- Surprising conversations with the Vicar Part IV:

1 The Lord said to me again, ‘Go, love a woman who has a lover and is an adulteress, just as the Lord loves the people of Israel, though they turn to other gods and love raisin cakes.’

Erika: What does God have against Garibaldi?

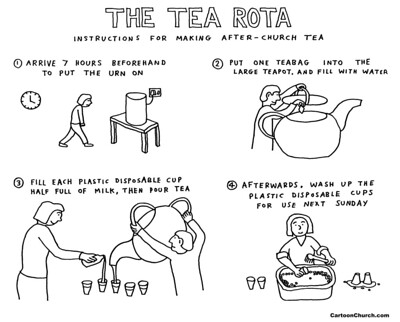

- The week after Holy Week, and about a month into my new parish administrator job. The rest of the staff team are on holiday. I am holding the fort alone. First I fall out with the printer, then I break the shredder, and by the end of the week I have entered into a state of impaired communion with the door entry phone. Through tears of frustration and with cyan ink everywhere I discern that, whatever the future holds, I am not called to a glorious career in church administration.

- Theology and technology become a running theme: I am not alone with the printer thing. Clergy empathise. It is well know, they inform me, that printers are cursed by witches before dispatch. James adds that if Jesus was to return and cast out demons, he would not cast them into swine but into printers. Another clergy friend suggested that the rapture has happened and we’ve all been left behind, with the printers. I consider writing it all up: Is heaven paperless? Clergy theories and printers.

- James forwards me the link to the diocesan vocations day. I guess it’s time.

- I am asked

How was the vocations day?

I reply

Magical 💕

- Resurrection and Tacos: Easter Lunch for the St Mary’s 20s and 30s crowd.

Resurrection and tacos: Easter lunch in the crypt

- The readings for the fifth Sunday after Easter are thrown at me with minutes to go until the service starts. I run around the church trying to find someone to teach me how to pronounce “eunuch”.

- Struggling with the Easter Bunny Bench Press Max Out, an in-house bench press event at the gym which takes place on Easter Saturday. My coach says I seem irritable. The incongruity bothers me. Jesus is harrowing hell, and I am maxing out my bench press.

- Landing a regular gig leading morning prayer.

- Landing a second parish administrator job. I was not prepared for the extent to which I would fall in love with the parish.

- Developing core skills for church life: how to print an A4 document as a double-sided A5 booklet.

- Developing core skills for church life: how to tell generous parishioners that we as a church cannot use their donations of, variously, broken cookware, opened food packets, old clothing. I master the church worker’s refrain: it’s a church, not a bin.

- Developing core skills for church life: how to create a poster for a Bible study day, in moments, in Canva.

- People asking me within weeks of meeting me, whether I had considered ordination. This is getting real.

- Theology, technology and miscommunication. I again consider writing up my experiences. Is email fundamentally incompatible with grace? Case examples and theological reflection.

- Theology, technology and miscommunication. I wonder if I could put together a special issue. Can we recreate the early church in WhatsApp groups? Social connection among recently converted Christians.

- Theology, technology and miscommunication. I wonder what it would take to implement a “pray and send” button as a plugin to Outlook. I wonder why this has not been done before.

- Theology, technology and miscommunication: collected papers. What counts as unacceptable before God? The occult, and being in charge of who is permitted to hire the church hall.

- Coming to terms with the reality that parish administrator and some kind of ministry are two different callings. I want to be giving the people communion, and all I have to give them are badly formatted hymn sheets. It is time to move on.

- Only at Imperial: At the start of a Carols by Candlelight service, the building is in darkness. Each of the hundreds of congregation members holds an unlit candle. The priest lights a candle and uses this to light the candles of two members of the congregation. They in turn light the candles of a couple of people around them. A wave of light gathers pace as it sweeps the church. The student sat next to me leans in and observes:

exponential growth

- Someone asks me if I know Rosemary Lain-Priestley.

Yes

I say.

She would remember me. We had the same hairdresser for a while back there.

- Being asked whether I want to train as communion assistant, administering the chalice.

It’s alright if you cry, right? If your tears get in the cup they get sanctified? Right?

- My first and likely last contemporary Christian worship band concert, For King + Country perform their Christmas album at indigo at the O2. Milling around the Millennium Dome trying to find the queue for the gig, I spot a couple wearing matching sweatshirts. Their outfits declare

Jesus: He’s the reason for the season.

I’ve found my people, I think. Then I pause: These are my people?

- Past lives haunt this new one. Monthly I attend a bellringing practice that takes place moments from the new GSK headquarters in the centre of town. In early months of the year I must pass the branding hoardings; by the end of the year I am walking past the newly opened building. I glance at the security passes of the employees finishing their working day and commuting. I am searching in vain for my old self.

- Bellringing milestones: ringing my first quarter peal, and my second, and my third.

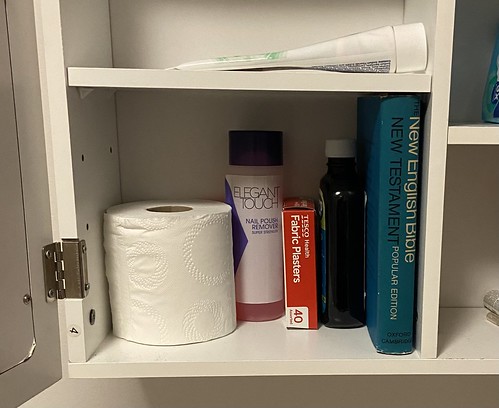

- Finishing reading the Bible in a year.

- Ringing in the New Year. The past two years have been extraordinary. I pray, and I keep walking.

Happy New Year.

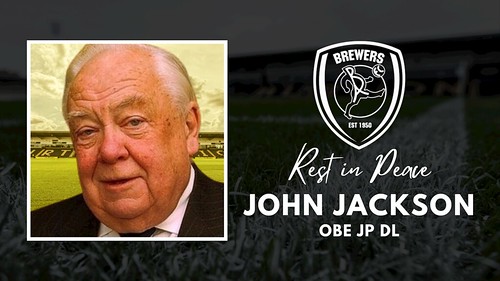

Lives in lanyards.

The band for my third quarter peal. Read about it on Bellboard.