In a kinder, happier age, when I used to write regularly for the Guardian’s science blog network, I would post summaries of the books I had read at the end of each year. Since the network closed in 2018 I have rather lost the habit. Looking back a the list of titles I got though in 2019, I realise how much I share with Robin Ince the problem of retention. I can only marvel at those who seem to be able to analyse the plotlines and arguments of books that they have read months and years ago. My recollections are more impressionistic. I should take more notes.

But let me at least share with you my impressions, such as they are. Here, in the order that they were read, is my year’s worth of books.

- A Bigger Prize: why no one wins unless everyone wins, Margaret Heffernan

- The Hunt for Vulcan, Tom Levenson

- Science 3.0, Frank Miedema

- The Good Immigrant, Various

- Heroic Failure: Brexit and the politics of pain, Fintan O’Toole

- I’m a joke and so are you, Robin Ince

- Utopia for Realists, and how we can get there, Rutger Bregman

- The Tyranny of Metrics, Jerry Muller

- Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez

- Superior: the return of race science, Angela Saini

- The New Silk Roads: the present and future of the world. Peter Frankopan

- Made to Stick, Chad and Dan Heath

- Natives: race and class in the ruins of empire, Akala

- Intelligence, Stuart Ritchie

- The Lagoon, Armand Marie Leroi

- The Gene Machine, Venki Ramakrishnan

- Beyond Weird, Philip Ball

- Adventures in the Screen Trade, William Goldman

- Red Notice, Bill Browder

- Manhattan Transfer, John Dos Passos

- The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt

- Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

- Generous Thinking: A radical approach to saving the university, Kathleen Fitzpatrick

- Translations, Brian Friel

It has been another bad year for reading fiction – just two novels and one play. Co-incidentally, both novels were largely set in New York, separated by about a century. While I disliked the fragmented, panopticon storytelling in Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer, Tartt drew me page by page into her intricate web of love and loss. The movie version of The Goldfinch was a bland disappointment, but Fabritius’s original painting, which I finally saw in the Mauritshaus in The Hague in October, radiated complex, new life.

It’s also not been a great year for reading books by women – just five-and-a-half* out of twenty-four. That said, it’s arguably also been a good year since three of my top four picks of 2019 were by women: Angela Saini’s Superior, a magnificent and powerful exposition of the science of race and the racism of science; Caroline Criado Perez’s brilliantly illuminating Invisible Women – which does that rare thing of making you see the world anew; and Margaret Heffernan’s A Bigger Prize, a lucid and disarming examination of the dark side of competition.

The fourth spot goes to The Lagoon, by my Imperial College colleague Armand Leroi, whose affectionate and deeply informed guide to Aristotle’s science I found wonderfully companionable. (I reviewed Superior for the Cosmic Shambles blog back in July and would agree with every word of Adam Rutherford’s assessment of The Lagoon. I’m afraid I only managed to tweet about Heffernan’s and Criado Perez’s books).

Beyond that, I enjoyed to a greater or lesser extent every book I read. Levenson’s The Hunt for Vulcan was a nicely wrought tale of how science actually works, while O’Toole’s Heroic Failure helped me a little more to deal with the pain of Brexit. In Natives Akala provided a personal and political examination of racism in the UK; along with The Good Immigrant it was a chance to listen to voices that are still too often unheard.

Peter Frankopan’s The New Silk Roads returned in the 21st Century to the ground he had covered historically and magisterially in The Silk Roads (which I read in 2017), while Philip Ball’s Beyond Weird did not disappoint; if it still left me somewhat baffled, that is only because I raced through it on my summer holiday. When relaxing I should really stick to easier reads. On that same holiday I enjoyed William Goldman’s gossipy Adventures in the Screen Trade, a behind-the-scenes look at the movie business and was electrified by Bill Browder’ terrifying story of corruption and murder in Putin’s Russia (Red Notice).

This past week I have finished off Kathleen Patrick’s Generous Thinking, which touches on the over-metricisation of academic life, a theme also covered in Muller’s The Tyranny of Metrics and Bregman’s Utopia for Realists. I have found inspirational material in all three books for my roles championing equality, diversity and inclusion at my university and as chair of DORA, an organisation campaigning to reform research evaluation. All three authors are searching for ways to repair the damage done to ideas of the ‘public good’ by the relentless machinations of the market**. I will surely draw on their wisdom in the year to come.

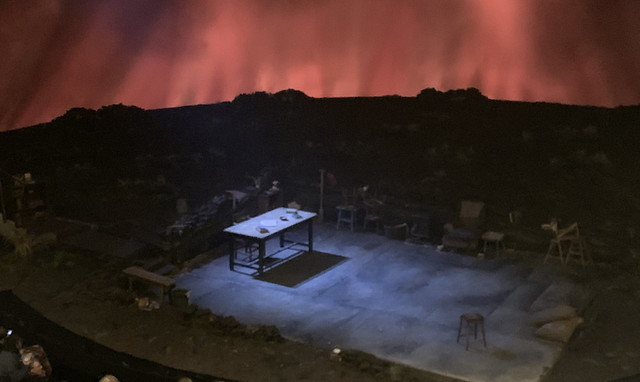

And finally, I went back to Brian Friel’s Translations, a play I first saw in Boston in the mid-1990s and then again a couple of weeks ago at the National Theatre in London. Although I felt that the drama was ill served by the staging in the most recent production, I was sufficiently stirred to revisit a text that is a richly layered meditation on language, history, memory, and belonging.

None of the above does proper justice to the books or their authors but I hope it might light a few flickers of interest for some people. I have already embarked upon my first title for 2020, Oliver Morton’s The Moon: a history of the future, which even in the first chapter is proving to be poetically entrancing.