Earlier this month I hosted a meeting of CHILL. It is a group of independent health libraries which meets three times a year in the premises of one or other of the members. The meetings are an opportunity to share experiences, organize joint activities and to see different libraries. CHILL brings together a diverse range of health libraries and information services so it can be interesting to visit other members. We have been members since the group started in 1997 but have played host only once, so I thought it was time to invite them up to north London again. I also wanted to show off our newly refurbished library space.

I gave a short talk about the current Library service and later on gave a short tour of the Library. Although the Main Library has changed quite a bit recently, with 70% of the shelving removed, it still inspires awe. The sense of space, the subtle art deco features and the fantastic view combine to make it something special. But I wanted more than just “awe” so I put out a display of some items of historical interest from our collections. Because I had only just come back from holiday this was a bit of a rushed job. I looked mainly for items related to certain people and subjects that were particularly relevant to the Institute’s history. I also included some documents that I thought were interesting by reason of their uniqueness or obscurity.

Henry Dale was the first Director of the Institute. The book Adventures in physiology is a collection of 30 of his research papers from 1906 to 1938. The collection was first published in 1953, with a foreword by the great man himself. Dale explains that he made the selection as a balance “between an author’s fancy and a reader’s probable interest” and therefore decided to focus on two main strands: i) the actions of adrenaline and acetylcholine and the transmission of nerve impulses; ii) the actions of histamine and its role in the response of organisms to chemical, immunological or physical assaults. In his foreword Dale also comments on the role that accidental observations played in his career.

With my mind on Dale, I spotted an interesting historical book – The war of the soups and the sparks by Elliot Valenstein. The book “tells the saga of the dispute between the pharmacologists, who had uncovered evidence that nerves communicate by releasing chemicals, and the neurophysiologists, who remained committed to electrical explanations”. Dale was one of the leading protagonists in this saga.

With my mind on Dale, I spotted an interesting historical book – The war of the soups and the sparks by Elliot Valenstein. The book “tells the saga of the dispute between the pharmacologists, who had uncovered evidence that nerves communicate by releasing chemicals, and the neurophysiologists, who remained committed to electrical explanations”. Dale was one of the leading protagonists in this saga.

We have a large archive of papers from Dale’s time as Director but to sift through these to find something to display would have taken me too long. Instead I hit upon a letter to Dale from William Bragg, under a Royal Society letterhead. Dated 24 Oct 1940, the letter informed him that he had been unanimously proposed for the office of President.

Biological standardisation was another strong interest of Dale’s (see here for a brief history of the field). He was one of the first to see the need for accurate assays of biological substances used therapeutically, and the Division of Biological Standards was established here in 1923. Years later it became a separate institute – NIBSC – but the archives of the first 50-odd years are still held in our collection. I displayed a box from those archives that contained papers relating to the First International Conference on Biological Standardisation, held in Edinburgh in 1923 under the auspices of the League of Nations Health Organisation.

Walter Morley Fletcher was the first Secretary of the Medical Research Committee and did as much as any other man to define the MRC (see my earlier post about him). He was therefore also a key figure in creating NIMR. His pamphlet Medical research: the tree and the fruit is the text of the Fifth annual Norman Lockyer lecture, given in 1929 under the auspices of the British Science Guild. Lockyer founded the Guild in 1905 and it merged with the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1936. Fletcher’s lecture dealt with the history of medical research. He points out that in the three centuries between the accession of Henry VIII and the accession of Queen Victoria whereas great strides were made in anatomy and physiology, there was relatively little progress in practical medicine. It seems that “bridging the valley of death” is not a new problem! Fletcher goes on to describe the rapid progress of scientific knowledge since the accession of Queen Victoria. I fear he gets a little carried away here, saying “As to the art of surgery itself, it is difficult to imagine that it has any further advance to make”. But he later says, speaking of the fight against infectious diseases, “to rest satisfied with our present achievements would be …foolish” and “only the growth of scientific knowledge can bring success”.

After Fletcher’s death a substantial Memorial Fund was collected to be used for a memorial at the new Institute then being built at Mill Hill. In 1936 a memorial ceremony was held, with addresses by George Trevelyan and Frederick Gowland Hopkins. A memorial booklet reprinted these speeches, and included the names of the 500 subscribers to the Memorial Fund, so I included this booklet in my display.

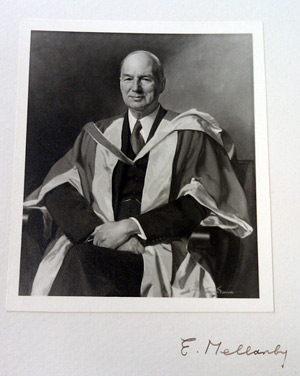

Edward Mellanby was Fletcher’s successor as head of the MRC, serving from 1933-1949. I have it in mind to write more about him one day as he seems like an interesting figure. In my display I included a print of his portrait, and his Royal Society biographical memoir. Photographs and portraits are so important as a way of connecting with figures from the past, making them seem more human than any assemblage of words can. The Royal Society memoirs do a pretty good job though.

I chose a small book by Charles Sherrington (1857-1952) thinking that it was an early popular book about neuroscience, since he was an eminent (Nobel prizewinning) neuroscientist. However, on closer inspection I discovered that Life’s unfolding (1943), part of the Thinker’s Library, is a work of philosophy. The book comprises three chapters of a slightly earlier work called Man on his nature and harks back to the writings of a 16th century physician-philosopher, Jean Fernel. See this editorial for a brief description of the book. I rather like the series title Thinker’s Library. The ever-reliable Wikipedia has a complete listing of titles in the series.

Still in philosophical vein I moved on to Peter Medawar – possibly NIMR’s most charismatic Director and one of the most influential. He was a brilliant thinker and writer about science and the philosophy of science. I selected his short book The Limits of Science (1984). In the preface he explains that he purposely made it a short book because “I have long thought that nearly all books are much too long” and “As a student … I was nearly put off philosophy altogether by the extreme length, leaden prose and general air of joyless learning”. This book is anything but joyless – as you read you feel that someone is talking to you, so straightforward and direct is his style (see review).

Another philosophical book fell into my hands as I prowled the shelves, this one by Harold Himsworth: Scientific knowledge and philosophic thought (1986). It is also a short book and, though it does not have the light touch of Medawar’s style, is quite readable (see review). Himsworth took over from Edward Mellanby as chief of the MRC, serving from 1949-1968, and steering it through a period when biomedical research began a great expansion. The book has a foreword by James Watson, who was of course at the MRC Cambridge laboratory in 1953 when he and Crick published their famous paper on the structure of DNA.

As we are preparing for the centenary of the Medical Research Council in 2013, I was interested to find a special issue that the British Medical Journal put out in 1963 to celebrate the MRC silver jubilee. It included a brief history of the MRC by Landsborough Thomson, a look at the past 50 years of medical research by Henry Dale, a look at the future by George Pickering, and a lovely selection of photographs of some of the key figures in the MRC’s first 50 years. But the thing that most struck me about the issue is … the adverts! I don’t know why but they really convey a sense of 1963.

The MRC was born out of a desire to conquer tuberculosis. Infectious disease more broadly has been a major strand of research at the Institute since its earliest days. Influenza has a special association with the Institute – the WHO Influenza Centre is hosted here and the virus was first isolated here, using ferrets. We have a copy of a cartoon entitled Yoicks and tally ho! which portrays a rather fanciful depiction of a flu virus being hunted by ferrets hotly pursued by a collection of M.D.s on horseback.

Another big research effort was into the common cold. The Common Cold Unit was initially a part of the Institute, under David Tyrrell’s leadership. When it closed down most of their archive came to us. There are boxes and boxes containing the results of different trials, but there are also scrapbooks that contain letters from trial volunteers, photographs and ephemera. I selected to display the scrapbook dated 1981-3.

Tropical diseases were important research subjects from the earliest years of the Institute. I picked out a copy of Ronald Ross’ classic book Malarial fever (1902) and a report on Malaria in the Andamans (1912), one of a series called Scientific Memoirs by Officers of the Medical and Sanitary Departments of the Government of India.

Historians of science start to salivate when they see our report collection. We have an impressive range of early 20th century medical research reports from around the world. I chose some suitably exotic reports:

- Annual Report of the Medical laboratory, Dar es Salaam (1926)

- Bulletins of the Institute for Medical research, Federated Malay States (1927-9)

- Medical Research In The Colonies (1928-30)

We also have a set of the British Intelligence Objectives Sub-committee (BIOS) reports. These were essentially the result of a plunder by the Allies of intellectual property from German industry following World War 2.

The MRC was once a notable publisher in its own right. As well as its own Annual Reports, which contain wonderfully detailed summaries of biomedical research news and very informative overviews of particular fields, it published the Special Report Series. This series was commonly known as the ‘green reports’ due to the colour of the covers of the reports. Special Reports were issued when it was wanted to disseminate research results through an official distribution, e.g. during the First World War several Special Reports dealt with medical topics relating to the war effort. Later they were used for research results that were too long to fit into a journal article. Between 1915 and 1971, when they ceased to be published, 310 reports were issued. I displayed the first volume of our bound set, containing reports nos. 1-10 which were issued between 1915 and 1918. These covered topics including the incidence of Phthisis, meningitis, dysentery, heart disease, atropine, and infant mortality. A more grisly report series was MRC statistical reports on war wounds (1918-20). This emphasises again how much of the very early activity of the MRC was devoted to supporting the war effort. I hope to return to the subject of MRC as a publisher in a later post.

When weeding our books last year I noticed several titles from a monograph series published by the Rockefeller Institute. NIMR was modelled on the Rockefeller, which had been founded just a few years before, and it was interesting to see this series in our collection. I displayed a couple of early titles: Tumors of animals (1910) and Botulism (1918).

However interesting the reports and monographs are, though, they are not unique. Somebody, somewhere has probably got a copy of most of the published items that the Library holds. The archive holdings, on the other hand, are unique. The information about our past scientists is a bit variable, but can be fascinating. When you open a file that you know has not been looked at in 50 years, you really feel like an explorer and I can see why people get hooked on historical research. I have previously written about parasitologist Frank Hawking so I displayed his file. He was at the Institute from 1940-1970. The other file I displayed was that of Major George Dunkin, who was here rather earlier. He was a veterinarian who worked with Patrick Laidlaw in the 1920s and 1930s on canine distemper virus.

This was not intended as a full guided tour to the collection, more of a drunken pubcrawl through it, to show something of its nature and take a few sips of history. I wish I had a better knowledge of the collection, but there just isn’t time. We hope to do some work on assessing the importance of the collection over the next couple of years.

And what a wonderful “pub crawl” (as you call it) it is. Thanks for that, Frank.

That “Yoicks! And Tally Ho!!” cartoon is priceless. 😀

Thanks Richard. I have a feeling that the cartoon was featured in Punch or a similar humorous magazine.