A few weeks back I was a roomful of senior librarians, having Important Conversations about Publishers (ICP). More recently I sat and listened to a number of ICPs at the UKSG Conference – bookended by talks from Ann Rossiter and Cameron Neylon, each with important things to say to publishers. So far so momentous: the tectonic plates of scholarly communication are shifting and no-one is quite sure what the end result will be.

It is surprising to reflect that ICPs are a relatively recent phenomenon. Until about twenty years ago libraries’ key relationship was with their serials agent rather than with any publisher. I remember in about 1987 I had a visit from the rep for a major publisher and I didn’t really have much to say to him, certainly nothing in the ICP mold. Librarians back then did talk amongst themselves about publishers – mostly complaining about the daft things that publishers did to make librarians’ lives difficult. Generally the daft things relate to changes made to journals.

Journals can be confusing things. They differ from each other in myriad ways. They may be published monthly, weekly, semi-monthly, biweekly, quarterly, bimonthly, or at some irregular frequency (my favourite is sesqui-monthly). There may be split issues, combined issues; there may be volume numbers or not; there may be cover dates or not; the cover date may or may not correspond with the actual date of issue. We get used to all these things. And of course every journal needs its own title.

Changes can cause particular headaches for librarians, and for readers. Some changes are not too disruptive: a change in the frequency is only mildly confusing. Minor changes in title (adding a word or two) are not too troublesome, but major changes can mean that readers fail to find the journal unless clear signposts are in place to redirect from the old title to the new title (and vice versa). In the days of print libraries could put signposts in their catalogues and lists, and even on the shelves themselves. Now we rely more on publishers to put the signposts in their websites. It gets worse when journals merge or split.

Some journals create confusion by having multiple sections, almost amounting to separate titles. One prominent example is Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). Currently it has ten separate sections, but over the years other sections came and went. On ScienceDirect about 20 different sections (past and present) are listed in total.

The confusing thing about BBA is that there is a single sequence of volume numbers through all the sections. So volume 1804 might be in one section, volume 1805 in a different section and volume 1806 in a different section again. Elsevier, the publisher of BBA, had a number of journals with this kind of structure; Mutation Research springs to mind as another prominent one.

This complex structure created challenges back in the days when we handled print issues of journals. We needed to know which issues to expect and in which sections they would fall; we had to decide how to shelve the issues (by title or by volume number); we had to decide how to bind them (different colours for each section?). All this is pretty much a non-problem now, in the days of online journals. But, as noted already, we rely on publishers websites to provide easy navigation.

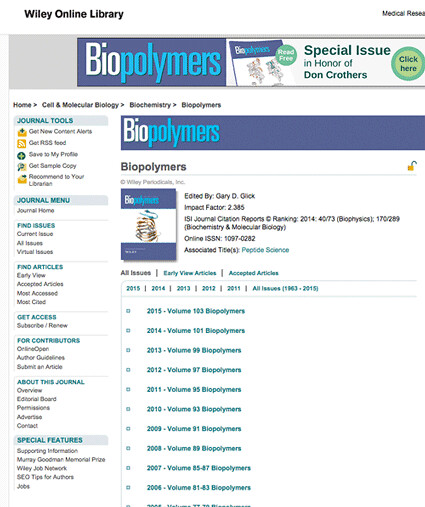

This week a confused reader came seeking assistance in tracking down an article in a Wiley journal, Biopolymers. The article was in Biopolymers volume 94. Someone sent him the reference in an email, so he went to the Biopolymers website to find the article, but could not see volume 94 listed there, thus he sought my help.

I wondered if it was perhaps a supplement volume, with conference abstracts, as these are sometimes published separately from regular journal issues. It wasn’t. As I inspected the listing of volume numbers on the website it struck me that only odd volume numbers were listed there, which seemed rather odd.

I was intrigued by this mystery. I searched PubMed and found the article listed there, then followed the link to the full-text and easily found the article on Wileys’ website.

So, I had the article but was still perplexed as to why I couldn’t see it (or any even-numbered volumes) on the Biopolymers web page.

Looking more carefully at the page for the article, I saw it had a large blue Biopolymers’ banner image at the top. But there was also a prominent red banner below it, showing the words Peptide Science prominently, and the word ‘Biopolymers’ in a smaller font running vertically up the red banner.

I looked up Peptide Science in Wileys’ alphabetical list of journals, followed the link and found all those even-numbered volumes listed, that were missing from the Biopolymers page.

In PubMed (and Scopus and Web of Science) all articles published in Peptide Science are listed as articles published in the journal Biopolymers. But on the publisher’s website, they are listed only under Peptide Science and the image of the cover clearly shows only the Peptide Science brand.

That seems a bit unhelpful to me.

I see that Peptide Science is the official journal of the American Peptide Society, so perhaps that is the reason it holds fast to a separate identity. It might be better to separate from Biopolymers more completely but I guess there is some brand advantage in associating with it.

In the world where we only ever click on a link, or follow a DOI, maybe it doesn’t matter so much. But if someone emails you a reference, or you scribble down a journal reference, and then go about trying to find it you will fail.

Publishers love to claim that everything they do is for the good of the academic community. But making it difficult to find articles, charging high prices for subscription journals, and putting barriers in the way of open access are all signs that this is an empty claim.