I have been singing with Crouch End Festival Chorus (CEFC) since late 1994 but I have now retired from the choir. The Rachmaninov Vespers on 31 March was my last concert with CEFC as a member. It will be quite a wrench after 28 years singing with CEFC but my voice is telling me it’s time to quit. This will be the first time in my adult life that I have not had a regular choir practice to attend each week.

I’m not giving up singing altogether: I will continue singing in my local church choir most Sundays, and I’ll still sing semi-regularly with a couple of other church choirs. These all entail turning up on a Sunday, rehearsing and then singing the service, so there’s no midweek rehearsal. I will also remain on CEFC books as a guest singer so I will receive invitations to sing with them on some occasions, but I won’t be a committed member.

Looking back

I didn’t do much choral singing as a child but in my later school years we had an enthusiastic head of music (Father Thomas Carroll) and I sang Handel’s Messiah, Haydn’s Nelson Mass and Mozart’s Coronation Mass when I was in the sixth form. This sparked my interest in choirs.

A quick trawl though my memory suggests that in the past 47 years since leaving school I have sung regularly with sixteen different choirs, plus quite a few more that I sang with briefly or sporadically, or joined for one-off performances. Sometimes I sang with two or three different choirs at a time so I had multiple rehearsals to attend every week.

Here are a few highlights of my choral career including music that was special and performance places that were special, choirs and chorus masters that made a significant impact on me, and some treasured experiences.

My first adult choir – Woking

After leaving school I worked for a year, living at home. I joined a local choir – Woking Choral Society, conducted by Nicholas Steinitz. He was the son of Paul Steinitz so had a good musical pedigree. This was my first experience of music making in an adult group. I was only there for a year but I treasure my first introduction to Bach’s St Matthew Passion (glorious) and I remember a luscious concert in Guildford Cathedral where we sang Faure’s Requiem and Rachmaninov’s The Bells. Everything I sang was new and exciting back then.

Getting into church music – Bristol

At Bristol University I sang in the big University choir and we performed Tippett’s A Child of our Time. The music professor who conducted the choir had a correspondence by postcard with Michael Tippett and he read these out at rehearsals to encourage and inspire us. Then we were amazed when Tippett actually turned up at one of our final rehearsals. My parents came to the concert and found it very moving.

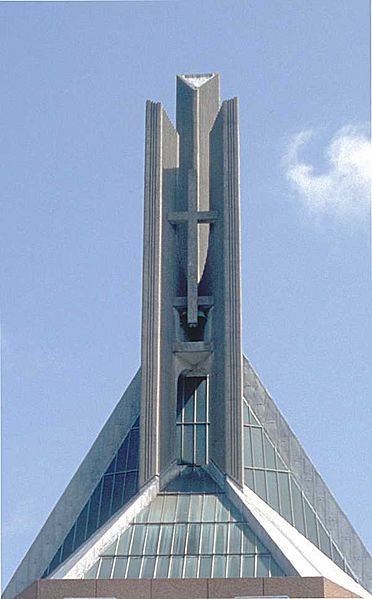

My most formative experience at Bristol though was singing church music. Soon after arriving in Bristol I went along to a service at Clifton Cathedral. It opened in 1973 and I loved the modern concrete architecture. After the service I introduced myself, saying how much I’d enjoyed the choir’s singing. I somehow found I was then invited to sing with the choir.

Clifton Cathedral

Clifton is an RC cathedral but we sang music from Catholic and Anglican choral traditions. The high throughput of music of different styles, from Renaissance to 20th century, was a challenge, especially as it was all new to me. I’m not sure I was much use to the choir at first. I recall Chris saying later that he barely heard me make any sound for the first year I was there! By the end of three years I could sight read pretty well and I had sung a huge amount of music. As well as regular weekly services on a Sunday we sang occasional liturgical performances of some bigger works: Dvorak Mass in D, Durufle Requiem, Monteverdi Vespers, Rachmaninov Vespers (in Chris’s own English translation). I also remember a parish pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral. A chartered train took everyone from Bristol direct to Canterbury and we celebrated Mass in the Cathedral, with the Clifton choir singing. Canterbury Cathedral is a marvellous building, beautiful and full of history. I remember staring up and marvelling at the beauty of the incredibly blue stained glass windows.

I left Bristol with a chemistry degree and some confidence in my singing ability.

More church music – Newcastle

I moved to the other end of the country and studied for a year in Newcastle, to get a PG Diploma in Librarianship. I joined the choir of St John’s, Grainger Street under Geoff Watson’s direction. This is an Anglican church in the Anglo-catholic tradition so it didn’t seem such a big step away from the RC services I was familiar with. There was plenty of familiar music and many unfamiliar hymns. At St John’s I had my first experience of Evensong and of the peculiar magic of singing psalms to Anglican psalm chants.

Another strong memory of St John’s is the friendship I found there. Joining a choir is a shortcut to gaining great friends. After leaving Newcastle I met up with the St John’s people a few more times when they went away to sing the services in a cathedral for a week. We had great times and music in Lichfield, Southwell, Worcester and Chester.

A symphony chorus – London

I moved to London to start working as a Librarian. One day I saw an advert recruiting for the BBC Symphony Chorus (BBC SC) and on impulse I applied and went for an audition. I didn’t really expect to get in but I did. The BBC Chorus was a large symphonic choir, all amateur singers but with the resources of the BBC behind it. The BBC SC was the resident choir for the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Now I was singing with a fully professional orchestra and with leading conductors.

At my first BBC rehearsal, in Feb 1981, I was thrown in at the deep end. We started work on Berlioz’ Romeo and Juliet, in French of course with the choir divided in 16 parts. The second piece we rehearsed was Bartok’s Cantata Profana – in Hungarian and also in up to 16 parts. The Bartok piece includes a ferociously hard fugal section with the subject announced by the tenors on their own. Terrifying! I came to love this piece once I got to know it. Later that same year the Chorus travelled to Frankfurt to sing Britten’s War Requiem in a festival to mark the re-opening of the old Frankfurt Opera House, freshly refurbished as a concert hall. The symbolism of this (British choir, German orchestra, building partly destroyed in the war) was very moving. We were conducted by Eliahu Inbal, an Israeli conductor. He spent some time on rehearsing the chorus to sing incredibly quietly at the magic moments that Britten creates at the beginning and the end of the piece.

Royal Albert Hall

In my years with the BBC SC I sang plenty of choral repertoire, both the standard repertoire and much unusual music. We sang 10-12 concerts a year. The BBC was dedicated to new music and I was happy about this. Working with Krzysztof Penderecki on his St Luke Passion was an extraordinary experience. At first I didn’t know what to make of the score but gradually he explained what we had to do and the powerful music came together. We also joined the BBC Singers in a performance of the very challenging Ligeti Requiem. The BBC Singers often joined our concerts to sing any semi-chorus sections or just to strengthen the sound. They were brilliant. They sang most of the Ligeti on their own but the Chorus sang in a couple of movements. Another highlight was singing in the first UK performance of Tippett’s The Mask of Time at the Proms. This was a long and complex work that took a lot of rehearsal. The BBC SC took part in several of the Prom concerts each year in the lovely Royal Albert Hall, including the Last Night of the Proms which was always a great occasion, like an end of term party.

Back then I must have been full of energy. Not content with all the rehearsals for the BBC concerts I also joined a church choir. I was living a few miles from Greenwich and paid a visit to look around. I saw an LP in a shop window, a recording that St Alfege church choir in Greenwich had made. It looked good – the kind of church music that I’d sung at Clifton and in Newcastle – so I went along to a service the next Sunday. I was impressed – the choir sang Messiaen’s short piece O Sacrum Convivium beautifully. I figured if the choir could cope with Messiaen then it was a choir I’d enjoy being with. So I introduced myself and joined up. It was quite a wild ride – loads of great music and great friends and much jollity (i.e. beer). The musical life in Greenwich was lively, much of it linked to St Alfege church and the choir directors Philip Simms and Steve Dagg. I had the chance to join in various one-off concerts conducted by them. I remember singing in the London premiere of a sacred piece by John Tavener, as part of the Greenwich Festival. Tavener attended our rehearsal on the day of the concert and vividly demonstrated the ecstatic quality of singing that he wanted from the choir. He came over as slightly crazy but very inspirational.

Desert songs – Riyadh

In 1986 I went to work in Saudi, leaving all this marvellous music-making behind. It was not long before I discovered that there was a choral society in Riyadh. It was a bit underground, for expatriates only, and it rehearsed in the basement of a hotel where all the guests were expats. Once more the choir was a good route to friendships in a place that was quite alien in many ways. Musically the Riyadh Choral Society was a world away from the BBC but I sang my first Carmina Burana there – in a large gymnasium accompanied by two pianos, brass and timpani. I also sang the lead male role (Frederick) in the Pirates of Penzance, a rare step for me into the theatrical limelight.

Choirs on tour

I returned to the UK in 1989 and moved to Muswell Hill in north London. I rejoined the BBC SC for a few years but then they switched rehearsal venue from Broadcasting House in central London out to Maida Vale. Coupled with an increase in the number of rehearsals I decided this was too much for me and I left.

During the next year or three I did several one-off concerts with different choirs. Once you were known as a reasonably reliable and competent singer your name got onto choir fixers’ lists and I had the chance to sing in several interesting places. I sang Beethoven 9 in Bremen, in Ghent and at the Edinburgh Festival. After the Edinburgh concert I went along to three different Fringe shows and followed up with a couple of pints in the Festival Club in the early hours. I travelled with the Tallis Chamber Choir to Ireland to sing Patrick Cassidy’s Children of Lir at the Kiltimagh Festival. Kiltimagh is a (very) small town in County Mayo and this was their first festival. We all felt like celebrities walking about the place. It was a small place where everyone knew each other so of course they spotted that we must be some of the festival performers and greeted us like we were stars. I sang Mendelssohn’s Elijah in the Leipzig Gewandhaus with the Nederlandse Vereniging (Dutch Handel Society). Mendelssohn had a strong connection with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra so this performance had a special resonance. I had sung with this Dutch choir a few times previously, including a memorable tour with them to Poland in 1985 to sing Handel’s Theodora. I sang in the premiere of John Tavener’s grand work Apocalypse at the Proms, and later in the Megaron concert hall in Athens – that was one of the best overseas singing trips I made. Apocalypse had some wonderful moments but at three hours was a bit too long. Finally, I sang with Pro Musica two years running: Berlioz Requiem in Le Chatelet in Paris, and Beethoven Missa Solemnis in the Barcelona’s Palau de Musica – a truly beautiful concert hall.

A local choir with ambition

The chorus master for Pro Musica was a certain David Temple. One Friday evening a year or so after the Barcelona concert I was in my local pub when a whole lot of people came in at once, including David Temple. We recognised each other and I learnt that Crouch End Festival Chorus (CEFC) had recently moved their rehearsal venue from Crouch End to a school just round the corner from my flat. I had seen posters for CEFC concerts and they seemed to sing interesting programmes. Now they had started rehearsing almost on my doorstep it would have been rude not to join up. I went to a rehearsal and David auditioned me. I had not prepared anything to sing so he told me to sing Happy Birthday! I passed the audition and became a member of CEFC for the next 28 and a bit years.

For a while I had been a fan of so-called minimalist music but had not sung any of it. My first CEFC concert included Michael Nyman’s Out of the Ruins, a moving and mournful piece written in memory of the victims of the Armenian earthquake. A bit later we sang various pieces by Philip Glass – I especially loved Vessels from his mesmerising film score Koyaanisqatsi. David Bedford’s Twelve Hours of Sunset was also a special piece, finishing in a blaze of glory. Arvo Part’s Credo was a highlight and the choruses from John Adams’ opera Death of Klinghoffer were dramatic and captivating.

Alexandra Palace

The choir also sang in external engagements for concert promoters like Raymond Gubbay and was booked for recording sessions, often of film music. This proved a lucrative activity for the choir and helped it to grow and to perform in more prestigious venues. As CEFC’s reputation grew so the engagements to more interesting. We sang a few times for Ennio Morricone in concerts of his own music that he conducted. More recently we’ve taken part in film screenings with live orchestra and choir. The Lord of the Rings was a memorable one – not least because we sang it five times in one weekend! We’ve also performed Hans Zimmer’s music a few times, with him and his amazing entourage. The technical side of his performances is very impressive.

CEFC used to perform mostly in churches, then used the Barbican quite often but it now has a new home in the theatre at Alexandra Palace. This is ideal as it is local to the area, not too large, and the theatre has an excellent acoustic.

Rock stars

In 2007 CEFC was invited to sing with Ray Davies at the BBC Electric Proms in the Roundhouse, and this started CEFC’s choral rock adventures. The following year we sang again at the Electric Proms, this time with Noel and Liam Gallagher and Oasis. We sang a few more times with Ray and his band, mainly old Kinks songs plus a few newer songs. In June 2010 we went down to Glastonbury and sang with them on the Pyramid stage. That was galactic. Just a few weeks later we were in the Royal Albert Hall on the first night of the Proms to sing Mahler’s 8th Symphony. That combination of two highly contrasting concerts and venues, just a few weeks apart, is uniquely CEFC and was a high point for me.

We sang several times with Noel and his post-Oasis High Flying Birds group on their UK tours. For these gigs with amplified rock bands we had to learn a new way to sing. We each had headphones and were individually miked up. The key thing was to produce a good sound, not to try and compete with the band on volume. For the sound test before every performance we each had to sing a phrase on our own. I recall the terror of singing into the vastness of an empty Manchester Arena and hearing my amplified voice filling the space!

In 2011 we sang with Basement Jaxx and the Metropole Orkest. I’d not encountered this music before but came to love it. The show was very flamboyant – we were all dressed in white shirts and white trousers, with black sunglasses. Some of the soloists had very extravagant and colourful costumes.

The end

Thanks to all the choirmasters I’ve sung for and all the other choir members I’ve sung with. I’ve learnt so much from all of them. I’ve enjoyed all the singing and have many great memories of ravishing music and fun times socialising after the music was over.