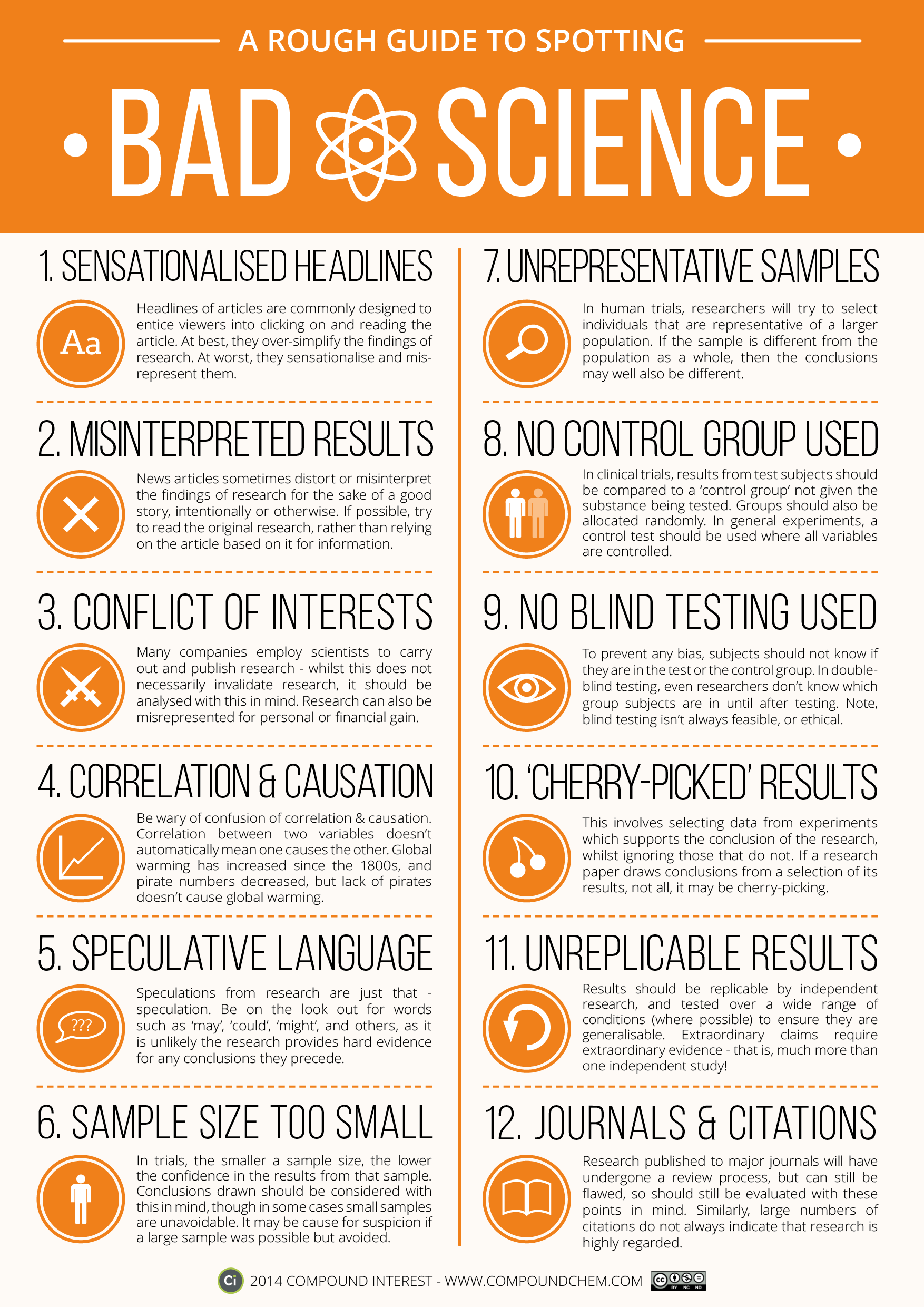

On the Interwebs – I have seen several links to this helpful PDF on How to spot bad science – a rough guide.

Learning how to sniff out bad science – or really bad science reporting which is what this guide seems to be aimed at – is important. As most folks know, after cold fusion and arsenic in DNA, spotting when there is something that smells funny, should be part of any scientist’s or science aficionado’s tool kit.

To be abundantly clear, I think detecting bad science (and there is much of it out there) is a good thing. I think, for the most part, this quick guide is also a good thing – especially with advice on being wary of ‘sensationalized headlines’ and being cynical about everything you read and believe.

However, sadly, this rough guide is too simplistic in some of its advice, advice which is a bit too vanilla to be of much use when reading a scientific report.

Take for example ‘unreplicable results’. This is a big warning for bad science, clearly, but how exactly can you detect this in an NEW article? If you are reading a scientific press release it is likely a fresh set of exciting results, which no one has had the chance to try and replicate yet. Also you have to be a bit cautious between ‘unreplicable results’ and ‘results which haven’t been replicated yet’. The former is bad science, the later may be opening up an new area of science that is somewhat outside the paradigm. Or in other words beware of the Physics-is-dead syndrome.

What about ‘misinterpreted results’? Another big warning sign for bad science but incredibly difficult to detect, especially when reading a scientific study outside your area of interest. Misinterpretations abound in the literature, often because at the time they don’t seem like misinterpretations – it only becomes clear when some new data pops up, often well into the future.

Then there is ‘conflict of interest’. We all have conflicts of interest. It is impossible to be a human and not have a conflict of interest somewhere. The warning in the guide is probably to flag up tobacco-isn’t-that-bad-for-you arguments by the major cigarette companies but, importantly, it’s worth remembering that much good research takes place in industry. R & D laboratories which are privately funded are not all hell-bent on misleading the public.

The rough guide advice I found the worst, hands down, was ‘speculative language’ where the guide states:

Speculations from research are just that – speculation. Be on the look out for words such as ‘may’ ‘could’ ‘might’ and others, as it is unlikely the research provides hard evidence for any conclusions they precede.

The first tautological statement notwithstanding, Really?!? Science rarely presents exact conclusions – usually research opens up more questions than it answers. Saying ‘we see this’ and ‘we think this means that’ is perfectly acceptable in scientific literature. In fact it is the bread and butter of many research publications. I am far more dubious of a study which says ‘we see this, therefore it absolutely must mean that’. Most scientific studies are a process of slowing marching forward (and back again and then sideways a bit, oops and then we all fell in the lake) to make new, even if they are small, discoveries. It’s important to be speculative, otherwise the whole shebang would get rather boring and dogmatic.

Hi Sylvia,

Thanks for taking the time to comment on the graphic. As I stated on my site when I originally posted the graphic (a post you may have missed, since I note you’ve credited the Lifehacker article), it is definitely intended to be a rough guide, and in no way comprehensive. In fact, I created it after researching aluminium chlorohydrate, and becoming frustrated with the multiple links to cancer, citing research studies which ticked several of these ‘bad science’ boxes – didn’t really expect it to gain so much traction online!

The nature of the graphic means some of the points have had to be condensed in a manner that of course simplifies them – hence the ‘Rough Guide’. The aim is more to get people genuinely considering these points, and looking into them themselves – in reality, each could probably use their own full A4 poster, but I doubt that’d prove as popular 🙂 I’d at no point say that just fulfilling one of the criteria on the poster automatically makes a study ‘bad science’, but rather that they should be borne in mind.

With the ‘unreplicable results’ point, you are of course correct that in the cases of research which is treading new ground, it may well be the case that there has been limited opportunity to replicate the results independently. That said, I’d say it’s still something worth noting, because there have certainly been cases where results in studies have not been possible to replicate in subsequent others.

The speculative language point, again, falls victim a little to the limitations of space in the format. Here I was trying to get more at the overuse of speculative language, and stretching of research findings to essentially unsupported conclusions. I perhaps should have tried to find space to clarify this, as I’d definitely steer even clearer of a study that stated its conclusions as unequivocal fact!

Hope that clears a few of the points up; I think the comments section of the original post is worth a read, as several people have made some good points, some not dissimilar from your own.

Hi –

thank you for the comment. I think most of your rough guide was good. But I still think trying to condense these things down is problematic – but fair enough for trying to do it quickly – I get that as I too have had some issues simplifying things too much …

As I said in my post – the only one I have serious objection to is the speculative thing – maybe it’d be an idea to change it to ‘unsupported conclusions’ ….

One of the worst things in scientific literature I think is the statement ‘it is now well know that’ – and then when you go back and check the references it isn’t well known at all! It is just the authors cited have speculated (which is fair) and have been quoted as ‘the gospel’ even though that isn’t true – or what the speculators said in the first place! That drives me nuts – and there is absolutely no way to get that point into an infographic

Nice website by the way

I’ve also updated the link to the rough guide to come from your website

Thanks again for the comment

The idea of changing it to ‘unsupported conclusions’ isn’t a bad one – definitely a good idea for the next revision, so thanks for the suggestion.

There’s a difference isn’t there between “unreplicable” (badly designed or reported experiment making replication impossible) and “unreplicated” (we haven’t got round to it yet)?

Yes definitely – but it is not so easy to spot the difference when reading the literature … Especially if it’s something you aren’t so familiar with

One of the most reliable indicators of bad science (or non-science) is reliance on induction rather than the hypothetico-deductive method.

Induction is “mechanical” extrapolation from data. The hypothetico-deductive method is essentially the guessing of a hypothesis, followed by the deducing of some of its observational consequences, followed by observation to check whether those predicted consequences are indeed as predicted.

Couldn’t agree with you more, Sylvia, especially regarding the last point!

It is incumbent on scientists to speculate and propose the best, most suitable, and simplest model that the data point toward (Occam!). What’s important, as you nicely note, is the scientist clarify when the discussion moves from the realm of what was observed to the speculative area of what the possible model is – based on the best evidence available to date.

I think there should be a category for ‘urban legends’ – that is, so-called science reported, usually in a tabloid, whose sources are deeply murky and possibly even unpublished, but which seem to get recycled again and again. I offer my own modest example http://occamstypewriter.org/cromercrox/2013/04/11/tts/

Came to you by way of a link posting in the 4/30/’14 “Big Think” article “How to Spot Bad Science” by Neurobonkers. Your critique of a generally useful poster is spot on. Just wanted to send you a fan letter and give you notice that you’ve added another reader.

Thanks! Thank you for reading as well!

Great piece, Sylvia.

Love this as a starting point for educating lay persons about how to consume media reporting on science.