I responded to Duncan’s comment somewhat incoherently:

Blah.

UK must invest heavily in scientific research … economic competitive advantage

Blah

I’m not cross at Duncan, not by any means. No, my ire is directed at those public servants, those ‘leading members of both major parties’ who have, apparently, ‘agreed that the UK must invest heavily in scientific research if it is to maintain its economic competitive advantage’.

And this is the whole damnable point, isn’t it? By justifying science–research, what most of my friends do every single day of their undervalued lives–in terms of financial or economic gain we reduce the pursuit of science (ennobled by every lab rat from Aristotle through Newton, Jenner and Heatley right up to and including Hawking) to the level of a whore hawking her tatty wares in Camden telephone boxes to the highest bidder.

Do we really want to make every piece of scientific research done in this country measurable in terms of its impact in pounds and pence–contingent on that impact? Is that what we all–everyone here who says ‘oh, science brings in more than we spend’–want? To have a field on each grant application form that says ‘Enumerate the pecuniary benefit of your proposed research’? To take away money from basic research, the research of Einstein and Rutherford and–why not?–Curry and Rohn, to feed the capacious maw of the Treasury?

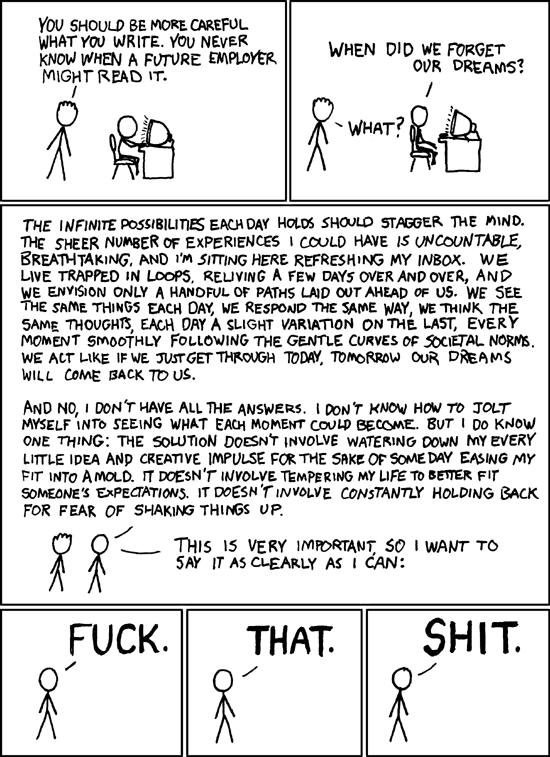

I feel my favourite cartoon coming on.

I feel compelled to step in first (before the stampede) and point out that by comparing me to an Einstein or a Rutherford, you have taken hyperbole to a whole new dimension (in a parallel universe)!

And, only two verys? Not that cross then?

I’m sorry, you’re much much better than either of those two. I should have made that clear.

Every time you post that cartoon makes me very very happy.

So that balances out your very very cross.

\o/

Richard or Stephen (or anyone else who might know): Do most British universities have an Office of Technology Transfer-equivalent, which is, according to Wikipedia “dedicated to identifying research which has potential commercial interest and strategies for how to exploit it”? That’s very much the current business model for research-intensive universities in the US.

And yes, I meant to write business model.

I have not read your post but the cartoons are horrible….

I have read your post and the cartoons are AWESOME.

I won’t blather on about the business models and such. There is a place for it but not for me thank you.

Thanks Benoit by

être en désaccorddisagree with me.One man’s crap is another man’s treasure. In cartoons as in science.

That’s wisdom.

I’ll see your ‘Enumerate the pecuniary benefit of your proposed research’, and raise you a “Social and Economic Benefits to [country deleted]”.

I’ve written lots of these sections, sat on “project commercialization committees”, and interacted at many levels with technology transfer professionals. Yes, there can be economic benefits (oo, social ones too) to research both large- and small-scale. Yes, it plays well with politicians and the public. Do I believe it needs to be in every single discovery research grant? Heck no.

I’d venture that there is a direct correlation between the size of the grant and the likelihood of there being such a ‘pecuniary benefits’ section, but I confess I haven’t bothered to research this in any detail (or at all, really).

Here, I think you need a picture of a kitten:

Oops.

If neither pecuniary benefits (this post), nor tangible benefits to human health (the discussion on Richard’s “On science” post) are the required or desirable outcomes of research funding or salary, then a possible model for rewarding intellectual beauty and creativity is the Macarthur Foundation Fellowship program (the Genius Awards). Description: “the fellowship is not a reward for past accomplishment, but rather an investment in a person’s originality, insight, and potential”. Potential is not defined by pecuniary or healthcare outcomes, either. Private foundation, of course, but the awarded projects are diverse, and for the most part, fascinating and imaginative. Science, arts, humanities, environmental issues, etc. I would be cool with my tax dollars going to such a program. Better that, than some bombs or a border fence.

I’m ambivalent about the cartoon. I like most xkcd comics, but that one, meh. It fits with Richard’s post, though, which is what matters.

@Kristi – yes most UK universities do have a Tech Transfer office. They even have a professional association for such professionals – AURIL .The research funders also have tech transfer offices, so you can have fun if you have joint funding and get some commercially interesting results.

I haven’t read the Royal Society report yet but I have read the Council for Science & Technology report and it’s very clear that research should not be limited to what we think is going to make us money. The point is that we need a broad research base – particularly we need to strengthen physics and we need more engineers – guessing the future is a fool’s game.

If the report criticsed anyone, then I think it was the UK government for not buying the products in the end, this is particularly important for the future for technologies mitigating against climate change where a strong signal from the government that there was a market would be expected to lead to lots of private sector investment in the translation/development stage. For example, I still can’t believe that the contract for high-speed trains went to Hitachi in Japan while the last train makers here was allowed to close. (BTW, the train example wasn’t wasn’t in the report – it’s my own Daily Mail type commentary on the situation because that made me very, very cross).

I would be very surprised if a RS or CST report recommended no basic research at all. I am assuming the RS is reporting on gubmint attitudes.

Yes we need a broad research base for future gain. But did any of us actually go into science for potential economic gain? Hah, there’s another blog post there, isn’t there?

Richard, you are right that all research can’t be justified on return – but there does have to be a mix of pure and applied research, which probably requires some form of quantification.

Einstein is a rather odd comparator. He did his best work while employed as a Patent Officer (third class) in Bern. Is this the sort of research funding you had in mind?

I’m not saying that there shouldn’t be applied research:

Do we really want to make every piece of scientific research done in this country measurable in terms of its impact in pounds and pence?

Einstein is a brilliant example/comparator. He wasn’t even being paid to ‘do science’ at the time.

Thanks, Frank!

How should a government decide who receives funding, and how much, for pure research, then? Or should the government make most or all such decisions? If pecuniary, healthcare, and quality of life implications of research aren’t going to be considered for certain funding programs, what should the criteria be, and who should apply them?

It always seems to come back to money, unfortunately – some types of research are beautifully hypothesis-driven, and very inexpensive to maintain, yet have narrow appeal and no practical implications. Other types of research, for example drug discovery, have defined practical applications, but can be extremely expensive and may not be hypothesis-driven.

I’m not sure what I was thinking, when I decided to go to graduate school. I might have been thinking that I could live in a cabin at a marine station, and study invertebrate or fish embryos for the rest of my life. Certainly I didn’t consider future earning potential, but I won’t deny that I have teh dumb in that arena.

Thanks, Frank!

How should a government decide who receives funding, and how much, for pure research, then? Or should the government make most or all such decisions? If pecuniary, healthcare, and quality of life implications of research aren’t going to be considered for certain funding programs, what should the criteria be, and who should apply them?

It always seems to come back to money, unfortunately – some types of research are beautifully hypothesis-driven, and very inexpensive to maintain, yet have narrow appeal and no practical implications. Other types of research, for example drug discovery, have defined practical applications, but can be extremely expensive and may not be hypothesis-driven.

I’m not sure what I was thinking, when I decided to go to graduate school. I might have been thinking that I could live in a cabin at a marine station, and study invertebrate or fish embryos for the rest of my life. Certainly I didn’t consider future earning potential, but I won’t deny that I have teh dumb in that arena.

Einstein is a good example of one of CST’s proposals that people should be able to move more freely in and out of academia. So if someone has been working in industry for five years but doesn’t have a publication record because the work is confidential how could we rate his/her research? This person probably has important skills that academia could benefit from but are they welcome? Equally I know much much more than I did when I was in the lab – such as how to write a paper – but I’m not sure anyone would welcome me back.

Maybe the government shouldn’t have any say at all in how it spends my money. Suddenly the ‘ask the public what to research’ thingy looks very attractive.

Richard, in theory we elect our governments. Or the people do, or something. Why on earth would you think the public would have a better idea than the people they mandate to think about this full-time, as to what subjects are interesting to them to research?

If we don’t get involved in politics at some level then we have no right to complain. And I don’t mean just go vote, though it’s a start.

I’m afraid that Maria is right, and although I never made good on my attempt to leave an academic setting, although I moved closer to a kind of application at the research hospital I’m at, I’m quite certain that the welcome back is muted at best, which is to our loss.

“Yes, most UK universities do have a Tech Transfer office.”

These offices are not universally popular, as (i) they are now large and expensive to run (with significant numbers of quite highly paid people), and (ii) the question of whether they justify their budget is shrouded in mystery. You can guess what most academics think. See e.g. the second letter here (from an anonymous academic in a well known British research-intensive University) describing the Tech Transfer office with fifty employees. [NB the article that inspired the letter is here]

Anyway, a lot of UK academics tend to the view that large and ascendant Tech Transfer offices do not pay their way, but are “mandated” because that is what UK central Govt wants. Which is where we came in.

Ah, so that would be why the CST report emphasises that the process of commercialisation should be a “pull” from private companies, who know what they want and how to make money from it, rather than a “push” from tech transfer arms of universities. It seems like the partnerships that work actually cut of the tech transfer office.

It isn’t clear to me whether tech transfer offices actually pay their way but they appear to be part of the trappings that all Universities wish to have. I am not clear if the spin-offs from Manchester in recent years would have worked without UMIP (the TT office), I suspect they would have but maybe the existance of an office makes spin-outs more attractive to investors.

CVertainly a number of academics have made money out of spinning stuff out and the University wants its slice of the cake. Income tends to be lumpy with a few successes amid many failures. We are getting more hints that we should be transfering useful knowledge more successfully. That doesn’t mean we should be doing applied research, just that if a useful application becomes evident, then we should look to see if someone would like to develop it further. That doesn’t seem unreasonable to me.

Oh dear, I see pictures in comments are back.

I posted quite an erudite and thoughtful comment on your earlier post on this topic, but unfortunately the system ate it and I got an error message. I had omitted to copy beforehand.

Surely the point is, that whether or not a piece of research may or may not contribute some measurable output to the economy, scientific research taken as a whole contributes far more to a country’s economy (well, a country like Britain) than is put into it by the Government?

I think most researchers are completely uninterested in tech transfer offices, as they are (as has been pointed out) motivated by doing curiosity-led research rather than trying to make a buck out of it. In my experience, some people are motivated by making money, and some people are motivated by curiosity and adventure — and the two don’t often coexist in one person. This is quite a challenge if you happen to have a bean-counting mentality.

No Maxine, I don’t think that is the point at all. The point is that economic benefits are peripheral to the pursuit of science.

Sorry Heather, I was proposing that the public mandating what to research was if not better then at least no worse than the government mandating, not compared with scientists—after all, the government are supposed to represent us but are basically interested only in power and money.

Cynical, moi? Yeah.

One thing that has tended to fall in between Universities and companies in recent years has been solving technical challenges. I’ve written a bit about this before, but maybe I should do a proper post. Anyway, some years ago when a friend and I were trying to work out an “inside-live-cell immunoassay using FRET” method we found that the major funders (and the Univ) were totally unenthusiastic because it wasn’t “scientific hypothesis driven”, while companies (and the Tech Transfer people) all said:

It was very frustrating at the time, and we never did get the project funded, though we came halfway close with one US-based mol bio products company.

So “Method Development” as a subject for funding kind of goes in and out of fashion in the biosciences, but it has definitely been a tough slog in the UK over the last two decades. “But what are you actually trying to discover?” was a question we regularly got asked.

Good point, Austin. Some joined-up thinking is certainly what’s needed.

Someone just emailed me, but is too ashamed to admit to reading the Green Party website. I do sympathize, but this is interesting, so I’m quoting it:

Hmmm…. maybe.

When Robert Wilson, founding direction of the National Accelerator Facility, Fermilab, was asked by the Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy to explain what his facilities contribution to national security was, he responded,

Now, I’m all for poetry. And before I was a taxpayer, living in a bedsit in Elephant and Castle, I totally would have signed up to the dreamy dream of knowledge for knowledge’s sake.

But I’m now trying to buy a house. And I still can’t afford to buy anywhere in the city that I’m confident that, if I were to start a family, my kids wouldn’t become gangsters. This isn’t because of the community, but because of the schools. We’ve have more than a decade of a Labour government — bear with me here, there’s a point coming soon — and by all reports the schools in South London are still roundly abysmal, but for one school that is oversubscribed by 1200%. And if it were a choice between the (hypothetical) Higgs boson and my (hypothetical) going to a real university, I’m not going to choose the boson.

And I’m a physicist!

Science should be about poetry. If only it were as cost-effective as poetry (on a poet’s terms). And many a man in the street thinks we shouldn’t be bankrolling poetry, either (though I agree with Sid Vicious on the man in the street).

But we don’t need to persuade the taxman about poetry. Because the economic argument is so plain, and so awesome. So I think this is an argument we should be making.

Not that we should allow governments to make funding contingent on it. The wrong-headed assumptions that belie the question “what will this specific bit of research do for me?” are assumptions that need to be fought tooth and nail.

But we SHOULD continue to make the argument that science is a game in which everyone is a material (as well as poetic) winner.

Very, very nice comment, Ed.

As an aside, which is the school you’re talking about? My eldest goes to Deptford Green, which has a horrendous rep (and indeed she enjoys getting on the bus and watching kids from other schools scramble away when they see her uniform!) but it’s improved immeasurably in the past few years.

The oversubscribed one is Haberdashers’ Askes’ in New Cross, which seems to the only school in and around Peckham that isn’t struggling.

This is tempered by the fact that I went to one of the worst high schools in the state I grew up in (NSW). That didn’t seem to hurt my life outcomes too seriously. And it taught me how to break into things – which is a handy skill! So I quite like the idea of my kids having a notorious street rep. But I want them to take that street rep to Oxbridge!

Moreover, the primary school I attended, in a different state, in a mountain community just outside of Melbourne, was awesome! We were learning how to solve polynomials in grade 5. And Polly Toynbee regularly cites studies suggesting that primary education is more important than secondary in setting kids’ aspirational goals. So why aren’t more of my taxes going to fixing our schools?

I know the answer is more a combination of Trident, Iraq, and The Bank of Scotland, than the LHC. And, I know all this is middle-class indulgence. But if these neuroses are plaguing me, who should know better, then the rest of voting public surely are.

You misunderstand me, Richard, or maybe (more likely) I did not express myself well. It is a fact that the economic benefits of a strong science research base are greater than the money spent on supporting it. The issues arise when the accountants (et al) try to get scientists or others to be specific crystal-ball gazers.

I sort of disagree with your Richard.

I don’t think you can justifiably spend taxpayers money on our romantic attachment to science as a beautiful and somehow intrinsically usefull endevour.

I think that our scientific leaders should be yelling from the rooftops that science makes money and improves people’s lives materially and measureably. They should also be pointing out that it’s among the best spent tax money you can find. “Look”, they should say “we give not very much money to these extremely highly trained hard working people and look at what they have done for us in 50 years!”. Public funding of science is a really good financial investment and this must be our first argument.

However, every poor bastard slaving over a microscope like you used to should not be required to justify the financial outcomes of their particular research project or estimate how many quality-adjusted life years you will save.

We should be using the whole edifice of science and it’s history to justify all the bricks in the building we choose through peer-review to fund (even the ones that look or turn out to be totally useless). We shouldn’t be using the summation of all the bricks to justify the existance of the edifice.

I agree with your argument when it’s applied in the setting of a project, a program or at a departmental level. But it makes better sense at a macroeconomic level to argue societal utility. And macro is the level at which the spending decisions really get made. Below that and it’s just the scientists cutting up that money.

Or the short version: What Maxine said.

Heh!, my old bean friend Richard, today is my birthday: “Happy birthday to me” (reminds me of Cath).

Every day more older and punished.