On balance, I prefer laughing to crying but I am not afraid to let my tears flow. Powerful drama can do it, so can stirring music. I may cry when I recall events or times in my life when I have been sad. I can cry when I read about or watch representations of human cruelty. These things are all likely to give my tear ducts a workout. I cried when I read Schindler’s List. I cried at the end of the film Life is beautiful. I cried the first time I saw the ballet Romeo and Juliet, at the tragic denouement of the story intensified by the emotion of the music.

As a performer I struggle to contain the emotional impact I feel when I am singing music. I need to experience the emotion to help me put across the feeling in the music, but too much emotional reaction can interfere with my ability to control my voice. My choir’s next concert is a case in point. It’s a double bill featuring Michael Tippett’s A Child of our Time and a new piece of music written by James McCarthy about an extraordinary young woman whose story has just taken another extraordinary twist. Both pieces use music to tell true stories about awful events, and to point up strong messages for the world.

A few weeks ago my niece left home to start her university career in Bristol, the city where I started my own student life 38 years ago. This stirred up recollections of my time there – the feelings of terrific excitement (the freedom of life away from home!) and terror (the intellectual challenges of education). There were so many new things all happening at once. I tackled them with enthusiasm if not always success. Maths assignments were tough going, but on the home front I did carry out several successful proofs that throwing together lentils, herbs and spices into a saucepan was not a guarantee of creating something edible.

A Child of Our Time

Another challenge back then was my first encounter with Child of our Time. The Bristol University Choral Society, under the baton of Raymond Warren, rehearsed it for many weeks and performed it in concert in the spring of 1977. Prof Warren introduced us to Tippett’s dissonant and luxuriant harmonies, the expressionist pain of his storytelling and the warmth of his arrangements of the traditional spirituals that are interspersed throughout the work.

It tells the story of Herschel Grynszpan, a 17 year old Polish Jewish refugee who in November 1938 shot and killed an official in the German Embassy in Paris. It is a story of anti-semitic prejudice, oppression and exile. The story is tragic in itself but the events that followed the shooting defy description. The assassination “provided the Nazis with the pretext for the Kristallnacht, the antisemitic pogrom of 9-10 November 1938”. I visited Berlin last year, 75 years after Kristallnacht, and saw exhibitions and memorials all over the city. At first I didn’t realise what the memorial panels were – they had a name, a photo, birth and death dates and a brief life story. So many people, such a variety of interesting stories. As I read the stories the link between them became clear. All those people were murdered, executed, or disappeared.

This is the pain portrayed in Tippett’s piece – it is not just about one Polish boy. Composed between 1939 and 1941, it transcends his individual story to deliver a powerful message about all of us, and the evil that can happen if prejudice gains a hold.

Tippett wrote his own libretto. At the heart of the piece is a drama. He tells the bare facts of the story: how the 17 year old boy, worried about his mother back home in Poland and frustrated by official bureaucracy and prejudice, shoots and kills the official. The text is by turns narrative and poetic. We see into the mind of the boy and his family; we hear the antisemitic hatred of the people and the fears of those who are oppressed. Tippett also gives space for wider reflections, and this is where the spirituals come in.

The first words we sing give a clue to what is coming:

The world turns on its dark side. It is winter.

A little later the chorus asks:

Is evil then good? Is reason untrue?

One of the longest choruses us aptly titled “The Terror”. It is terrifying for the choir to sing, with ugly jagged phrases and harsh violent words:

Burn down their houses. Beat in their heads. Break them in pieces on the wheel.

At the end of singing that chorus you feel disgusted with yourself. The storytelling ends, focusing on the boy:

He too is outcast, his manhood broken in the clash of powers.

But Tippett was an optimist. These words are followed by an instrumental evocation of spring, which leads into the powerful extended final chorus:

Here is no final grieving, but an abiding hope … It is spring.

In rehearsal this week our conductor, David Temple, pointed out how extraordinary it was for someone in 1941 to write such positive words and music. The soloists introduce the themes one by one, then the chorus pick them up and elaborate a little. The soloists return to sing an extended rhapsody leading to a musical singularity – a moment of infinite emotion that seems to last forever. The mood relaxes and the music eases into ‘Deep River’, the final spiritual which closes the whole piece in calm.

Back in 1976/77 when I was learning this music for the first time Raymond Warren did a great job of motivating his singers. While the spirituals are a joy to sing, and there are rapturous choruses, some of the other choruses might be described as squeaky gate music. (Richard Witts summarised Tippett’s style as ‘wild, thorny, splashy and opulent’). It was hard work and at first unrewarding. Prof Warren had started a correspondence with Tippett about our forthcoming performance and every few weeks he would read out the latest postcard he had received from the great man, including an assurance that Tippett would attend the concert. This was quite exciting.

Even better, my parents came down for the weekend to hear the concert. I couldn’t imagine what they would make of it. Their musical tastes were fairly conservative, as far as I knew, but they surprised me by expressing great enthusiasm for the work. They had lived through the war as young adults- my father in the North African campaign and my mother back in London. The horrors of the time were real for them and Tippett’s depiction of war and inhumanity bore into them in a way I could only guess at.

Malala

The other piece of music in our concert will be the first performance of Malala, by James McCarthy. It tells the story of Malala Yousafzai, the girl from the Swat valley in Pakistan who was shot in the head for insisting that all girls should have the right to go to school. This is another shocking story, with a message for humankind. The text was specially written by Bina Shah. James McCarthy wrote on his blog:

An educated mind tends to be inquisitive, doubtful, questioning, innovative, logical, playful and creative. … An educated mind, because it is questioning and doubtful, is less susceptible to brainwashing by extremists and it cannot easily be radicalised with promises of an eternal bliss in an afterlife. As George Washington put it (in a line that Bina Shah quotes in the libretto), ‘education is the key to open the golden doors of freedom.’

James McCarthy talks about the piece in this video, which also features interviews with Bina Shah and David Temple.

If you haven’t read about Malala or seen her speak then take a look at this video of her addressing the United Nations. She is admirable: articulate and determined; calm and non-vengeful.

The text we sing in Malala describes Pakistan as

a land of ice-capped mountains and moonlit glaciers .. [with] forests of fruit trees, mulberry, pear, apricot

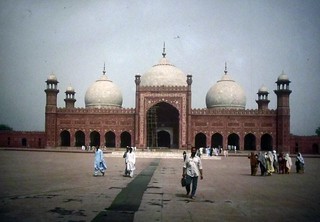

Malala is from Swat in Pakistan, and these words put me in mind of a trip to Pakistan I made in 2000. I visited cities, including Lahore which I loved (beautiful mosque), and the mountainous northern region of the Hunza valley. In Lahore I visited someone I had previously worked with. He was a pious Muslim, with a family of six daughters of whom he was inordinately proud. They all worked hard at school and the eldest was at University already.

Hunza was famous for its apricots and I remember the disgusting-sounding bread and apricot soup which turned out to be delicious, and the delicious-sounding mulberry spirit, which turned out to be highly intoxicating and undrinkable. The most memorable point of my trip was watching sunrise in the mountains, as the sun’s rays kissed each peak in turn, waking it up for a new day.

The story and music of Malala are very different to Child of our Time. Less drama, perhaps, and less poetry, but there is an equal passion. There are moments when I feel emotion welling up in me as the choir tells the story:

Then came the day when they told her that girls could not go to school… Malala dreamed of freedom

Her enemies said: Malala has shamed us. We’ll put a bullet in her head. How dare a girl think that she can defeat us.

At the end of the piece we join forces with a choir of 100 girls voices, to sing:

Malala set the world ablaze. And the world sang back ‘We are all Malala’

If you are free tonight (Tuesday 28 October) then come to the concert at the Barbican. You will be moved by the music and the storytelling. You may see one of the tenors in the second row with glistening eyes, wiping away a tear. That’s me.