Over the past couple of weeks I’ve had cause to celebrate dramatic creativity in various forms, mixed and mingled. I’ve seen one film and two musicals; two with a biographical bent and one with a (fictional) scientific bent.

Hockney

Two weeks back I went to my wonderful local cinema, The Phoenix in East Finchley, to see Hockney as part of an event badged as Hockney Live from LA. The cinema (1910) is a gorgeous artwork in itself, London’s oldest running cinema, and it is always a treat to go there. The programme included a screening of Randall Wright’s new film about David Hockney, followed by an interview with Hockney broadcast live from LA. I’ve mostly enjoyed what I’ve seen of Hockney’s work – The Royal Academy show in 2012 was great – so I expected the film to be a visual feast. I was not disappointed. His life story makes a great tale (boy from Bradford makes good and ends up in LA) and he is an engaging character on screen so the 112 minutes raced past. The Director had access to Hockney’s large personal collection of photos and video material dating back many years, so this film captured a vivid flavour over several decades of the artist’s life. What a gift to the director to have such a rich visual archive at his disposal! Hockney’s paintings often feature his friends; it was interesting to be shown a painting of someone, then an old photo or video of them, followed up with a modern interview of the same person (somewhat older) talking about Hockney.

The live interview with Hockney was slightly disappointing in comparison with the film (it made me appreciate the editing skill of the filmmaker all the more), but it was good to see nevertheless. The film had shown some of Hockney’s photo collages and in the interview Hockney explained how he had taken this further, using digital photography to create ‘reverse perspective’. It was interesting but puzzling. Jonathan Jones gave the film an appreciative review in the Guardian. If you like Hockney’s work I would recommend seeing the film.

Marcos

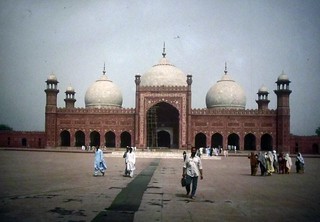

This week I saw Here Lies Love, a musical about Imelda Marcos. This was in the National Theatre’s Dorfman Theatre (previously the Cottesloe), an intimate and flexible space. Some of the audience (including me) were sat in conventional theatre seats along two sides of the space, another large group of audience were stood around downstairs – very much part of the action. There was a stage at each end of the space and mobile stages in the centre of the space. The whole setup had a disco-dancing nightclub vibe (apparently Imelda loved disco). The action took place all around the space, and was slickly done. The show told the story of Imelda’s life – another tale of poor girl makes good – she married the man who was to become President of the Philippines (Ferdinand Marcos). It uses dance and song, but also mixed in a good deal of historical video and audio material, including one shocking scene towards the end. Again the video added an extra dimension to this biographical story.

It is a very fast-paced show, with lively music (by Fatboy Slim) and very strong dramatic and vocal performances. It portrayed the glamorous side of Imelda and Marcos (“Asia’s Jackie and John”) – this is crucial to understanding the love (yes, love, or even adoration) that Marcos followers had for them both, and that some still have for Imelda. One review suggested that the show was too soft in its portrayal of Imelda, but I disagree. Her flaws (ambition, ruthlessness, vanity) were shown clearly. The actions of the Marcos regime were laid bare. The programme note recorded that during the show’s New York run some Marcos sympathisers had walked out in protest. As a spectacle, an entertainment, and a little bit of history, I thought it worked very well; as a political statement it was not quite all there. Michael Billington suggested the subject needs a more complex treatment, which I wouldn’t dispute. If you want to learn a little bit of Filipino history, and like a bit of upbeat music, give it a go.

TRAPP

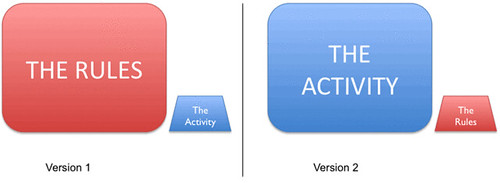

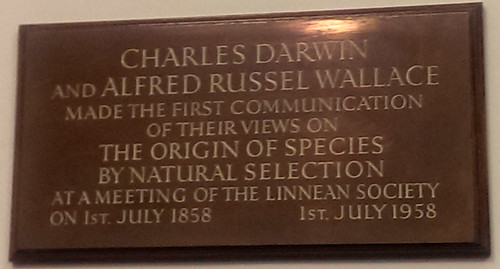

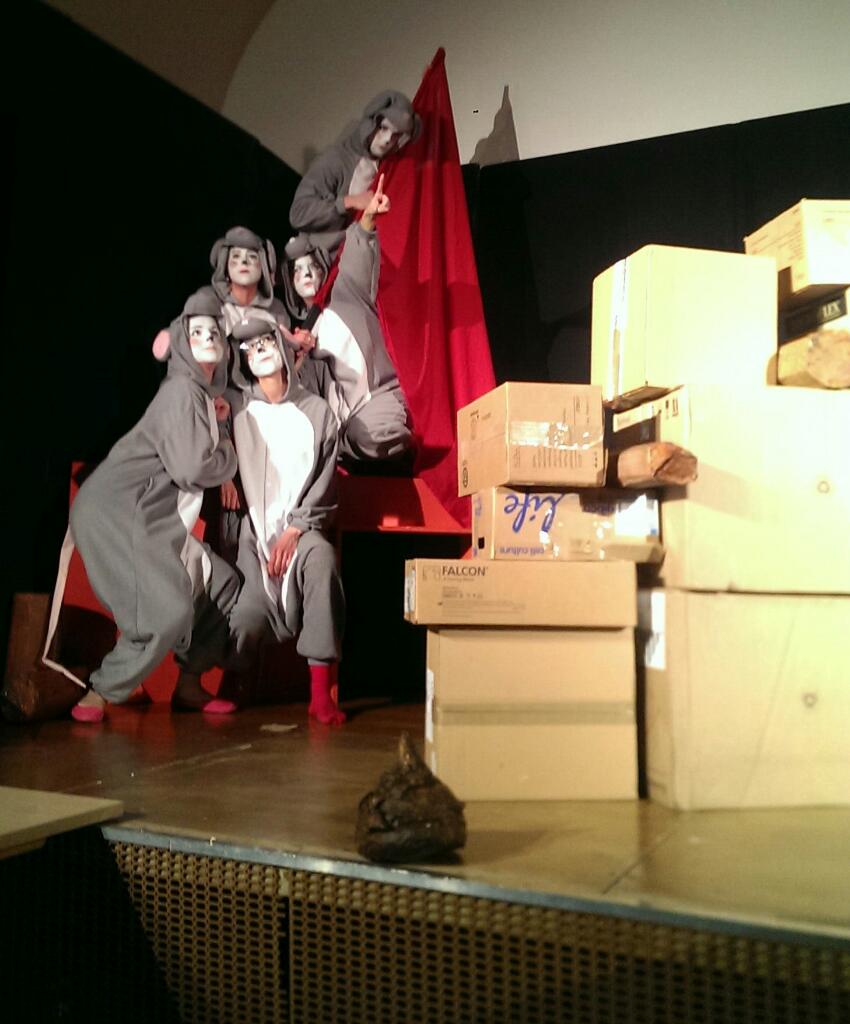

In between these two biographical productions, I attended Mouse TRAPP. This was an amateur production put on in the Institute’s lecture hall by our in-house dramatic society. Whilst the production values were not quite those of the National Theatre, as a dramatic construction it was superb. This musical with a scientific theme was created by one of our postdocs. It was a fictional story about a PhD student – I suppose it could be classified as some kind of Lablit. The ironic posters advertising the show made it plain to see that the writer had a fine sense of humour, so I decided to give it a shot. I was rewarded with a display of drama, humour, pathos and joie de vivre. There were a few in-jokes, and plenty of wry observations on the nature of science and careers in science.

The stars of the show

The story is about a PhD student, Michael, and his journey through his PhD. His lab colleagues and supervisor help get him started, telling him he has to choose a gene to work on. This is the cue for a hilarious song, “Any gene will do” (sung to a familiar tune from Joseph). Michael decides to work on the TRAPP gene, which was supposed to affect intelligence. He generates a strain of mice with TRAPP constitutively expressed – this gives them ‘near-human’ intelligence. Much of the play is about his interactions with these mice, and his affection for them. Naturally the mice can talk, and they are great comic creations. The show was funny, acutely observed, and had vivid characterisation. It was a commentary on lab life and scientific careers, the life of a PhD student, the issue of animals in research, inter-generational tensions, women in science, etc etc. It was relevant, but above all, it was funny!

These three shows of different kinds each left me with a buzz, an admiration for the huge talents of their creators and the creativity displayed. Each of them also had a curious mixture of different elements which is something I love. Truly we are in the age of the mash-up, the magical commingling of different elements to produce a surprising result. Narrative alchemy.