In which I am reminded that once stuff is in your brain somewhere cluttering it up, it can be pretty hard to get it out. Random bits of chess knowledge included.

It is probably another of those middle-aged things, but I find myself lately reflecting on the reasons why I might have got into particular activities that have been important in my life – including my line of work, of course, but also taking in hobbies and interests, like films and chess. Can one pinpoint influential people, like teachers, or authors whose books you read, or films you saw, that ‘pushed’ you in particular directions? Or can one pinpoint key moments?

Perhaps I will write another time about my path to becoming a second-generation scientist – though I have written bits about it in different places, I have never collected it all together. One for a rainy day (luckily we have quite a lot of those in Manchester).

My path to being a teenage chess geek (see my April Fool’s Day post) was undoubtedly far simpler – there was a chess boom in England in the mid 70s, and indeed worldwide. This boom could be attributed to one man, the late Bobby Fischer, and more specifically to his 1972 world championship match in Reykyavik against Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union.

The 1972 match was the only time, before or since, that chess was the top story on the nightly news bulletins. The reason was the extraordinary drama that surrounded the match, and in particular Fischer and his essentially solo crusade to take the title from the Soviet chess establishment. It made for the perfect piece of Cold War theatre, all the more riveting as it pitted a solitary maverick genus (Fischer) against an entire national system. The Soviet chess system was, of course, backed by the Soviet state from the early 1930s onward as a pre-eminent national symbol of the intellectual superiority (as they saw it) of the communist system. Chess was taught in schools and in youth clubs, and promising players would be picked out for intensive training from as young as 7 or 8 years old.

I distinctly recall that the first time I read about the Fischer-Spassky match was before it started, in the early Summer of 1972 when I was not quite eleven years old. As I remember it I read an article, probably in the Sunday Times, about Fischer, describing his lone path to being the challenger and also indicating that the match actually might not take place at all due to wrangles over conditions and prize money. After that, when the match actually began, I was hooked.

If you don’t know this history, you can actually see it in a documentary film which has recently been running in some of the art house cinemas in the UK, and will probably show up on TV before too long. I mentioned this film briefly in a recent chess-related post. It is called ‘Bobby Fischer against the World’, and, recounts – using interviews and a lot of archive footage – the story of Fischer’s rise, from 1950s child chess prodigy to the 1972 match, and his subsequent tragic decline into increasingly florid mental illness. Even if you know nothing about chess, the film is well worth a look. You can read more about it in a nice blog by Jonathan Calder over at Liberal England.

Now, one of the ways that you can see the influence of particular figures on you, in any arena, might be the number of their ways of doing things – their strategies – or even their mannerisms, that you can detect in yourself. Your parents are of course the ur-example of this influence on you, but picking up influences doesn’t go away even once you are an adult. For instance, young scientists are often advised to imitate the writing style of particular papers, or authors, or find themselves people whose written style appeals, to use as models. And the scientific fields one chooses to work in as a scientist are a product of influences too, notably perhaps from PhD and postdoctoral supervisors, but also from elsewhere. One’s working practises, either as a postdoc or a lab head, will also be in part a product of examples one either consciously or subconsciously follows.

In a complex game and pastime like chess, one of the ways that you can sometimes tell who your heroes among the great players were is, a little analogously, by your adoption of aspects of their way of playing. As it is hard to really imitate a great player’s overall style – especially if you are an average player yourself, as is typically the case – this influence tends to manifest itself most obviously in one particular thing, the choice of ‘chess openings’. These are the way that a chess game starts, sometimes extending for twenty or even more moves. [Chess-interested readers might just remember the Steves Caplan and Moss and I having an incomprehensible-to-all-normal-people discussion about chess openings back in the comments here].

Looking back now at my teenage chess-playing career, I see a fair few of Fischer’s chess opening preferences reflected in my own. I can’t recall whether this was conscious or unconscious – probably a bit of both.

The thing I find most intriguing is that, even thirty years on, little bits of this youthful influence tend to surface unbidden when some kind of memory association triggers them.

Here is an example.

Among the games of the Fischer-Spassky match, game 3 often gets written about as a crucial turning point. Fischer had lost the first game of the match by a gross blunder, and forfeited the second due to a protest about film cameras being present in the playing hall. Game three very nearly did not take place, and had to be played in a closed room with no spectators. In the game Fischer played a very risky idea, later shown to be ‘unsound’ (as in ‘leads with best play to an advantage for the opponent’) on his 12th move. However, Spassky mishandled the next few moves, failing to find the best response, and Fischer gained the upper hand and won. It was the first time he had even beaten the Russian, having previously lost to him four times over the course of a dozen years. Following this, Fischer won six further games to Spassky’s one to take the match and the championship.

Thanks to the wonders of the splendid java-driven internet site chessgames.com, you can play over the moves of Fischer-Spassky Game 3 here. The risky idea is at Black’s move 11 ..Nh5.

Now, when I started playing chess again earlier this year after my thirty year lay-off, I began by playing against the online chess programme Shredder. In one of these games, I found myself a bit stuck for a plan of action as the opening transitioned into the middle game. This was not, by the way, a chess opening I used to play in my teenage chess years, so not one I knew terribly well.

And then suddenly the thought popped into my head: didn’t Fischer famously play …Nh5 against Spassky in a position a bit like this?

So I played …Nh5.

As far as I can recall, I had not played through the Spassky-Fischer game in more than three decades. So where had that nugget of information being hiding?

Which goes to show, perhaps, how deeply ‘burned in’ those early influences and memories can be.

Anyway, I have given my game with the computer below, for obsessed dedicated chess-ists, along with a couple of other of my more recent ones.

And do keep an eye out for the film.

—————————————————————————————

White: Shredder Medium Online Black: Austin Blitz game May 2011 Modern Benoni Defence

1. d4 Nf6 2. Nf3 e6 3. c4 c5 4. d5 ed: 5. cd: d6 6. Nc3 g6 7. Nd2 Bg7 8. e4 0-0 9. Be2 a6 10. a4 Nbd7 11. 0-0 Re8 12. Qb3 Nh5?! (The Fischer idea, dimly remembered across the three decades in between) 13. Bh5: gh: 14. Nc4? (Nd1-e3 neutralizing Black’s K-side attacking chances is the accepted plan to maintain an advantage) Ne5 15. Bf4 Qh4?! 16. Nd6:?! Qf4: 17. Ne8: Nf3+?! 18. gf: Be5 19. Rfc1 Bh3 20. Nf6+ Qf6: 21. Ne2 Qg5+ 22. Ng3 h4 23. Qb7:?? (f4!) Rb8 24. Qa6: Rb2: (…hg:) 25. f4 Bf4: 26. Rcb1 hg: 27. hg: Rf2: (unnecessary – Bg3: wins) 27. Kf2: Qg3:+ 28. Ke2 Bg4+ 29. Kf1 Qf3+ 30. Ke1 Qe3+ 31. Kf1 Bh3 mate

Also in chessworld, I recorded the first competitive game loss of my chess comeback last month just before we set off on our holiday. The game, with minimal comments, is below. It was an interesting and tense struggle, with (fairly obviously) a lot of mistakes on both sides. I finally lost on time, having survived a frankly lost position earlier via my usual desperate tactical swindles and bluffing. In the final position I think I might well have won had I had another five minutes on the clock. Hey ho.

DH – A Elliott Manchester Summer League game Aug 2011 Reti-King’s Indian

Time control: 1 hr each for first 30 moves, then 15 min each for all remaining moves

1. Nf3 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. b4 Bg7 4. e3 d6 5. Nc3 e5 6. Bb2 0-0 7. Qc2 Re8 8. Be2 a5 (possibly …c6 first) 9. b5 Nbd7 10. a4 e4 11. Nd4 Nc5 12. 0-0?! h5? (Black should play..Ng4 at once. As played he never gets a piece to g4) 13. f3! Bd7 14. fe: Nfe4: 15. Ne4: Re4: (already mostly deciding to sac the exchange on e4, but the more flexible …Ne4: should probably be preferred) 16. Rf2 Qe7 17. Raf1 f5 18. Bf3 Rae8 (offering the exchange to keep the pieces active, but almost certainly not enough) 19. Be4: Ne4:? (the Kinght is inevitably chased away by d3, so fe: was better) 20. Re2! c5 21. Nf3 Be6 22. d3 Nf6 23 Bc1? b6? (last chance to play a piece to g4) 24. h3! Nd7 25. Kh1? d5 (something has to be done to try and get some counterplay) 26. e4! fe: 27. Ng5? Bf5! 28. de:? (cd: should win) de: 29. Qd2 Bd4 30. Qf4 Nf6 (With seconds only to spare, but the reprieve is only temporary with a 15-min rapidplay finish) 31. Nf3 Qd8 32. Nd4: cd: 33. Qg5 Nh7 34. Qg3 Qb8? (…Re6) 35. Bf4 Qc8 36. Rfe1 Qc4: 37. Kh2? e3 38. Qf3 Be4? (better ..Bd3 straight away) 39. Qg3 (now with a threat on g6) Bd3 (and now …Nf6 was better, getting the Knight back into play) 40. Be5 Qd5 41. Bc7 Nf8? (Very passive. Again … Re6) 42. Bb6: Be2: 43. Re2: Qc4 44. Qf3 and Black lost on time.

Finally, here is a casual game from my latest weekly trip to the chess club. It was played at 15 minutes a side (each player has 15 min thinking time for all his moves).

White: AE Black: KS 15 min rapidplay game Sept 2011 French Winawer

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. e5 Ne7 5. Bd3 c5 6. a3 cd: 7. ab: dc: 8. bc: Nc6 9. Nf3 Qc7 10. Qe2? Nb4:! 11. 0-0 Nd3: 12. Qd3: Bd7 13. Ba3 a6 14. Rfe1 Bb5 15. Qe3 h6 16. Bd6 Qd7 17. Nd4 Bc6 18. Qg3 0-0 19. Qh4 Ng6 20. Qh5 Re8 21. Re3 Rac8 22. f4?! Nf4: 23. Qg4 Ng6 24. Rf1 Qd8 25. Raf1 Nh8

A slightly non-standard kind of French Winawer – 4 ..Ne7 and 6 ..cd: are rare continuations (instead of the more common …c5 and ..Bc3:) presumably to try and get off the beaten track. Rather than 8 bc: it would have been better to play 8. Nf3!, sacrificing a pawn for speedier development after (e.g.) 8 ..cb: Bb2:. My 10. Qe2? blundered a pawn, though in return I got quite a grip on the position, especially the Black squares and the a3-f8 diagonal, and a strong Knight on d4. And 22. f4?! drops a second pawn, though the open f-file is some compensation. I may have got some of the move order slightly wrong between moves 19 and 22 – not absolutely sure, as I wasn’t writing down the moves and had to reconstruct the game from memory afterwards. Anyway, the most interesting point was after Black’s 25th move:

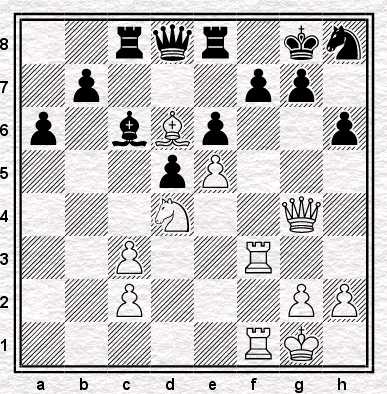

- Position after 25.. Nh8

White has an attack on the K-side, and Black’s f7 and g7 are weak. The question for White is how to try and press home the attack. I now played:

26. Rf6?!

What they used to call a ‘coffee house’ move – a bit showy, and partly played for surprise value, but objectively not very good. It sets the trap that Black now falls into – luckily for me – but if Black plays the correct 26 ..Kh7 then White has to retreat the Rook and the attack is neutered. The right move for White was the rather more straightforward 26. Rg3., when if 26.. Ng6 27. Rf7:!, or 26 ..g6 27 Qh5. Best for Black after 26. Rg3 would probably be 26…Qg5, though after 27. Qf3 Black would have to find another square for the Queen and White would still have good attacking chances.

26 …g6?

– missing White’s next, after which, if 27..Nf7: then 28. Qg6:+ wins.

27. Rf7:! Qg5

28. Qg5:

Obvious, but not the best. The surprising 28. Ne6:! was much better, since if 28 ..Qg4: 29. Rg7 is mate, and 28..Re6: 29. Qe6: is winning for White.

28 ..hg:

29. Rf6 Bd7

30. R1f3

Objectively this position is fairly even, though White’s pieces are much better placed. 30. R1f3 protects the c3 pawn, but doesn’t actually threaten anything much. However, Black was very short of time and also a bit shaken after having missed 27. Rf7:, and played several poor moves.

30 ..Rc4

Not bad per se, but probably in a time scramble it was better not to allow White the obvious check on f8.

31. Rf8+ Rf8:

32. Rf8:+ Kg7

…and Kh7 looks safer here, for reasons that become apparent in a move or two.

33. Rd8 Bc6??

The losing move and an obvious blunder, leaving the e-pawn en prise (with check) and putting his King in danger. By now he was down to his last minute or two. 33. ..Bc8 is the move to hold everything – the B then covers e6 and is protected by the R on c4, with the position still level.

34. Ne6:+ Kh7

35. Ng5:+ Kg7

…Kh6 was the last chance, though White would still be clearly ahead.

36. Bf8+ Kg8

37. Bh6+

And Black resigns, as it is mate next move.

Facinating blog, Austin–especially for us chess aficionados.

However, having thought about this a lot, I am somewhat inclined to disagree. I am well aware of Kasparov’s book “How Life Imitates Chess” (http://www.howlifeimitateschess.com/). To me it seems, at least as a very average player, that my strategies are designed to hide my most glaring and embarrassing weaknesses. Not having the time to spend poring over opening manuals and memorizing book lines, I seem to have chosen a very specific defense as my favorite that will allow me to avoid getting drawn into many of the openings about which I know little about. That is my main reason for choosing the Caro Kann.

An additional reason is the “closed” nature of the game that often ensues. Younger players (and face it, statistically I’m far more likely to encounter someone below my age over the board) yearn for the fast and wild play that would get me into trouble. My engine doesn’t run fast enough. So I prefer to keep things closed, and slow, and with fewer complex options.

But is this who I am in life? Perhaps, but I don’t see it that way. In science, I would prefer to think of myself as someone with supreme curiosity, willing to take calculated risks–and if nothing else, at least being able to be absolutely up-to-date at whatever I’m doing. Perhaps that’s why chess is so frustrating for me–if I could treat it scientifically, I might have a shot at really getting better.

But alas, work, writing, blogging. And while chess is still fun, it just doesn’t rank up there with my other occupations. But don’t tell anyone…

Thanks, Steve.

I guess it may be different for older players – perhaps we have a bit more insight into our own chess ‘style’, while youngsters (as you allude) are more likely to have a way that they want to play, whether that actually suits their particular strengths or not. When I was younger I think I was definitely better in blocked ‘slow maneouvering’ positions than in open tactical slugfests – but what I wanted was to be able to play heroic sacrifices like Mikhail Tal.

Of course, it was Emanuel Lasker who is often credited with the idea in chess of

– i.e. trying to work out, not what was the absolutely right move/opening, but what was the best move/opening to play against that particular opponent on that particular day. One of the interesting things about Fischer was that he was very much a:

– type of player for most of his career, and noted for his (related) dogmatic approach to openings (always playing 1 e4, for instance). It was only in the match against Spassky that Fischer finally seemed to get beyond this dogmatism, e.g. playing the Queen’s Gambit as white (for the first time in his chess career) in the famous Game 6 of the match.

Anyway, I agree that it is wise to choose openings that suit one’s style / play to one’s strengths. The tricky bit (which I struggled with in my teenage playing days) is to work out precisely what one’s strengths as a player are..!

For me, at least, in chess “strengths” can be defined as “less major weaknesses.” Since I am a slow thinker and hopeless at blitz (can’t even describe the “won” games that I threw away not knowing how to close the game in time pressure), any line that leads to limiting calculations is “less of a disadvantage.”

Of course you are absolutely correct about Lasker–and a real chess player (not to mention best ever player not to be world champion) knows how to play ALL styles, and can flow freely from a closed to open style if there is an advantage to be gained. No more the days of Morphy with open play vs the days of Steinitz and closed games. Whatever is there, the pros will take it.

As for Bobby–I guess that’s a great lesson. If one is entirely dogmatic, this makes the element of surprise exponentially higher when one actually sheds that dogma!

Hope to have a run at your games over the next couple weeks, but no promises! My PC laptop went belly-up, and now I don’t even have access to “Fritz.”

I think that’s true for all us ordinary chess mortals, Steve! Certainly is for me.

Lasker actually was World Champion for an extended period – one of the longest, in fact – though he didn’t always take on his strongest opposition. In those days there was no official system of challenges, and challengers had to ‘persuade’ the Champ that they had raised enough money to make it worth the Champ’s while to put the title on the line – oddly like boxing now.

– is a fascinating discussion. Limiting it to the postwar period, the remarkable Viktor Korchnoi, who turned 80 this year but is still playing, has a claim, but for many years the ‘consensus choice’ was the great Estonian player Paul Keres. And David Bronstein, one of my favourite chess authors, is another who would be in the mix, at least in my opinion.

Oops– I mixed up with Lasker. For some reason I thought that he was never officially crowned world champion. Thanks for the correction.

BTW, did you ever read “The Yiddish Policeman’s Union”? There’s a fair bit of chess-related folklore in that novel (not to mention that someone identified as Emmanuel Lasker is found murdered at the beginning of the novel. It’s a bit “over the edge”–on the premise of what would have happened if in 1948 Israel had been destroyed in the War of Independence, and the US had granted the Jews a homeland in Alaska, but entertaining.