Cixin Liu: The Dark Forest This is the sequel to The Three-Body Problem, which I read last month. In that book, astrophysicist Ye Wenjie sends a signal into space that alerts another species to human existence. The species inhabits a planet that orbits chaotically in a system of three suns. As a result, this planet, Trisolaris, is subject to extreme and unpredictable climate swings. When the Trisolarans learn of Earth’s equable situation, they launch an invasion fleet. In the centuries that the Trisolaran fleet will take to reach Earth, humans do their best to think of ways to counter the Trisolaran menace. It turns out that the Trisolarans have a way to infiltrate all human communication in real time. But they have a weakness, for, unlike humans, they are completely incapable of deceit. Human thought, in human brains, remains opaque to them. Thus the humans come up with the Wallfacer Project, in which four humans are chosen to think deep thoughts and possibly come up with a scheme to counter what comes to be seen as an otherwise insuperable threat. The least likely of the four Wallfacers is unambitious astronomer Luo Ji. Nobody knows why Luo has been chosen — except that someone, somewhere, keeps trying to kill him. This leads Luo into what at first seems an unlikely partnership with rough-hewn detective Shi Qiang (my favourite character from the first book). This book is as rich and as deep and as full of marvels as The Three-Body Problem — and as full of absorbing red herrings, diversions and dramatic plot twists. To sum up, it’s a cross between the fable of the Three Little Pigs and an exegesis on the Dark Forest Hypothesis — that the reason why the Universe seems devoid of intelligent life is that the civilisations that last are those that do their best to remain hidden. For in the Dark Forest, there are wolves. Like The Three-Body Problem, The Dark Forest is a tour de force of modern science fiction. Moving on to Death’s End, the final book in the trilogy…

Cixin Liu: The Dark Forest This is the sequel to The Three-Body Problem, which I read last month. In that book, astrophysicist Ye Wenjie sends a signal into space that alerts another species to human existence. The species inhabits a planet that orbits chaotically in a system of three suns. As a result, this planet, Trisolaris, is subject to extreme and unpredictable climate swings. When the Trisolarans learn of Earth’s equable situation, they launch an invasion fleet. In the centuries that the Trisolaran fleet will take to reach Earth, humans do their best to think of ways to counter the Trisolaran menace. It turns out that the Trisolarans have a way to infiltrate all human communication in real time. But they have a weakness, for, unlike humans, they are completely incapable of deceit. Human thought, in human brains, remains opaque to them. Thus the humans come up with the Wallfacer Project, in which four humans are chosen to think deep thoughts and possibly come up with a scheme to counter what comes to be seen as an otherwise insuperable threat. The least likely of the four Wallfacers is unambitious astronomer Luo Ji. Nobody knows why Luo has been chosen — except that someone, somewhere, keeps trying to kill him. This leads Luo into what at first seems an unlikely partnership with rough-hewn detective Shi Qiang (my favourite character from the first book). This book is as rich and as deep and as full of marvels as The Three-Body Problem — and as full of absorbing red herrings, diversions and dramatic plot twists. To sum up, it’s a cross between the fable of the Three Little Pigs and an exegesis on the Dark Forest Hypothesis — that the reason why the Universe seems devoid of intelligent life is that the civilisations that last are those that do their best to remain hidden. For in the Dark Forest, there are wolves. Like The Three-Body Problem, The Dark Forest is a tour de force of modern science fiction. Moving on to Death’s End, the final book in the trilogy…

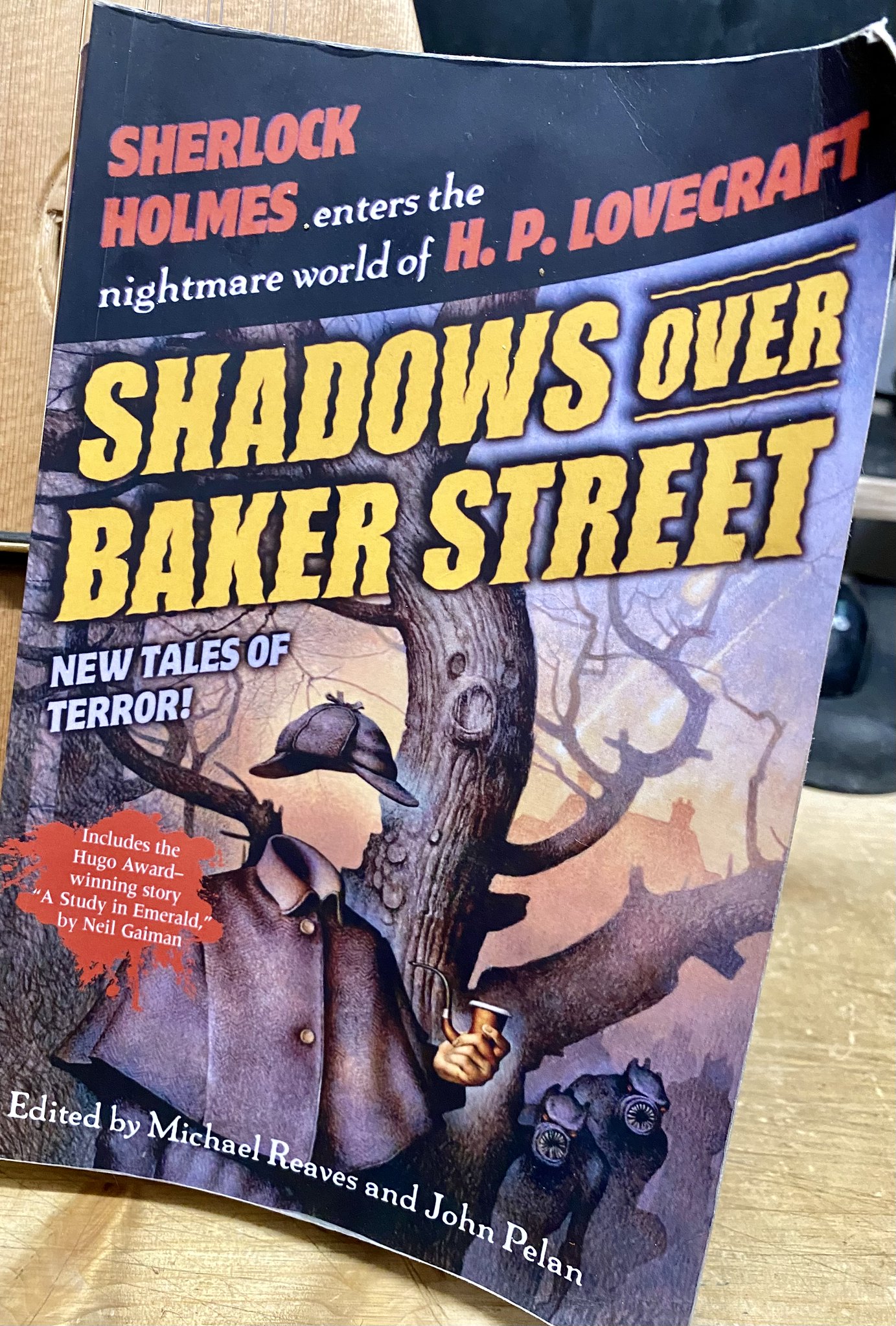

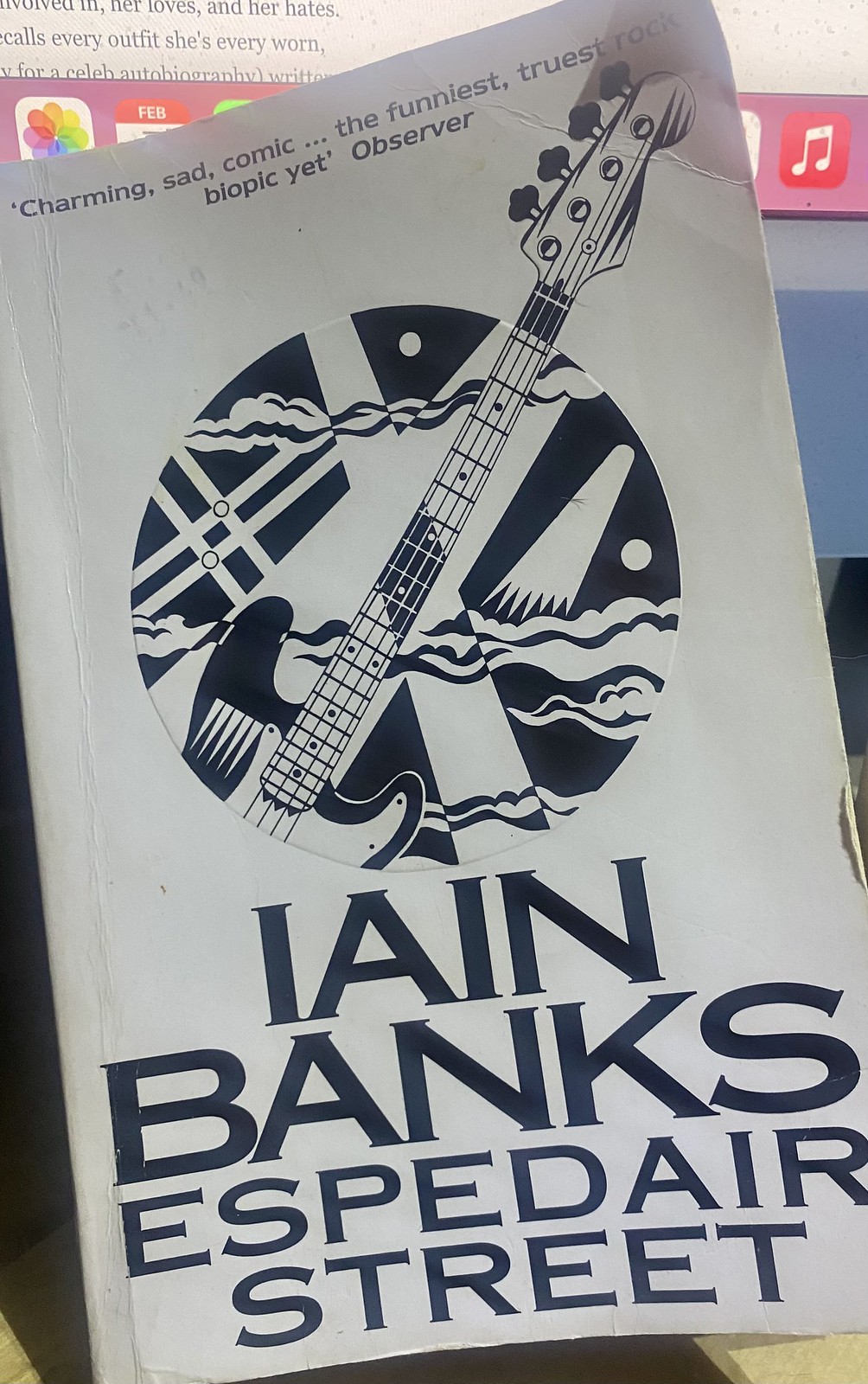

Cixin Liu: Death’s End This novel begins in an unlikely place and time — Constantinople, as it is about to fall to the Turks in 1453. A prostitute discovers that she has amazing magical powers… which fail just when they are most necessary. The significance of this is revealed later. Back to the near future, the United Nations, keen to raise funds, start a cheesy scheme to ‘sell’ star systems to the public. Few take up the offer, but one is terminally ill Yun Tianming, a former college classmate of brilliant astrophysicist Cheng Xin, who secretly has a crush on her. Having come into money just before his death, Yun Tianming buys Cheng Xin a distant star system. The significance of that is revealed later, too. Later still, Yun … or rather, his brain … is sent by Cheng Xin in an experimental probe to spy on the advancing Trisolaran fleet, but is lost. Meanwhile, the now aged Wallfacer Luo Ji (from The Dark Forest) comes up with an ingenious deterrent that will prevent the Trisolaran fleet from attacking the Earth — a threatened broadcast into space of the location of Trisolaris, which will bring down a so-called ‘Dark Forest Strike’ from an unknown alien assailant. He moves from being Wallfacer to Swordholder, wielder of the deterrent. But this action runs the risk of exposing the Earth, too, at some future date. The Trisolarans call the Earth’s bluff just as Luo Ji hands the sword to his successor, Cheng Xin — who fluffs it. The significance of that, too, becomes apparent later. The Trisolarans invade the Solar System, but the deterrent is sent anyway by Gravity, one of the few spaceships that managed to evade the invading Trisolarans. Trisolaris is destroyed, and Earth seeks to find ways to either send a message of goodwill (thus preventing a strike) or to discover ways to protect the Solar System. Centuries later they are aided by an unlikely ally — Yun Tianming, who had been picked up by the Trisolarans and reconstituted into fully human form. He drops hints about possible strategies to Cheng Xin in the form of a fairy story, something that his Trisolaran handlers will not understand. Sadly, the humans — as it turns out — completely fail to understand the message, with dire consequences. But that is only the half of it, and what I have written hardly begins to convey the beauty, grandeur and melancholy of this stupendous book. Just like The Three-Body Problem and The Dark Forest, Death’s End is full of old-fashioned SF super-science wound into engaging personal stories that called to mind everything from the aliens in Carl Sagan’s terrific novel Contact (read the book: please avoid the film adaptation, so dreadful that even Jodie Foster could not save it) to Flatland, a fantasy on life in two dimensions. For it turns out that space is not the wilderness we always thought it was. What we humans think of as the unshakeable laws of physics, such as the number of spatial dimensions, and the value of the speed of light in a vacuum, have been repeatedly adulterated by hyper-technical civilisations that are constantly at war, and the Universe we know is the bombed-out wreck of what was once an Edenic state. Like its predecessors in this majestic trilogy, Death’s End combines prose as delicate and beautiful as a traditional Chinese brush painting with huge passages of exposition that shouldn’t really work, but rather than hold up the narrative, they only increase the tension. I found it by turns suspenseful, exciting and at times intensely moving. I can safely say that The Three-Body Problem, considered as a trilogy (for it is just one long story), is the first book I have come across that knocks The Night Circus off its perch as the best book I’ve read in the past decade, and that Cixin Liu is the most compelling author of hard SF I’ve come across since I first read the nouveau space opera of Iain M. Banks and Alastair Reynolds. Having devoured the trilogy as audiobooks, I shall now buy the dead tree versions which I’ll set up at home where they’ll take pride of place in my alphabetically arranged SF library between Le Guin (Ursula) and Lovecraft (H. P.). Having said that, I might put The Three-Body Problem on a separate shelf, all on its own, as a shrine, and worship at it. For The Three-Body Problem trilogy is a masterpiece in anyone’s cosmos.

Cixin Liu: Death’s End This novel begins in an unlikely place and time — Constantinople, as it is about to fall to the Turks in 1453. A prostitute discovers that she has amazing magical powers… which fail just when they are most necessary. The significance of this is revealed later. Back to the near future, the United Nations, keen to raise funds, start a cheesy scheme to ‘sell’ star systems to the public. Few take up the offer, but one is terminally ill Yun Tianming, a former college classmate of brilliant astrophysicist Cheng Xin, who secretly has a crush on her. Having come into money just before his death, Yun Tianming buys Cheng Xin a distant star system. The significance of that is revealed later, too. Later still, Yun … or rather, his brain … is sent by Cheng Xin in an experimental probe to spy on the advancing Trisolaran fleet, but is lost. Meanwhile, the now aged Wallfacer Luo Ji (from The Dark Forest) comes up with an ingenious deterrent that will prevent the Trisolaran fleet from attacking the Earth — a threatened broadcast into space of the location of Trisolaris, which will bring down a so-called ‘Dark Forest Strike’ from an unknown alien assailant. He moves from being Wallfacer to Swordholder, wielder of the deterrent. But this action runs the risk of exposing the Earth, too, at some future date. The Trisolarans call the Earth’s bluff just as Luo Ji hands the sword to his successor, Cheng Xin — who fluffs it. The significance of that, too, becomes apparent later. The Trisolarans invade the Solar System, but the deterrent is sent anyway by Gravity, one of the few spaceships that managed to evade the invading Trisolarans. Trisolaris is destroyed, and Earth seeks to find ways to either send a message of goodwill (thus preventing a strike) or to discover ways to protect the Solar System. Centuries later they are aided by an unlikely ally — Yun Tianming, who had been picked up by the Trisolarans and reconstituted into fully human form. He drops hints about possible strategies to Cheng Xin in the form of a fairy story, something that his Trisolaran handlers will not understand. Sadly, the humans — as it turns out — completely fail to understand the message, with dire consequences. But that is only the half of it, and what I have written hardly begins to convey the beauty, grandeur and melancholy of this stupendous book. Just like The Three-Body Problem and The Dark Forest, Death’s End is full of old-fashioned SF super-science wound into engaging personal stories that called to mind everything from the aliens in Carl Sagan’s terrific novel Contact (read the book: please avoid the film adaptation, so dreadful that even Jodie Foster could not save it) to Flatland, a fantasy on life in two dimensions. For it turns out that space is not the wilderness we always thought it was. What we humans think of as the unshakeable laws of physics, such as the number of spatial dimensions, and the value of the speed of light in a vacuum, have been repeatedly adulterated by hyper-technical civilisations that are constantly at war, and the Universe we know is the bombed-out wreck of what was once an Edenic state. Like its predecessors in this majestic trilogy, Death’s End combines prose as delicate and beautiful as a traditional Chinese brush painting with huge passages of exposition that shouldn’t really work, but rather than hold up the narrative, they only increase the tension. I found it by turns suspenseful, exciting and at times intensely moving. I can safely say that The Three-Body Problem, considered as a trilogy (for it is just one long story), is the first book I have come across that knocks The Night Circus off its perch as the best book I’ve read in the past decade, and that Cixin Liu is the most compelling author of hard SF I’ve come across since I first read the nouveau space opera of Iain M. Banks and Alastair Reynolds. Having devoured the trilogy as audiobooks, I shall now buy the dead tree versions which I’ll set up at home where they’ll take pride of place in my alphabetically arranged SF library between Le Guin (Ursula) and Lovecraft (H. P.). Having said that, I might put The Three-Body Problem on a separate shelf, all on its own, as a shrine, and worship at it. For The Three-Body Problem trilogy is a masterpiece in anyone’s cosmos.

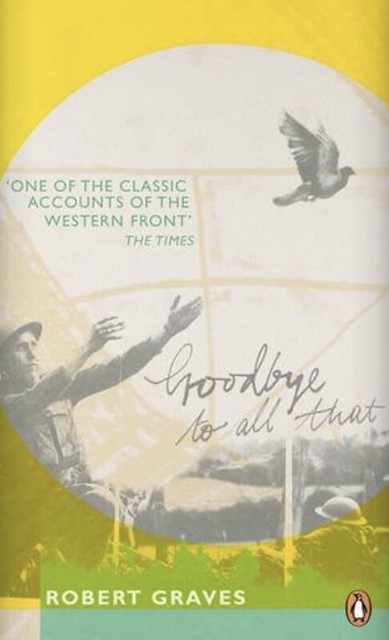

Donald L. Miller: Masters of the Air As you both know, Offspring#2 is the Gee family’s resident projectionist, with a knack of discovering televisual emissions that others might enjoy. So it was that she spotted Masters of the Air, a mini-series about the lives, loves, horrible deaths, incarcerations and occasional survival of the boys (they were, really, just boys) of the American bomber crews stationed in East Anglia during the Second World War. And so Offspring#2 passed me the book of the film, as it were, which turns out not to be a drama at all but a serious and well-researched work of military history, a genre I rarely touch, if ever. Well before Allied infantry set foot in Hitler’s Fortress Europe, and while the sea lanes were still prowled by U-boats, the crews of the US Army Eighth Air Force (the US Air Force did not become a service separate from the Army until 1947) flew their B-24 Liberators and B-17 Flying Fortresses over Germany, at first unescorted by fighter support, with the aim of the pinpoint destruction of Germany’s industrial infrastructure (the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt feature strongly) and do so in broad daylight, with rather small bombs. They largely failed, and that they were mercilessly shot up by the Luftwaffe is to be expected, but US planners felt that such a stiletto approach would be more humane than the bludgeon wielded by the RAF, devised by the head of Bomber Command, Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, of saturation bombing of German cities by night, with much larger bombs. The strategy only began to achieve success after D-Day, when fighters that could escort the bombers became available, and when strategists finally realised that striking Germany’s oil refineries and synthetic oil plants would cripple the Reich. That, and Hitler’s hurried scheme of devoting resources into futuristic weapons such as ballistic missiles and jet aircraft that would be payback for the destruction of German cities, but which came too late. In the end, though, the inaccurate targeting of the Eighth Air Force ended up converging with the merciless slaughter dealt by RAF Bomber Command. Masters of the Air is an intriguing if rather dense read, and shows, once again, that the schemes of military theorists far from the front are tested by many others with their lives, and underlining that old dictum that the best-laid plans of any military strategist rarely survive first contact with the enemy.

Donald L. Miller: Masters of the Air As you both know, Offspring#2 is the Gee family’s resident projectionist, with a knack of discovering televisual emissions that others might enjoy. So it was that she spotted Masters of the Air, a mini-series about the lives, loves, horrible deaths, incarcerations and occasional survival of the boys (they were, really, just boys) of the American bomber crews stationed in East Anglia during the Second World War. And so Offspring#2 passed me the book of the film, as it were, which turns out not to be a drama at all but a serious and well-researched work of military history, a genre I rarely touch, if ever. Well before Allied infantry set foot in Hitler’s Fortress Europe, and while the sea lanes were still prowled by U-boats, the crews of the US Army Eighth Air Force (the US Air Force did not become a service separate from the Army until 1947) flew their B-24 Liberators and B-17 Flying Fortresses over Germany, at first unescorted by fighter support, with the aim of the pinpoint destruction of Germany’s industrial infrastructure (the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt feature strongly) and do so in broad daylight, with rather small bombs. They largely failed, and that they were mercilessly shot up by the Luftwaffe is to be expected, but US planners felt that such a stiletto approach would be more humane than the bludgeon wielded by the RAF, devised by the head of Bomber Command, Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, of saturation bombing of German cities by night, with much larger bombs. The strategy only began to achieve success after D-Day, when fighters that could escort the bombers became available, and when strategists finally realised that striking Germany’s oil refineries and synthetic oil plants would cripple the Reich. That, and Hitler’s hurried scheme of devoting resources into futuristic weapons such as ballistic missiles and jet aircraft that would be payback for the destruction of German cities, but which came too late. In the end, though, the inaccurate targeting of the Eighth Air Force ended up converging with the merciless slaughter dealt by RAF Bomber Command. Masters of the Air is an intriguing if rather dense read, and shows, once again, that the schemes of military theorists far from the front are tested by many others with their lives, and underlining that old dictum that the best-laid plans of any military strategist rarely survive first contact with the enemy.

Amor Towles: A Gentleman In Moscow Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, late of ‘Idle Hour’, an estate near Nizhny Novgorod, returns to Russia from Paris after the Revolution to set his grandmother’s affairs in order. He is rounded up by the Bolsheviks, who, rather than shoot him for being a ‘social parasite’, have what seems to be a worse fate in store. He is made a ‘former person’ and confined for life to the luxurious Hotel Metropol, just opposite the Bolshoi Ballet and within sight of the Kremlin, there to live at the state’s expense, in a tiny attic room, as he is forced to watch the collapse of his privileged world. But the Bolsheviks hadn’t reckoned on the resourcefulness of their prisoner. Rostov’s late guardian, the Grand Duke, had instilled in the young Count not only perfect manners, but an unshakeable maxim: you must become the master of your circumstances, lest you become mastered by them. So Rostov adapts to his new life and finds in it contentment as he encounters poets, actors, waifs, strays, journalists, diplomats, party apparatchiks, petty bureaucrats, movers and shakers among the hotel’s guests. His old-world decorum finds him taking a job as Head Waiter at the hotel’s prestigious Boyarski restaurant, as well as advising the New Russians on how best to conduct themselves in foreign company. This perfectly constructed novel is every bit as elegant and well-comported as its protagonist, with wry, funny asides and delicate prose lightly concealing the ups, downs — and horrors — of the Soviet Union from its birth until the early 1950s. I found it most affecting. Now I’ve finished, I find myself missing Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, known to his friends as Sacha, a man with a steely resolve buried, seeming very deeply, beneath his well-groomed exterior.

Amor Towles: A Gentleman In Moscow Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, late of ‘Idle Hour’, an estate near Nizhny Novgorod, returns to Russia from Paris after the Revolution to set his grandmother’s affairs in order. He is rounded up by the Bolsheviks, who, rather than shoot him for being a ‘social parasite’, have what seems to be a worse fate in store. He is made a ‘former person’ and confined for life to the luxurious Hotel Metropol, just opposite the Bolshoi Ballet and within sight of the Kremlin, there to live at the state’s expense, in a tiny attic room, as he is forced to watch the collapse of his privileged world. But the Bolsheviks hadn’t reckoned on the resourcefulness of their prisoner. Rostov’s late guardian, the Grand Duke, had instilled in the young Count not only perfect manners, but an unshakeable maxim: you must become the master of your circumstances, lest you become mastered by them. So Rostov adapts to his new life and finds in it contentment as he encounters poets, actors, waifs, strays, journalists, diplomats, party apparatchiks, petty bureaucrats, movers and shakers among the hotel’s guests. His old-world decorum finds him taking a job as Head Waiter at the hotel’s prestigious Boyarski restaurant, as well as advising the New Russians on how best to conduct themselves in foreign company. This perfectly constructed novel is every bit as elegant and well-comported as its protagonist, with wry, funny asides and delicate prose lightly concealing the ups, downs — and horrors — of the Soviet Union from its birth until the early 1950s. I found it most affecting. Now I’ve finished, I find myself missing Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, known to his friends as Sacha, a man with a steely resolve buried, seeming very deeply, beneath his well-groomed exterior.

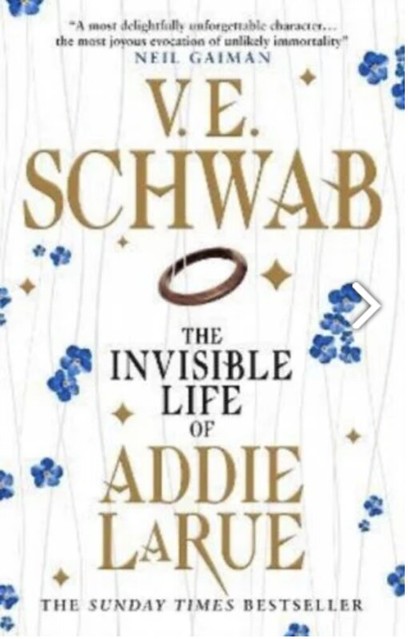

Susanna Clarke: Piranesi A young man called Piranesi lives in a strange, Borgesian world, an infinite series of gigantic marble halls styled on classical lines, and ornamented by uncountable statues. The highest halls are full of cloud: the lowest, inundated by the sea. Piranesi is content, making fires of dried seaweed, eating delicious concoctions of seaweed, mussels and fish, communing with the many birds that flock the halls, and tending to the needs of the various mummified corpses found, now and again, in odd corners unoccupied by statues. The only other living person is ‘The Other’, with whom Piranesi meets each Tuesday and Friday. But all is not as it seems. There are intrusions from another world, revealed at first by odd facts, such that the bones of one of the dead people are stored in a box marked ‘Huntley and Palmer’s Family Circle’; and the mention, by The Other, of nonsensical words such as ‘Battersea’. The unravelling of Piranesi’s world is seen through his eyes — or, rather, through his meticulous diary entries, for Piranesi documents the events as obsessively and seemingly as uncomprehendingly as the autistic boy in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time. At first one is inclined to think that Piranesi is a psychiatric patient, and all indications suggest that this is the case. But as with everything in this story, nothing is really what it seems. Not even Piranesi. A beautiful book, if slightly unsettling.

Susanna Clarke: Piranesi A young man called Piranesi lives in a strange, Borgesian world, an infinite series of gigantic marble halls styled on classical lines, and ornamented by uncountable statues. The highest halls are full of cloud: the lowest, inundated by the sea. Piranesi is content, making fires of dried seaweed, eating delicious concoctions of seaweed, mussels and fish, communing with the many birds that flock the halls, and tending to the needs of the various mummified corpses found, now and again, in odd corners unoccupied by statues. The only other living person is ‘The Other’, with whom Piranesi meets each Tuesday and Friday. But all is not as it seems. There are intrusions from another world, revealed at first by odd facts, such that the bones of one of the dead people are stored in a box marked ‘Huntley and Palmer’s Family Circle’; and the mention, by The Other, of nonsensical words such as ‘Battersea’. The unravelling of Piranesi’s world is seen through his eyes — or, rather, through his meticulous diary entries, for Piranesi documents the events as obsessively and seemingly as uncomprehendingly as the autistic boy in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time. At first one is inclined to think that Piranesi is a psychiatric patient, and all indications suggest that this is the case. But as with everything in this story, nothing is really what it seems. Not even Piranesi. A beautiful book, if slightly unsettling.

Ferris Jabr: Becoming Earth Those who seek for life elsewhere in the Universe first need to understand this: that life does not just exist on Earth. It is everywhere. Life clothes every surface. Everything that is living hosts other living things on, inside and around it, and these motes host smaller things too. Life modifies the Earth to make its habitat amenable to yet more life. Even the inanimate world might be very different were it not for the all-pervading influence of life. In this evocative hymn to life, journalist Ferris Jabr shows just how much life has shaped the Earth during its long history. Life enhances, speeds up, facilitates geology. Everyone knows that we owe our breathable atmosphere to life, our nourishing soil. Fewer will realise that without life, plate tectonics might not be what it is. Most of the minerals extracted from the Earth would not exist without life. In his quest to understand the interconnections between Earth and life, Jabr climbs dizzying towers into the canopy of the Amazon rainforest to show how forests create their own weather, and descends deep into old mine workings to show how life thrives far underground. And yes, he meets a centenarian James Lovelock, originator of the ‘Gaia’ theory of how living things regulate the environment to keep it equable. Jabr is no blind follower of Gaia, though. To him, the whole planet is not a living thing — instead, Earth has come to be shaped by life in ways that could never have happened had life never existed. Loving and lyrical, in some ways this reminded me of classic nature writing such as Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. While Jabr reminds us of the current threats to the climate from human activity, he notes that progress is already being made. Things might not be as bad as they seem. For we humans are just as much a part of nature as the worms that burrow kilometres underground in search of bacteria, or the aeroplankton of spores and living dust that the winds carry in the air far above. [DISCLAIMER: this book was sent to me by the publisher for an endorsement].

Ferris Jabr: Becoming Earth Those who seek for life elsewhere in the Universe first need to understand this: that life does not just exist on Earth. It is everywhere. Life clothes every surface. Everything that is living hosts other living things on, inside and around it, and these motes host smaller things too. Life modifies the Earth to make its habitat amenable to yet more life. Even the inanimate world might be very different were it not for the all-pervading influence of life. In this evocative hymn to life, journalist Ferris Jabr shows just how much life has shaped the Earth during its long history. Life enhances, speeds up, facilitates geology. Everyone knows that we owe our breathable atmosphere to life, our nourishing soil. Fewer will realise that without life, plate tectonics might not be what it is. Most of the minerals extracted from the Earth would not exist without life. In his quest to understand the interconnections between Earth and life, Jabr climbs dizzying towers into the canopy of the Amazon rainforest to show how forests create their own weather, and descends deep into old mine workings to show how life thrives far underground. And yes, he meets a centenarian James Lovelock, originator of the ‘Gaia’ theory of how living things regulate the environment to keep it equable. Jabr is no blind follower of Gaia, though. To him, the whole planet is not a living thing — instead, Earth has come to be shaped by life in ways that could never have happened had life never existed. Loving and lyrical, in some ways this reminded me of classic nature writing such as Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. While Jabr reminds us of the current threats to the climate from human activity, he notes that progress is already being made. Things might not be as bad as they seem. For we humans are just as much a part of nature as the worms that burrow kilometres underground in search of bacteria, or the aeroplankton of spores and living dust that the winds carry in the air far above. [DISCLAIMER: this book was sent to me by the publisher for an endorsement].

Adrian Tchaikovsky: Children of Time BEWARE There are

Adrian Tchaikovsky: Children of Time BEWARE There are spiders spoilers spiders. Generation starship Gilgamesh is the last hope of humanity to flee a dying Earth in search of a new home. Eventually they discover a gorgeous green planet that had been terraformed by an outpost of the long-gone human empire, watched over by a half-mad quasi-human guardian determined not to let any human land there and spoil her experiment in generating new sentient life. The life that arises, however, is not quite what the guardian — and the desperate crew of the Gilgamesh — had expected. Who will win the ultimate battle? Terrific, thrilling, madly inventive hard SF adventure. Moving immediately on to the sequel…