Recent years have seen a lot of discussion on the blogosphere on gender bias in science. There is no question that awareness is always the first step in heading for a solution.

Do I have an unconscious bias against women in science?

From my personal perspective, I think I have been doing the right things. Two of my three official mentors (M.Sc., Ph.D.) were female. Two-thirds of the students I have mentored were/are female. My most talented and successful student to graduate thus far was female, and she moved very quickly through the ranks to obtain a faculty position and her own independent laboratory.

As I became more established in my own career, I have been doing my best to promote gender equality. One example is that while serving as chair of a study section for scientific funding agency, in a short time I was able to bring the number of male:female reviewers from 70:30 to 50:50.

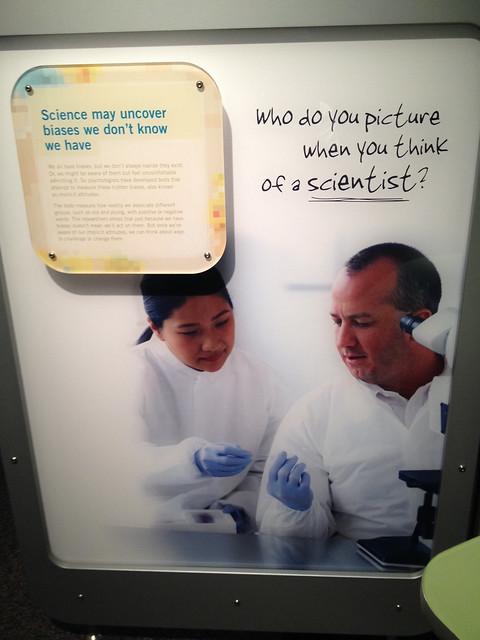

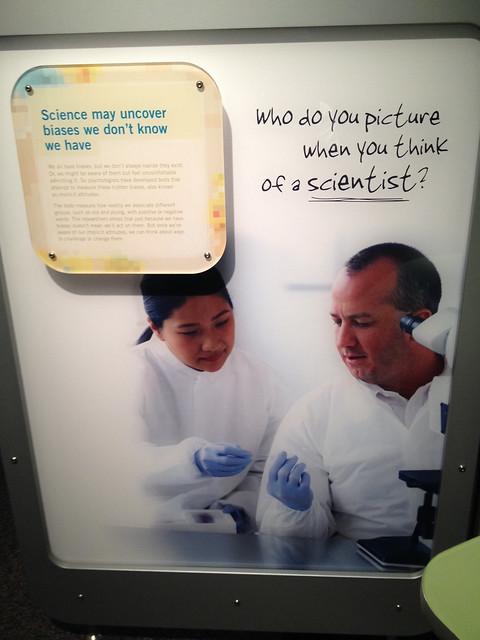

For this reason, I stepped up with interest to the computer terminal at Omaha’s Durham Museum’s “Identity” exhibit to take a test and see whether I have “unconscious biases” regarding the relationship between men, women, sciences and arts.

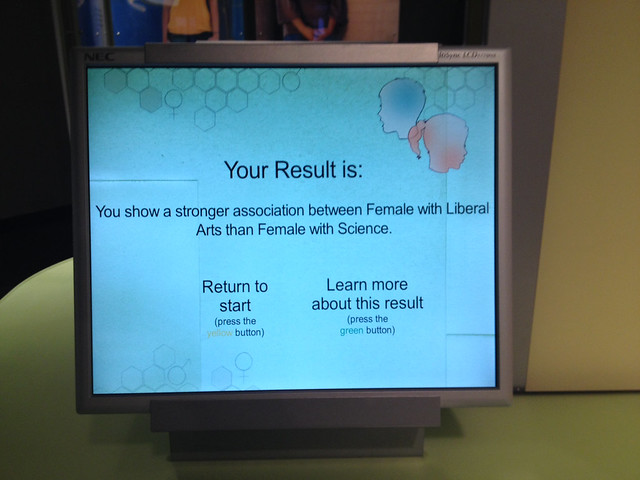

The test was relatively simple: the computer placed the word “Science” on the left and “Arts” on the right, and then had me decide whether to group various words with “Science” or “Arts.” Examples were “History,” “Math,” “Sculpture,” “Physics,” “Astronomy,” “Literature,” etc. etc. The computer then placed “Male” together with “Science” and “Female” together with “Arts” and had me categorize words such as “Father,” “Sister,” “Grandmother,” “Uncle.” I would be timed for how long it would take me to properly categorize the words that cropped up to the left side of the screen (Male and Science) or the right side of the screen (Female and Arts). Then the whole process was reversed with “Male” and “Arts” grouped together on the left and “Female” + “Science” grouped together on the right, and I was again timed.

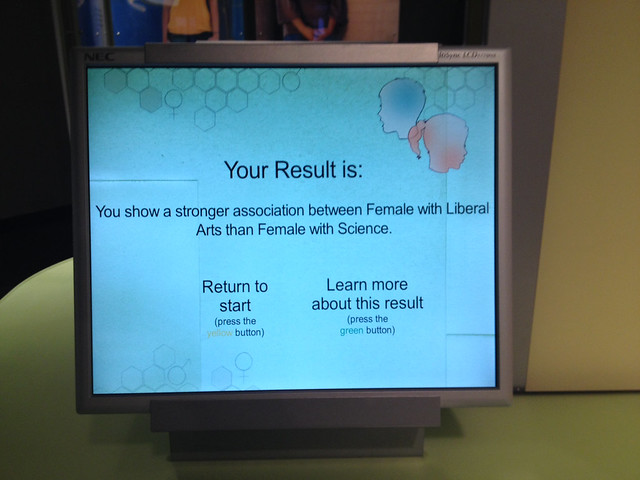

After going through this process in earnest, my results were finally calculated:

According to this study, I am the non-proud owner of an unconscious bias in my perception of women (as being more fitting for liberal arts than science).

While this was supposed to be a fun exhibit (which dealt more with identity of individuals than issues of gender bias), I was somewhat distraught at my diagnosis of being gender biased. I pride myself on my lack of bias, at least conscious bias (what I can control). I even see myself as a male feminist, insofar as pushing for equality between the sexes. In fact, my last novel “A Degree of Betrayal” was described on Twitter by someone I don’t even know as “Possibly a book that every male PI should read.” Am I really that bad?

Let’s assume that this test is accurate in its assessment, although I do have some concerns about whether the time for initial clicking and practicing was properly factored into the timed tallies. But for simplicity, I will accept that I do have an unconscious bias. What does this mean from a practical standpoint?

First, while unconscious biases can teach us about things we were/are unaware of, it’s the conscious biases that are obviously much more damaging. And since, as noted above, I make a conscious attempt to mitigate the situation, perhaps I’m not as bad as this test suggests. But what is the test actually showing?

In thinking about what this test is analyzing, one needs to be cautious in interpretations. It’s no secret that men of my age are much less likely to have a grandmother, mother or aunt who is/was a scientist than a grandfather, father or uncle. This may be a sad truth caused by society’s unfair treatment of women for generations (well, almost forever) – but nonetheless, statistically it is true. So if my responses in placing “Uncle,” “Grandfather,” or “Father” in the category of “Science” were faster than those placing “Aunt,” “Grandmother,” or “Mother” in the “Science” category, does that mean I perceive women as more fitting for the arts than sciences? Or does it merely reflect the overall demographic distribution of men vs. women in these fields, especially when going back a generation or two?

Simplifying things, my concern is whether this elegant computer program is really detecting an unconscious bias that I have toward women in science (or women as scientists), or whether it is merely demonstrating that I know that there are more male scientists than female scientists, especially as the age of the scientists increases.

I am certainly open to criticism and there is always room to improve one’s relationship to under-represented minorities in science (or any field); it’s always good to develop ways to assess conscious and unconscious bias. However, I humbly submit that as scientists, we must carefully interpret the data and ensure that our conclusions are really valid, and that whatever tests are designed to answer a specific question are designed to provide unambiguous conclusions. Unconscious bias against women in science may well be present, but I have serious doubts as to whether this program is capable of differentiating between bias and other factors.