I’ve decided to separate the actual chess GAME I played last week, and that I was talking about in the last post, into a separate post here. The main reason for this is that specifically chess analysis-related comments can now go here, while anything else can go on the previous post.

So… arriving for my second competitive league chess match last Tuesday, I was shocked and appalled to discover we were playing a local junior club.

I say ‘appalled’, of course, because no adult player likes playing against junior players. And I ought to know, since I was, throughout my playing days in the 70s, the junior.

There are various reasons adults dread playing juniors in chess. One is that young players usually play incredibly quickly, making it all look terribly easy, while you are desperately trying to kick-start your ageing synapses.

Another reason is that you never know quite how good junior players are (since they tend to improve rapidly in their teens), but they are usually far better than you are told they are.

A third reason is that you are on the proverbial hiding to nothing.

Win the game, and someone will say: ‘Well, s/he was only a kid’.

Lose the game, and you lost to…a kid.

Finally, there is the worry that losing to a player over thirty years younger than you will focus your mind yet again on the topic of ageing and mental decline. Not a comfortable thought when you are approaching your 6th decade. It feels bad enough having to go to research seminars where people bang on about Alzheimer’s, Tau, gamma-secretase, Presenilins and all that depressing stuff.

Anyway, I sat there waiting for the game to start with an odd feeling of sympathy for all my long-ago adult opponents.

And so to the game.

———————————————————–

White: A Elliott Black: D Bowden 19th July 2011

1. e4 e5

2. Nf3 Nf6

Que..? I wasn’t expecting that! Black’s second move introduces Petrov’s Defence, aka ‘The Russian Game’. When Black played this move, I tried to remember if I had ever faced it in a proper game – and I couldn’t remember a single one. Going to my archive later (!) I find I had it played against me once, in a school U-18 match in early 1976. That game continued 3. Ne5: Ne4:? (..d6 is the standard move) 4. Qe2 Ng5?? 5. Nc6+ (oops) and I managed to win with my extra Queen.

Since my opponent in the present game was a keen-looking 13-and-a-bit year old, I suspected he would have read a book, or possibly two, about what should happen after any standard continuation. So I tried to confuse him with:

3. Nc3 Nc6

– and now we have the Four Knight’s Game, which every chess player has played at least once, and which has a reputation for innocuousness.

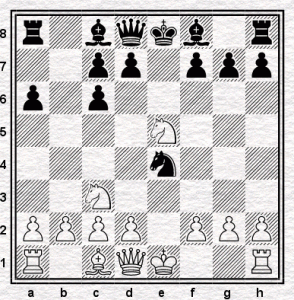

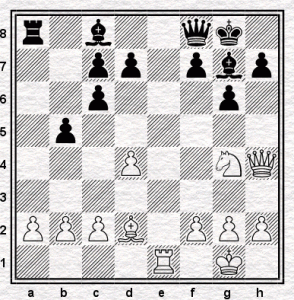

Position after 3...Nc6

When I looked through the archive I found, again, just one game from my playing days featuring the Four Knights, though reached by a different move order. This was one of the earliest games I have recorded, played when I was about the same age as my current opponent. I have had the position more recently in one or two games against the online version of the Shredder chess programme.

Which is another story… because in those computer games I was messing about playing the so-called ‘Halloween Gambit’, which is (in this position) 4. Ne5:?! This piece sacrifice cannot really be sound, but it leads to interesting play if Black tries to hold on to the sacrificed Knight, usually with White trying to checkmate a Black King which is often stuck in the centre.

Anyway – I sat there, wondering if I dared to play the gambit in a sort of serious over the board game. What if I lost? The rest of the team might quite reasonably think I had been taking the piss.

Another thing that spoke against daring the gambit was that all my games in this line with Shredder have followed one particular sub-variation of the Halloween Gambit. This is one of the things about chess computers – give them the same position, especially early in the game, and they will often make precisely the same move. But what if Black were to play something different, and that I’d never seen?

Anyway, after a few minutes vacillating I chickened out, and played the staid:

4. Bb5

His next move surprised me a bit too, especially as he played it almost straight away:

4. ….a6

The question here is whether White can actually win a pawn by Bc6: and then Ne5: The answer is ‘no’, but it looked like it would lead to some sharp play. Since the Four Knights has such a reputation for draw-ishness (notably after 4. …Bb4), I decided to have a go.

5. Bc6: bc:?!

6. Ne5:

– which looks a bit like it wins a pawn – but:

6. …Ne4:

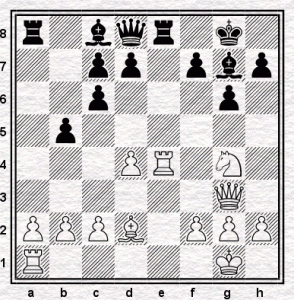

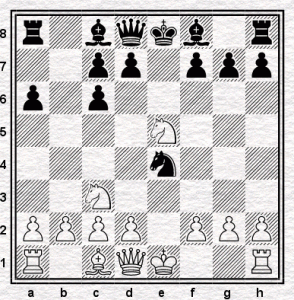

Position after 6... Ne4:

The usual 5th move for Black in this variation is 5 …dc:, so that after 6 Ne5: Ne4: 7. Ne4: …Qd4 wins back the piece, though the variation is supposed to be favourable for White after (say) 8. 0-0 Qe5: 9. Re1 Be6 10. d4

[For instance, a game I found on a Russian chess server, D Borisyuk – M Kotsjubinsky ran:

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bb5 a6 5. Bc6 dc 6. Ne5 Ne4 7. Ne4 Qd4 8. 0-0 Qe5 9. Re1 Be6 10. d4 Qf5 11. Bg5 h6 12. Qd3 Kd7 13. Bh4 Re8 14. c4 Kc8 15. Qc3 Kb8 16. Bg3 Bd7 17. f3 h5 18. h4 Be7 19. Rad1 Qg6 20. Qa5 Bd8 21. Re3 Bc8 22. Rb3 Ka8 23. Bc7 Bh4 24. Qb6 Bd8 25. Bd8 Rd8 26. Nc5 Qc2 27. Rf1 Qc4 28. Rb4 Qc2 29. Nb7 1:0]

The equivalent idea after 5 …bc: 6. Ne5: Ne4: 7 Ne4: is ..Qe7, winning back the Knight. I probably should have played this, since there look to be several good continuations for White, e.g. 8. d4 to follow either ..d6 or …f6 with 9. 0-0 and 10. Bg5, or simply 8. 0-0 Qe5: 9. Re1 Be7 10. d4 and 11 Bg5.

I didn’t know all this, though the variations are pretty obvious. Anyway, for reasons best known to myself – probably the desire the complicate and to keep more minor pieces on – I played something different.

7. Qh5?! Nd6

Forced, as after ..Qe7 8 Ne4: the White N on e5 is protected.

8. d4 g6

9. Qf3 Bg7

10. 0-0 0-0

11. Re1 Nb5

Black’s 11th move came as a complete surprise – I was expecting either ..Re8 or ..Bb7. After the game he told me he had played Nb5 intending to recapture with the c pawn after Nb5:, and only after I played Nb5: did he notice his c-pawn was pinned.

12. Nb5: ab:

13. Bd2

I had quite a long think about where to put the Bishop. I was tempted to play Bf4 to reinforce e5, but that would block the Queen’s attack on the f-pawn. Also on d2 the Bishop might be threatening to go to b4.

By this time, I had used about 40 min of my allotted hour’s thinking time, while my opponent had used less than 20 minutes. Of coures, young players are famous for playing quickly, see above, but when did I get to be so slow?

13. …Qh4?

His first real middle-game error, since it allows the White Rook to reach e4 with gain of time. When you are getting a bit short of time it’s always nice when your opponent plays moves that allow you do something obvious without having to think too much.

14. Re4 Qf6

15. Qg3 Re8

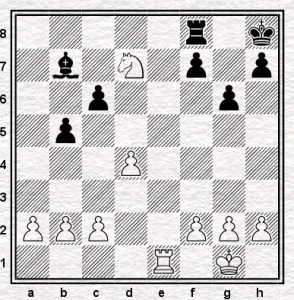

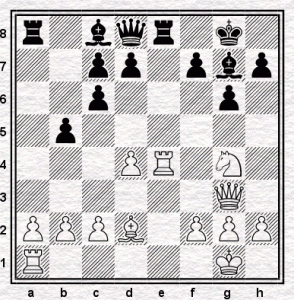

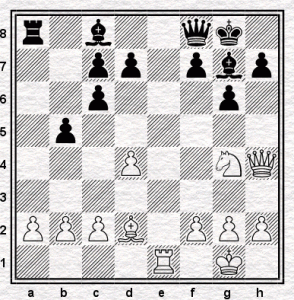

Position after 15... Re8

Obviously White doesn’t want to trade Queens – in an endgame Black’s two Bishops might be quite tasty, and White’s small remaining lead in development likely wouldn’t count for much. Anyway, now I saw a tactical trick to force Black back:

16. Ng4 Qd8

– if 16…Re4: 17. Nf6:+ Bf6: 18. Qf3 and White wins the Bishop too, e.g. 18…Rd4 19. Bc3

And here we reach probably the game’s most critical point.

Position after 16. ...Qd8

The Kibitzers in the room downstairs wanted me to play the Queen offer 17. Qc7:!? here.

Position (variation) after 17. Qc7:

The main idea is obvious – 17 …Qc7: 18. Re8:+ Bf8 19. Bh6 and mate on the back rank to follow – or does it?

Position (variation) after 19. Bh6

I saw this far, but was worried that Black could defend the Bishop with 19… Qd6. Actually, simply trading the pieces there with 20. Rf8:+ Qf8: 21. Bf8: Kf8: would leave White a pawn up in the endgame, but I thought I should be looking for something better. I didn’t notice that Black has what LOOKS like a better defence after 19 Bh6 by playing 19…Bb7, when the White Rook is attacked. What does White do now? 20. Rae1 looks good – threatening 21. Ra8: Ba8: 22. Re8 – but Black can play 20..Qd6, when trading pieces on f8 again gives the same endgame, though probably a bit better for White than before as in this version his Rook is already on the e-file (say after 21. Bf8: Qf8: 22. Rf8:+ K/Rf8:23 a3), or perhaps all the heavy pieces will be traded off.

Of course, one should remember that, as the chess saying goes, it is always easy to sacrifice someone else’s pieces!

Anyway, this all looked quite good when we were analysing it after the game, but a bit later it occurred to me that after:

17 Qc7:!? Qc7: 18. Re8:+ Bf8 19. Bh6 Bb7! 20. Rae1

– Black can play 20…f5! giving his King a much-needed escape square on f7.

So is there a really clear win for White anywhere in these variations after Black accepts the sacrificed Queen? There is, the key being to prevent Black from playing …f5 with a judicious Nf6+.

So:

17 Qc7:!? Qc7: 18. Re8:+ Bf8 19. Bh6 Bb7!

.. and now, instead of 20. Rae1 straight away:

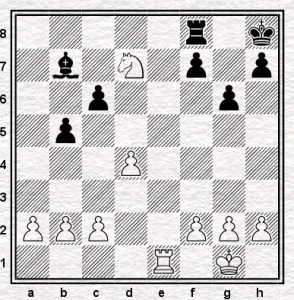

20. Nf6+! Kh8 21. Rae1 (threat: Ra8: and R1e8), when the best Black can do is 21… Qa5! 22. Bf8: Qe1:+ 23.Re1: Rf8: 24. Nd7: and in this version White is two clear pawns ahead and should win without too much problem.

Position (variation) after 24. Nd7:

Of course, there is another snag with the Qc7:! sacrifice:

– which is that Black does not have to accept it. He could decline it various ways, including the simple 17…Rf8, or 17. …Ba6 connecting the heavy pieces on his back rank and avoiding the mate threats that way, or even the slightly wild 17. …f5.

So how much of this did I see over the board? Not that much, I admit. I saw 17. Qc7:, and that there seemed to be a defence against certain bank rank mate with 19 …Qd6… And then I decided not to chance it. Partly this was because I was now down to 15 minutes for my next 14 moves. I decided that if I sat there trying to calculate the variations after 17. Qc7: I was going to lose on time, and played something obvious (though, as it turns out, not that good).

So back to the actual game:

17. Re8:+ Qe8:

18. Re1 Qf8!

The trade of Rooks seemed an obvious way to remove one of Black’s defenders without losing time, but does it help? I had not anticipated 18 …Qf8! – I was expecting …Qd8. 18. …Qf8 puts an extra defender on the h6 square, stopping White from forcing off the Black KB with Nh6+.

19. Qh4

Position after 19. Qh4

Probably not the best. Objectively White should probably take the c-pawn with 19. Qc7:, though it is not clear that White has much. Black can even play 19 …Ra2: after which White probably has to play 20. h4 to avoid mating threats on his back rank. 19. Qh4 does set a cheap trap, though.

19. … Bd4:??

And just when Black’s resourceful defending had got him almost out of the woods, he makes a terrible mistake. 19…d6 was an obvious and good move, keeping the White N out of e5. Although White could force off the Black KB with 20 Nf6+ Bf6: 21. Qf6:, the game would be pretty much level after 21. ..Be6 22. a3, and with the reduced material is not obvious that White could do anything even with the weak Black squares around the Black King. It is even possible that Black can usefully play 19. …f5. One point about this position is that, once White exchanges his N for the Black KB, the two Bishops remaining are of opposite colours, This means that trading off the Qs and Rs would always leave a very drawish ending.

Sadly, the move Black played simply loses the Bishop.

20. Nh6+ Kg7

21 Qd4:+ f6

22 Ng4

– threatening both Bh6+ and Nf6:

22. …h5

– missing the threats and losing the Queen, but he was dead lost anyway. The rest is easy.

23 Bh6+ Kg8

24 Bf8: Kf8:

25. Qf6:+ Kg8

26 Qg6:+

And Black resigns, as it is checkmate next move.

——————————————————————————————-

Postscript: we were looking at the denouement of this game (moves 17-19 and attendant variations) again tonight down at the chess club, and it turns out there are a couple of holes in the above analysis. I shall be interested to see if anyone spots them.

What it does show is just how much there is to find in chess positions and variations, even in positions that are not what you would call super-complicated. Which is, of course, why chess players find the game so enthralling.