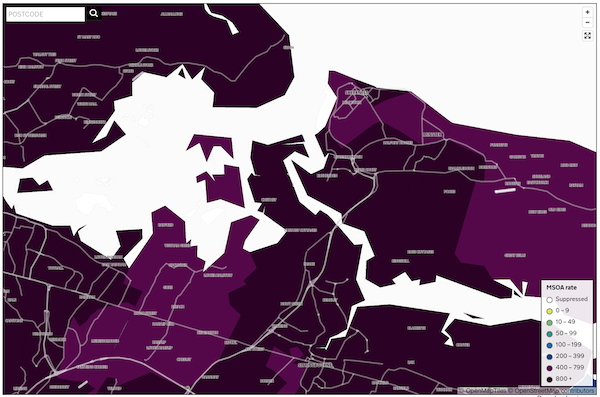

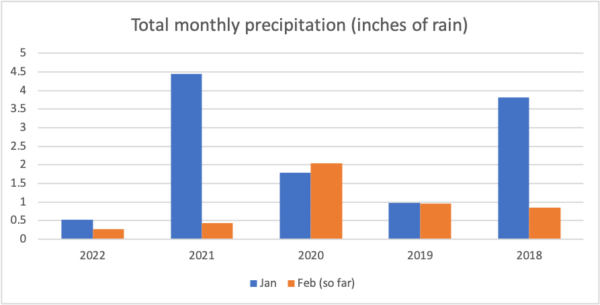

It’s so out-of-character to have dodged the winter blues that I’ve been trying to work out why. The weather is probably part of it – it’s been remarkably fair these past few months. I had a dig around the Met Office pages but couldn’t easily find the sunshine data I wanted. Fortunately Richard’s weather station, its shiny cups spinning tidily on the summerhouse roof like some steampunk NASA apparatus, could at least tell me about the rainfall. Sure enough, this January and February have been drier than any year since he started collecting data in 2018. It’s been so dry, in fact, that I’ve stopped checking the forecast before heading off to London, and have yet to be caught without an umbrella. What little rain we’ve had has tended to be overnight.

But this is just quantitative data, dead numbers on a chart. They cannot conjure up the astonishing beauty of the mornings we’ve had. From the bedroom window, the dawn sky glows a million different shades, each morning subtly different from the last. Venus is tangled in the great sycamore tree lurking over the nearby park, as bright as an incoming aircraft against peachy or coral or golden streaks of cloud. To the left, there are a few minutes each day when the ships on the Thames far below glow like molten lava, until their moment in the sun is gone and they reclaim their drab grey.

Faraway ships on the Thames, set fire by sunrise

Atop Windmill Hill where I walk after dropping the boy at school, the sky changes further, so unique and lovely that my phone has filled up with portraits of the same horse chestnut trees over and over: the silhouettes never change, but each image is infinitesimally different in the colour and texture of its backdrop. I do my normal brisk circuit, puffing at the crest of the climb, crunching frost under my feet, sucking icy air into my lungs, greeting the same dog walkers, taking in the same maritime views of the flat silver ribbon of estuary below, yet it never once feels tired or overly familiar. I understand now that this formerly dreaded period is not a rigid stasis, but a subtly developing season-scape that you only notice if you are amidst it every day. Green shoots push up from the muddy earth, tree buds start to swell, the tenor of the songbirds eases and lifts, dog cherries bloom in the otherwise barren hedgerows.

The same trees, from different angles and days, January and February 2022

And there is light – acres and acres of light, so bright that it dazzles and spangles, colluding with the frigid air to make a tiny joyful headache deep behind the eyes.

I consider my pre-pandemic routine at this time of year. I would leave the house just after 6 AM, in darkness, work all day in a lab and office with no windows, slip out of the hospital around 5 or 6 PM into darkness again. The only time I could ever see the sun was on the weekends – when it was more often than not raining. Last year I didn’t have these routines, because of lockdown, but hadn’t started my morning walk routine, and in January, it was raining almost constantly. So maybe that is the simple answer: I’ve been starved of light.

Now Spring is nearly here: our garden blooms with hellebore, snowdrops, and the first crocuses and daffodils. It’s good to see them, but they slipped in without me realising they weren’t there. Because somehow, I’m not waiting for anything anymore.

Joshua presents his first crocus of the year