Yes, it’s that time again, when I list the books in the year just passed that I have most enjoyed. I’ve been doing this since 2014. That’s when I started noting authors and titles of books I’d read in a small notebook given me one Christmas by my friend H. F. of Edgefield.

This is an interesting exercise. Looking back, I find titles I enjoyed immensely at the time, but forgot about more or less immediately after I’d read them, rather in the manner of the sex life of the Brachiosaurus, its tiny brain being so far from its generative organs such that if it had sex it forgot about it afterwards.

This is no reflection on the books, but, perhaps, my ageing mind; that I read an awful lot of things; and that my mind is always full of extraneous clutter. However, some of these books were both enjoyable and memorable, and books need to be both to make the list.

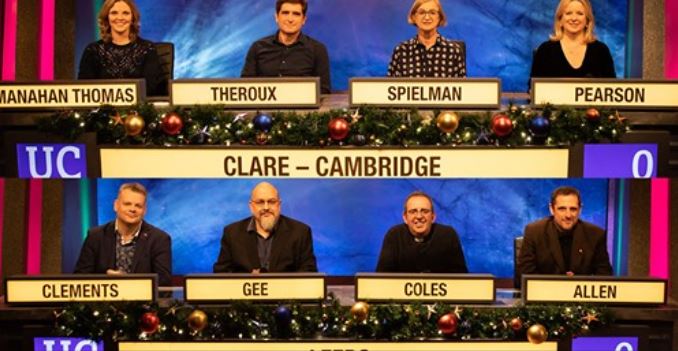

This year I have read 41 books. Here, in no particular order of appearance, as they say on the game shows, are the ten I’ve most enjoyed — and remembered. It’s spoiler-free, in case you want to read them yourself. I have included links that allow you to learn more. At the end I’ll reveal the overall Best Read. Now, I have to say that this is my opinion. Please feel to disagree.

Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman, Good Omens – Something or other by Neil Gaiman usually features on my end-of-year list, and this year is no exception. This is a first appearance by Pratchett, however. I read The Colour of Magic, his first Discworld novel, many years ago, and enjoyed it. But when I looked up there seemed to be a superfluity of other such novels. So many books, so little time. That, and the peculiarly ardent nature of its attendant fandom, put me off. I was stimulated to read Good Omens by the imminence of a rather good televisual emission, and I managed to get the book in first. Gaiman and Pratchett wrote the book before either author had become famous. You’d never know this, however: for all its freshness, it is achieved with consummate skill. It started with an idea from Gaiman who mused, as only Gaiman can muse, about what would happen if one of Richmal Crompton’s Just William stories crashed into the Book of Revelation, with all the opportunities for humor that such a collision would engender. Wickedly, laugh-out-loud funny. And while on the subject of Neil Gaiman…

Neil Gaiman, Anansi Boys – Another of Gaiman’s books in which real gods come down to Earth, and mayhem ensues. But where American Gods is cinematic, Anansi Boys is a sitcom, with both sit and com. Here’s the sit: you are a regular klutz of a bloke whose aim in life is to be conventional and quiet. One day, though, your long-lost brother appears. He looks just like you, but is much more fun. He steals your girlfriend and turns your life upside down. That’s the ‘com’ part. For, you see, you are both the sons of Anansi, the African trickster God, who has lately been spending his retirement quietly fishing in the West Indies. Until…

Bram Stoker, Dracula – You’ll both realize by now that I am as fond of a good gothic yarn as the next man shuggoth person, but I had never read this one. Less a good read than an exercise in peeling away all the accumulated layers of schlock and hoar that have submerged it. All the elements are there, however: a crumbling castle in Transylvania; a bloodsucker that accretes the souls and personalities of its victims; and Van Helsing, the charismatic vampire-hunter recruited to hunt it down and destroy it. What is perhaps unexpected and surprising is that it’s written as a series of letters and journal entries from a cast of more or less unreliable narrators. And what a lot of old tosh it is. Dated, sexist, over-written, but, like many in the gothic genre, for all its literary faults it exerts a residual psychological power.

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five – Many writers who served in war became so traumatised by their experiences that they could only get it out of their systems by resorting to the fantastic. From the Great War there was, of course, Tolkien (The Fall of Gondolin) and Stapledon (Star Maker). From World War Two there was Kurt Vonnegut, and Slaughterhouse Five. The novel tells the story of a war veteran, witness to the bombing of Dresden, and his entire later career as a humble small-town optometrist, written as if all his life experiences were lived at once, which is the perception of time experienced by an alien race. That it is weird one can take for granted. That it was published in 1969, during the Vietnam War, pegs it as an anti-war novel. It is therefore a product very much of its age, but despite its subject matter it has a lightness of touch that’s almost ethereal.

Samanth Subramanian, A Dominant Character – Every so often I have the privilege of being asked to review a book for the Literary Review, and this was one such. It’s a biography of John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964), pioneering evolutionary biologist, consummate and prolific author, and, in his time, a popularizer of science as well-known as Alice Roberts or Neil DeGrasse Tyson are today. He was also a complex character. Born into the Scottish aristocracy, he became an active member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, and eventually quit Britain to set up a research institute in post-independence India. Haldane’s life was such a Boy’s-Own ripping yarn — and lived so much in public — that it’s amazing that he’s rarely been the subject of a biography. This is only the second (the first was a hagiography written by one of his final students, in India) and is likely to be definitive. And while we’re on the subject of biography …

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton – Offspring, eh? When they are small they are a sauce tzores source of effluvia comfort and joy. When they get older, they enthuse about the various manifestations of popular culture with which they come into contact. If it hadn’t been for the Offspring, I might never have experienced the unalloyed delight of such things as Lady Gaga, The Mandalorian, Peaky Blinders, Game of Thrones, JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure or the DirtyFilthySexy club night, to name but nine three six. One of the most enduring of such discoveries is Hamilton, the hip-hop musical written and initially performed by the remarkable songwriter and human being that is Lin-Manuel Miranda. The idea came from this book, which Miranda had taken to read on the beach. And what a great read it is. Hamilton came from the storm-wracked island of Nevis (‘A forgott’n spot’n the Caribbean’, as the musical has it) to become one of the Founding Fathers of the U. S. and A. He was a revolutionary, soldier, statesman, autodidact, founder of the United States Treasury, creator of advanced financial systems of debt and credit, Washington’s right-hand man, husband, father, lawyer, philanderer, heart-throb, dandy, social climber, abolitionist, prolific essayist, newspaper magnate, pamphleteer, founder of the U. S. Coastguard, duelist, and, for all I know, the winner of the Mrs Joyful Prize for Most Advanced Student in Knitting. These days we take the founding and rise of the U. S. for granted. It is easy to forget that at the beginning it was weak, fragile, and its system of government was a loose ball, up for grabs by anyone brave to pick it up and run with it. Hamilton’s idea of an advanced, aspirational, industrial, centrally controlled federal nation was in opposition to Jefferson’s dream of a loose association of agrarian states supported by slave labor (indeed, Jefferson comes out of this story as a complete sh1t). Many of the divisions in modern US society might be traced to this mutual antipathy. I learned a great deal about the early history of the U. S. from the musical. I learned even more from this book. If Mr Miranda is reading this, I suggest that his next beach read should be The Cuvier-Geoffroy Debate by Toby Appel. Just a thought. And while on the subject of things introduced to me by the Offspring…

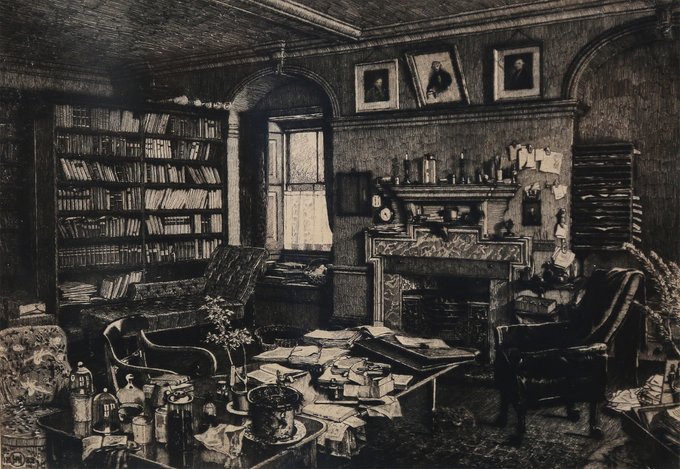

Erin Morgenstern, The Starless Sea – Morgenstern’s debut novel The Night Circus was my top read of 2014 and would still get a place in my all-time top ten. This, the follow-up, has been a long time coming. It has the same richly evocative atmosphere as The Night Circus, but is both darker and much harder to unpack. It’s very hard to describe, but if forced to do so in a phrase, it’s a fantasy spy thriller about books and reading. Think of a cock-eyed mashup of Borges, James Bond, and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas, but set in Mr Magorium’s Wonder Emporium, if Mr Magorium had set up an extensive library. In a sweet shop. Underground. With bees. This is one I shall enjoy re-reading. And while on the subject of re-reading…

Olaf Stapledon, Star Maker – This is one of my favorite books, which I had occasion to re-read this year as I needed to quote it in my fifthcoming forthcoming tome A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth. It’s arguably the boldest, most ambitious work of speculative fiction ever penned. For all that the book is quite short, it covers no fewer than 400,000,000 years of cosmic evolution. The entire story of humanity occupies a couple of short paragraphs. But it’s no space opera. Stapledon, a lifelong pacifist who served in the Friends’ Ambulance Service on the Western Front, wrote it in 1937 as the world once more slid into war, as a philosophical exegesis on the significance of individual action that might seem hopeless or negligible when measured against the scale of the cosmos. Absolutely unforgettable.

Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life – As the autumn closed in and fungi started popping up everywhere, this book landed on my desk: another commission from the Literary Review. It’s an engaging tour of fungi and how they shape our lives. Sometimes it’s so exuberant that one suspects that the author has been at the psilocybin, but it’s never less than entertaining.

… And the Overall Winner goes to …

… roll of drums …

Vikram Seth, A Suitable Boy – This cyclopean doorstep had been glaring down at me from the shelves for years, but I had been daunted by the sheer size of it. It’s more famous for being one of the longest single novels ever written in English than for anyone actually having read it. I was prompted to try, as I sometimes am (qv. Good Omens) by a televisual emission, in which this sprawling edifice had been condensed into six one-hour episodes. Although the drama was gorgeous to look at, it was sometimes hard to keep track of who was related to whom, but by the end I had gotten the gist. With some vague idea of the story, I pitched in. And, do you know what? The water was lovely. The story starts in 1951 and is set over a period of eighteen months or so, in India, which has just become independent and has undergone the trauma of partition. It starts with the many worries of Mrs Rupa Mehra, who is trying to find ‘a suitable boy’ for her student daughter, Lata. The daughter is as mild-mannered as her mother resembles a spiced-up Mrs Bennet. But the story broadens out to encompass the lives of Lata’s cousins and their friends, whether Hindu or Muslim, to give a bright yet occasionally bewildering picture of a society of immense complexity built on ages of tradition, which is, at the same time, trying to find its place as a new and modern nation. Given its place in the literary canon it is a surprise to learn that it is as easy to read as, say, a large fantasy novel, though better written than most. After all, Seth gives no quarter to any reader who, like me, knows no more than the basics of Indian food, festivals, religions, castes, languages, history, geography, climate, politics, styles of dress, musical instruments, and so on, so I found myself having to look things up constantly. One is often confronted by such culture shock reading a large and complex novel set in some imagined world, and, once I had grasped that, I sailed along. It was one of those books that I raced through, and mourned once I had turned the last page. And, who’d have thought it, the televisual emission grasped the essentials extremely well.

Greatest Hits of the Past

2014 (45 books read) – Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

2015 – (41) Dan Simmons – Drood

2016 – (43) Hilary Mantel – Wolf Hall

2017 – (34) Ursula K. Le Guin – The Left Hand of Darkness

2018 – (56) J. R.R. Tolkien, The Fall of Gondolin

2019 – (18) Brian Catling, The Vorrh