I’d ban all automobiles from the central part of the city. You see, the automobile was just a passing fad. It’s got to go. It’s got to go a long way from here.

~Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Both at work and on teh interwebz, people are full of tales and advice about how to be green and reduce one’s carbon footprint. Although I cannot recall asking for advice on becoming less of an environmental insult, I receive it fairly frequently, usually in the form of “you oughtta.” “You oughtta become a vegan”, or “You oughtta stop using air conditioning, even when it’s eleventy hundred degrees in the shade”, or “You oughtta hand-wash and air-dry your gross anatomy scrubs”, or “You oughtta grow everything you eat.” The only suggestion that does not make me roll my eyes and think get realz, is “You oughtta ride your bike to work.” This last dictate is within the realm of possibility, at least when there’s not major construction along the shortest route to work, and in fact the construction, when completed, might make cycling along the route safer. At the moment, there are 8-inch dropoffs into trenches filled with rebar, metal mesh, and broken concrete.

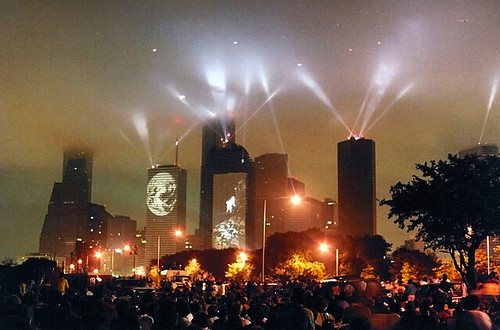

I live just over six miles from the medical center where I work, and typically leave home early enough that I don’t have to spend much time stuck in traffic. With the current construction, though, I often have to take a slightly longer (eight miles) route to and/or from work, and as most of it is along a very busy state highway, it’s not suitable for cycling. But I do feel vaguely guilty about my commute, even though I drive a fuel-efficient Honda, and try to complete shopping errands on the route home. The internal combustion engine is undeniably bad for air quality, something I know anecdotally from dissecting the lungs of former urban dwellers, in gross anatomy lab. Many of the students, expecting perfect pink lungs in the thorax of a non-smoker, are surprised by the dark inclusions scattered across most cadaveric lungs. “I think this person was a smoker!” … no, smokers’ lungs look like something you’d empty out of the charcoal pan of your backyard grill (unless you’re a raw foods vegan and never grill anything, of course).

Air pollution, Victoria Harbor, Hong Kong

Photo by Yym1997, under GNU Free Documentation License

The US Environmental Protection Agency regulates particulate matter (PM) defined as “inhalable”, i.e. coarse particles between 2.5 and 10 micrometers in diameter, and fine PM, less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, both of which can penetrate into the lungs. Most fine particle pollution in the US consists of secondary particles, which form through atmospheric reactions of sulfur dioxides, nitrogen oxides, and other compounds emitted by industries, power plants, and motor vehicles. Particulate matter is one of six pollutants for which there are National Ambient Air Quality Standards, under the Clean Air Act in the US. The EPA lists a number of health effects from exposure to inhalable particle pollution, including airway irritation, decreased lung function, aggravated asthma, and nonfatal heart attacks. Chronic exposure to particulate matter can be assessed by measuring the carbon load of airway macrophages, collected in sputum samples; this carbon load is correlated with the proximity of a person’s residence to busy, major roads. Using this approach, Jacobs and colleagues (2011) showed that in nonsmokers with diabetes, higher levels of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), a biomarker for atherosclerosis and arterial plaque formation, were associated with increased carbon load in airway macrophages. Particulate matter from traffic affects the health not only of the lungs, but the of cardiovascular system as well.

Air pollution, Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

Photo by ILJR, under GNU Free Documentation License

If one is concerned about exposure to inhalable particle pollution, what is the best way to commute to work (given that telecommuting, e.g in a wearable office such as cromercrox’s, is ideal, but not possible for everyone)? Two recent studies in the Netherlands address this modern eco-quandary. In Arnhem, a medium sized Dutch city, Zuurbier and colleagues (2010) measured exposures to inhalable coarse and fine particles and to soot in diesel- and gasoline-fueled cars, in diesel and electric trolley buses, and along two bicycle routes with low and high traffic intensities. Inhaled doses of air pollutants were estimated, based on the heart rates and ventilations per minute of healthy volunteers in each of the transport modes. Not surprisingly, inhaled pollution doses were highest for cyclists along high-intensity traffic routes, but these researchers argue that the positive health effects of cycling outweigh the negative effects of inhaled pollution.

A different approach, using life table calculations to determine mortality impacts in life-years gained or lost, when transitioning from car to bicycle for daily trips, yielded the same basic conclusion. In a 2010 paper, de Hartog and colleagues focused their quantitative comparisons of driving vs. cycling on air pollution exposures, road traffic injuries, and physical activity. Of course, estimated inhaled air pollution doses and risks of a fatal traffic accident are higher for cyclists than for drivers. On the other hand, the health benefits of physical activity, including decreased cardiovascular disease and mortality, are substantial for cyclists. The researchers calculated a gain of 3 to 14 months from the increased physical activity, which outweighs the potential mortality effects from inhaled pollution (0.8 to 40 days) and increased traffic accidents (5-9 days). Switching from driving to cycling has societal benefits too, with decreased air pollution in urban areas, and might lead to changes in urban planning, such as inclusion of more bicycle routes and lanes. Athene recently described her ability to commute by bicycle in Cambridge; with developments of greenway trails and bicycle lanes in my own city, I hope to be able to commute to work safely by bicycle in the near future.

References:

de Hartog JJ, Boogaard H, Nijland H, Hoek G (2010) Do the health benefits of cycling outweigh the risks? Environ Health Perspect 118, 1109-1116. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901747

Jacobs L, Emmerechts J, Hoylaerts MF, Mathieu C, Hoet PH, Nemery B, Nawrot TS (2011) Traffic air pollution and oxidized LDL. PLoS One 6(1):e16200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.011.6200

Zuurbier M, Hoek G, Oldenwening M, Lenters V, Meliefste K, van den Hazel P, Brunekreef B (2010) Commuters’ exposure to particulate matter air pollution is affected by mode of transport, fuel type, and route. Environ Health Perspect 118, 783-789. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901622