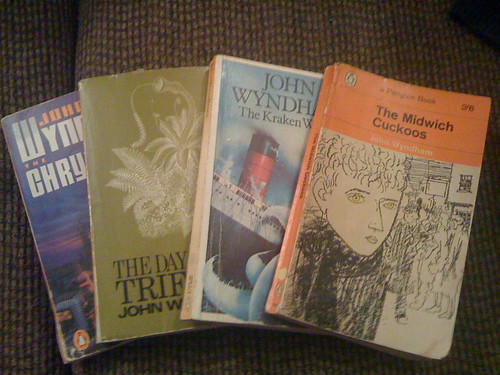

I have a shelf in a bookcase in a bedroom in Yorkshire. It’s labelled “to take to Canada”, and is still stacked with a large number of my favourite books. Every time my parents are getting ready to visit, they ask which ones I’d like this time, and then they stuff as many books as they can into their luggage. This time, I asked for my John Wyndham books.

I love re-reading old favourites. There are some books I’ve read as many as ten times. (I’m the same way with films – it drives my husband crazy). But when deciding which old friend to revisit first, I went with the one I’d read the fewest times – The Midwich Cuckoos.

I imagine that many of my readers are already familiar with this book (also filmed as Village of the Damned); briefly, a sleepy village in the English countryside falls into a day-long sleep, during which every woman of child-bearing age is impregnated. The children develop into identical beings with golden eyes and telepathic abilities, and the villagers (and the government) have to decide how to deal with the invaders.

It’s a cracking story, brilliantly told by John Wyndham. But having not read this book since I was a teenager, there were a few moments that hit me like being slapped in the face with a wet fish. For example:

On a young woman, “scarcely more than a schoolgirl”, seen carrying her newborn baby through the village:

‘Nevertheless, the fact remains that, however the girl takes it, she has been robbed. She has been swept suddenly from childhood into womanhood. I find that saddening. No chance to stretch her wings. She has to miss the age of true poetry’.

‘One would like to agree – but, in point of face, I doubt it,’ said Mr Leebody [the vicar]. ‘Not only are poets, active or passive, rather rare, but it suits more temperaments than our times like to pretend to go straight from dolls to babies’.

On the first reports of the babies’ unusual talents, from their mothers:

‘If,’ said Doctor Willers, heavily, ‘if we take all old wives’ – or young wives’ – tales at face value; if we remember that the majority of feminine tasks are deadly dull, and leave the mind so empty that the most trifling seed that falls there can grow into a riotous tangle, we shall not be surprised by an outlook on life which has the disproportion and the illogical inconsequence of a nightmare, where values are symbolic rather than literal.’

I suppose this kind of language is to be expected of a book first published in 1957, especially when the plot revolves around the subject of pregnancy and motherhood. And I suspect that Wyndham was actually relatively ahead of his time; the main character’s wife is, like the significant others of the main characters in Kraken and Triffids, very sensible and intelligent, if rather two dimensional. And there is this (emphasis mine):

‘It is difficult to appreciate how a woman sees these matters: all I can say is that if I were to be called upon, even in the most propitious circumstances, to bring forth life, the prospect would awe me considerably: had I any reason to suspect that it might be some unexpected form of life, I should probably go quite mad. Most women wouldn’t, of course; they are mentally tougher, but some might, so a convincing dismissal of the possibility will be best’.

However, this context only makes the outdated language slightly easier for a modern woman to read. It’s like listening to a beautiful piece of music, played by an otherwise competent musician who consistently fluffs one note.

I don’t want to deny myself the pleasure of reading great stories by great writers, just because of some outdated ideas and language. But I need more practice at the mental trick I had to employ in order to truly enjoy The Midwich Cuckoos – a state of voluntary cognitive dissonance designed to tune out that one bum note the musician keeps playing.