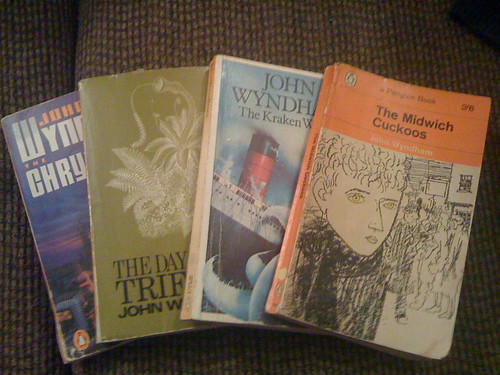

I have a shelf in a bookcase in a bedroom in Yorkshire. It’s labelled “to take to Canada”, and is still stacked with a large number of my favourite books. Every time my parents are getting ready to visit, they ask which ones I’d like this time, and then they stuff as many books as they can into their luggage. This time, I asked for my John Wyndham books.

I love re-reading old favourites. There are some books I’ve read as many as ten times. (I’m the same way with films – it drives my husband crazy). But when deciding which old friend to revisit first, I went with the one I’d read the fewest times – The Midwich Cuckoos.

I imagine that many of my readers are already familiar with this book (also filmed as Village of the Damned); briefly, a sleepy village in the English countryside falls into a day-long sleep, during which every woman of child-bearing age is impregnated. The children develop into identical beings with golden eyes and telepathic abilities, and the villagers (and the government) have to decide how to deal with the invaders.

It’s a cracking story, brilliantly told by John Wyndham. But having not read this book since I was a teenager, there were a few moments that hit me like being slapped in the face with a wet fish. For example:

On a young woman, “scarcely more than a schoolgirl”, seen carrying her newborn baby through the village:

‘Nevertheless, the fact remains that, however the girl takes it, she has been robbed. She has been swept suddenly from childhood into womanhood. I find that saddening. No chance to stretch her wings. She has to miss the age of true poetry’.

‘One would like to agree – but, in point of face, I doubt it,’ said Mr Leebody [the vicar]. ‘Not only are poets, active or passive, rather rare, but it suits more temperaments than our times like to pretend to go straight from dolls to babies’.

On the first reports of the babies’ unusual talents, from their mothers:

‘If,’ said Doctor Willers, heavily, ‘if we take all old wives’ – or young wives’ – tales at face value; if we remember that the majority of feminine tasks are deadly dull, and leave the mind so empty that the most trifling seed that falls there can grow into a riotous tangle, we shall not be surprised by an outlook on life which has the disproportion and the illogical inconsequence of a nightmare, where values are symbolic rather than literal.’

I suppose this kind of language is to be expected of a book first published in 1957, especially when the plot revolves around the subject of pregnancy and motherhood. And I suspect that Wyndham was actually relatively ahead of his time; the main character’s wife is, like the significant others of the main characters in Kraken and Triffids, very sensible and intelligent, if rather two dimensional. And there is this (emphasis mine):

‘It is difficult to appreciate how a woman sees these matters: all I can say is that if I were to be called upon, even in the most propitious circumstances, to bring forth life, the prospect would awe me considerably: had I any reason to suspect that it might be some unexpected form of life, I should probably go quite mad. Most women wouldn’t, of course; they are mentally tougher, but some might, so a convincing dismissal of the possibility will be best’.

However, this context only makes the outdated language slightly easier for a modern woman to read. It’s like listening to a beautiful piece of music, played by an otherwise competent musician who consistently fluffs one note.

I don’t want to deny myself the pleasure of reading great stories by great writers, just because of some outdated ideas and language. But I need more practice at the mental trick I had to employ in order to truly enjoy The Midwich Cuckoos – a state of voluntary cognitive dissonance designed to tune out that one bum note the musician keeps playing.

You’re missing The Trouble With Lichen from your pile, which is on our List (http://www.lablit.com/the_list) of classic lab lit – with a female scientist protag, no less. I haven’t read it yet but it’s on my growing pile. I expect you have, given the title of your blog post. 😉

[shame] I actually haven’t read it [/shame].

I first got into Wyndham when I was about 13. After reading all the books shown in my photo, plus a few others (_Chocky_, Web, and I think there was another one too), I remember checking The Trouble with Lichen out of the local library, but not being able to get into it. I suspect I was too young for the subject matter; this was a frequent problem for me, as my reading age was always at least three or four years above my actual age, but books written at that level weren’t necessarily suitable for me.

It’s on my list 🙂

It doesn’t seem nearly as bad as my recollection of re-visiting CS Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe which is full of the most awful gender stereotyping. In the end I gave up reading it to my kids.

Same era, more or less. I imagine I’d find the same thing if I tried to re-read that series, or any of the Swallows and Amazons books (I seem to remember the girls doing all the cooking, for starters!) For some reason, books set in the more recent past seem to jar more than true “period” pieces such as those by Jane Austen or Charles Dickens, which contain much worse infractions but which I can read much more easily.

It does seem a shame, though – more cracking stories denied! Depending on the age of the kids, I wonder if it would be possible to teach them the context first, and then read the story, pointing out the parts where things have moved on. So they get the lesson as well as the story (says the person with no kids who has no clue if this would work).

I read Peter Pan quite recently, and as well as being surprised by its general weirdness, the portrayal of Wendy (bascially a mother for all the boys) really dated it. Likewise, someone recommended E.A. Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions as a classic piece of imaginative science writing, but I couldn’t get past the gender stereotyping and put it down, despite the interesting ideas. It is a tough one, though – I’ll always love Asterix, and assume some of the less tasteful racial caricatures were done tongue in cheek…

On the subject of Wyndham, I’ve not read a lot but I do remember being terrified by the BBC adaptation of Day of the Triffids. I also remember reading it a few years later, and being shocked when I found out when it was published – it seemed incredibly contemporary, even 40 years on.

I can confirm the stereotypes in Asterix are indeed tongue-in-cheek. Although the Gaul stereotype of the feastin’ an’ fightin’ isn’t far off reality…

The ones that got to me… The Famous Five books by Enid Blyton… I truly loved them as a child/younger one, but when I revisited them later I found that I got very annoyed with that Anne never got less scared… and some other sterotypical things that probably came with the era?

Ah well, maybe that is some of the allure though? That it is not like that today but it could be good stories back in the days, and maybe still now if just a bit of referencing? And I don’t think I would’ve been that bothered if it would’ve been a few more alternative views to “mix it all up”, alas – not so much. The stories about the children being children and loooking for the adult world sort of works still though, I think.

Cath> I do wonder the same thing… maybe it’s more a problem for ‘us’ than for the children? I mean, if you have one book with less stereotypical characters and then one with more stereotypical ones, maybe the children will still get a diverse image? (or I might be in the idealistic mode, once again?… )

Ah, it’s good to see other readers of Enid Blyton and Asterix in this part of the world where most people haven’t heard of either!

I tend to address the issues with reading dated or period works by reading as a writer: focus on the plot development, use of language, and structure of the story. Maybe that’s not the best way to do it, though…

Tom, I seem to remember thinking Peter Pan was pretty weird even when I was a kid. Pirates and fairies just don’t belong in the same story! I will always love Asterix though 🙂

I keep thinking that some of Wyndham’s books would make fantastic films now that the special effects are so good. They’d just have to find some kind of substitute for the cold war paranoia that provides much of the tension in the early stages of most of his books – nefarious activity by big corporations could be an effective substitute for Soviet Russia!

Nicolas, I didn’t realise how much I’d been influenced by the Asterix books until I went to Rome and drove my friend nuts saying “these Romans are crazy!” all the time.

Åsa, I was a huge Enid Blyton fan too! I loved the Famous Five and Mallory Towers books in particular – I read all of them, and I think I got through about one a day when I was in traction for two weeks with a broken arm once. (I always wanted to be George, not Anne, though.) I tried re-reading one of them when I was about 18 (relieving exam-associated stress!), and it was the class stereotypes rather than the gender stereotypes that hit me the hardest at that stage.

I guess the problem with introducing kids to these old books is that by the time they’re old enough to really appreciate the changing context, they might be too old for the actual story! Maybe we’ll just have to skip a generation or two, and have kids in the future re-read these books at a time when they seem as old and dated to them as Dickens and Austen do to us!

Ken, I don’t know if there is one single “best way”. I prefer not to over-analyse fiction while I’m actually reading it (that’s for dessert!), but maybe that’s just me!

Cath> Yes George was my pick… although I was a bit scared sometimes when she was just a little too obtuse 😉 (I was a very good girl. At least sometimes 🙂 )

Maybe… I read Austen as a time document more than anything. I found her books more interesting and ‘better’ once I read up on Austen herself too.

Cath and Åsa– did you ever read the Lone Pine series by Malcolm Saville? I actually liked them better than Enid Blyton (I was a little older when I read them, though).

I see your 1957 progressive and raise you Thomas Hardy (Two on a Tower), which we’re reading for Fiction Lab.

Åsa, I don’t remember George being all that naughty really! Julian was too much of a goody-two-shoes even for me, though.

Ken, no, I’ve never heard of it. Worth dipping into as an adult?

Richard, my one experience with Thomas Hardy was dire. My sister was really into him and persuaded me to read Tess of the d’Urbervilles. What a drag! I hated it. And then I had to re-read half of the damn thing because I couldn’t figure out how she got knocked up (there was one line about brushing against some guy in a lane or something). I’ve never tried any of his other books…

I loved Trouble with lichens – excellent book, although I was only about 12 when I read it. But then I loved Thomas Hardy too – so maybe doesn’t bode well… and the Midwich Cuckoos, and CS Lewis. Maybe I’m just easily pleased…although I hated Enid Blyton.

Just been enjoying all this discussion, and I’d just like to add one thing – when I stay in London I sometimes stay in the Pen Club. This was where Wyndham lived most of his adult life. It’s a kind of boarding house in Bloomsbury. All his meals were cooked for him and he never had a place of his own until he married late in life. The love of his life was a teacher and in those days women teachers had to give up work when they married (which maybe puts a few of his views in context) and she didn’t want to give up teaching because she loved it so much. So they only married when she retired.

After he was married he moved out to the suburbs and got so involved in domesticity that he almost gave up writing altogether. I gleaned all this from a TV documentary. I found it very interesting (as maybe you can tell :-))

Books from the 1950s don’t always age gracefully, I find. Perhaps in another 50 years we’ll like them better.

@Cath: Yes, definitely worth trying Malcolm Saville, at any age.

Hardy was quite difficult in places to r–

but no. Come along to Fiction Lab http://bit.ly/anNZOD and find out for yourself.

Hi Clare! Good to hear from you.

That documentary sounds very interesting – I know next to nothing about the man himself. I’ll have to look it up – any idea of the title / year / makers?

Henry, I’ll make a mental note to re-read it in 2060, should I be alive to do so! By then we’ll no doubt have moved well past the iPad and will have books downloaded directly into our brains.

Ken, another one for my list!

Richard, nice try! I’ll wait for the podcast 🙂