As you might have gathered, I’ve got a bit of a thing going for lasers. Seeing as I’m a certified biologist—or biochemist, at least—what better way to celebrate Occam’s first birthday than by writing about a combination of the two?

On one of the many mailing lists to which I’m subscribed, there was a video of what’s possible when one shines coherent light through a droplet of common water. ‘Not much,’ you might think—but truth, as often in these cases, is much, much stranger than fiction.

And a great deal more fun, too.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek made microscopes by making tiny spheres of glass. Small but surprisingly powerful lenses, these spheres would have looked rather like water droplets. They would have had similar properties too: if you’ve ever accidentally spilled water on a document, you’ll be well aware of the magnifying properties of such a drop. The little drops act as powerful lenses—and how powerful is surprising, until you realize that this is more or less how van Leeuwenhoek discovered bacteria.

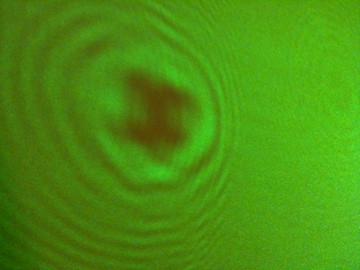

So: take a small glass sphere—or, in this case, a droplet of water—and shine some light through it. You can’t see much unless your light source is, say, a relatively ordinary 50 milliwatt laser. Then something quite remarkable happens.

That thing, looking remarkably like a cell in anaphase projected onto the door, is about 10 cm in diameter. I’m going to assume that it has been diffracted from something that as far as I can measure is a point. The drop—my tiny lens—is a few millimetres across, but I can’t measure the diameter of the entire diffracted light spot very well; so let’s call that 10 cm the ‘opposite’. Or y, if you’re as old school as I am.

I can measure the ‘adjacent’ (‘x‘); and it turns out to be near as damn 2 metres. Recalling my trigonometry I know that y/x = tan θ. So (where’s my calculator?) θ is 2.86°, or close enough.

Which, if I squint a bit at the set-up, doesn’t seem completely insane.

Right?

Now, I know Bragg’s law says you get constructive interference when nλ = 2dsinθ, where d is the crystal lattice distance. But I’m not working with crystals—I’m working with what I want to consider point diffraction, and I’m ignoring interference and whatnot, so I’m going with λ = dsinθ. We shall see that this is not an appropriate approach, but at the time I couldn’t think of a better one. I’d had a couple of gins and tonic, which might explain that—and besides, it was fun. Kids, laser beams and gin don’t mix.

Anyway, if θ is 2.86° and the wavelength of my fricken laser beam is 532 nm (which it is—and I calculated it) then

532×10-9 = d sin(2.86°)

where d is the size of whatever it is that’s doing the diffracting. It’s trivial to solve for d:

d = sin(2.86°) / 532×10-9;

=>

d = 5.32 x 10-7 / 0.05

=>

d = 1.06 x 10-5

which is 10 µm.

Which is pretty darned close to the average size of an animal cell.

Hmm.

While I was working out the maths above I noticed a curious similarity in the sin and tan values. Then I dredged up from the murky recesses of my memory that for small angles, sinθ approximates tanθ.

λ = dsinθ (=> λ/d = sinθ)

and

y/x = tanθ

and sinθ = tanθ

Therefore, substituting for the angle term in son of Bragg,

λ/d = y/x

Solving for d:

d = λ x / y

And now we can easily see what’s wrong with this approach. The sharp-eyed among you will have realized that reciprocal space is, well, reciprocal. In other words, small distances in a lattice diffract to large distances in the real world, and vice versa. Which means, although my attempts at deriving some maths from my little experiment worked (to within an order of magnitude), I was too fixated on diffraction to think in terms of magnification. If you plug some numbers into that last equation you’ll soon see that small objects in the drop should appear extraordinarily large; while large ones shrink to nothingness. That’s diffraction, not magnification.

Which shows you the danger of taking something you’re familiar with and applying it to another system—especially when things coincidentally work out how you might expect them to.

Read on.

What I did, see, was take a scraping from the inside of my cheek, and spread it in some water on a microscope slide. I looked at this under my microscope—I can’t show you a picture of that, because I don’t have a camera attachment. But I did know that the size of the cells I could see was 10–20 µm. Then I took those cells up in my Pasteur pipette and suspended them, in their drop of water, in the path of my laser beam.

And Lo! and behold! We saw cells floating on my spare room cupboard door, about 10 cm in diameter. Which, as derived above, is what you’d expect if you solved some misbegotten derivation of Bragg’s Law for a diffracting unit of 10 µm.

Although the maths is wrong, I’m pretty confident that my laser beam is helping my humble drop of water to a magnification factor of x10,000. The most powerful objective on my microscope is 100x. The objectives are 10x, which gives us x1,000. And, I’ve projected this on my wall.

Now, the resolution of a microscope depends on the numerical aperture (NA) of the lens—the wavelength of the light over twice the NA, in fact. The numerical aperture is defined by n sinθ where n is the refractive index of the medium—1.33 for water—and, hey! There’s that sinθ term again. I’m a little bit stuck now: I want to generalize the magnification factor for this experiment—how the distance from the drop to the wall relates the image to the size of the real things in the drop—but how to determine the focal length is eluding me, and right now I have to get ready to fly to San Diego, so it’ll have to wait until I get back/have more time.

Either way, if one dark night I were to suspend a drop of water in my garden and shine a laser onto the house across the street I could get a magnification of x100,000. But I suspect that not only would my images suffer from some strange diffractive noise effects, I might come to the attention of the authorities for being totally too weird.

Which would be a shame.